What happens to mining families when there's no mining? The MacPhersons look to a bright future partially shaped by the past

SARAH MacPHERSON had her husband’s evening meal in the oven and the table neatly set ready for his homecoming from the pit when she heard that he was on his way.

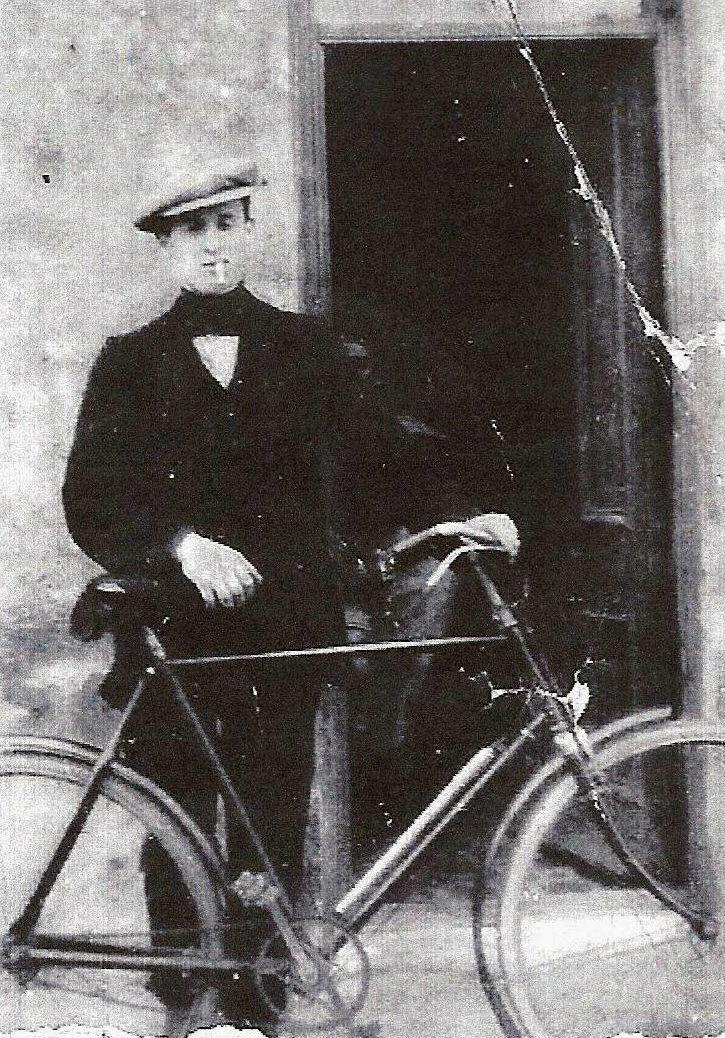

But the energetic 27-year-old Hector that she had kissed off to work in Shotton Colliery that morning was coming back to her in a wheelbarrow dead, killed underground by a fall of stone.

Quickly, she tidied away the knives and forks so that his body, black and bloodied, could be laid out on the table so that she could wash it.

And all the while she had to keep an eye on their first baby, Gordon, who was just four months old.

In decades past, the world of work in County Durham has been cruel. But times change, and now Hector’s descendants are still in the coalfield but, partly inspired by his death, are building new businesses based on health and safety.

The MacPherson family came from Linlithgow, between Edinburgh and Glasgow, in the 1790s, settling first in Darlington. Then for generations, they worked in the coalfield. In fact, theirs is a classic coalfield story, of tough times and hard work, of great pride at what they were achieving but also of always wanting something better for their children.

After Hector was killed on October 19, 1928, Sarah remarried another miner, Matthew Teasdale, and moved to Seaside Lane, Easington Colliery – the main street which runs down to the sea. She set up a laundry, and as soon as Gordon was old enough, he went out with a horse and cart, collecting washing and delivering clean items.

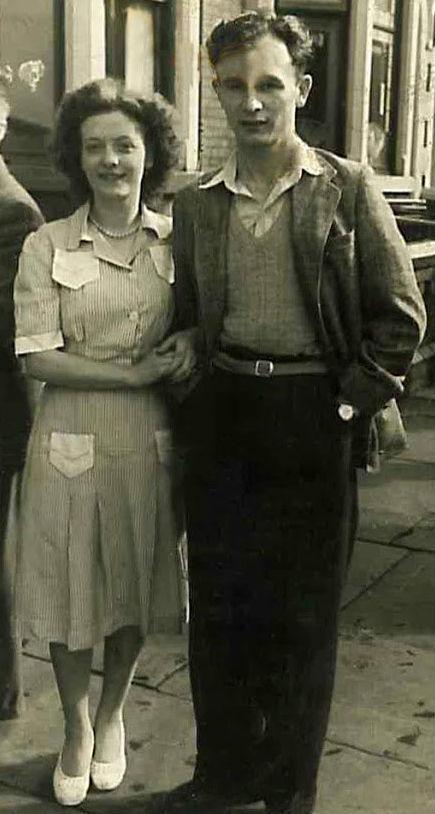

Sarah made Gordon promise never to work in the pit, so he began his career in a moulding factory in Hartlepool. He didn’t take to the stuffy, lifeless atmosphere, and when he returned from national service fighting communists in Burma with the Durham Light Infantry, he married Myrtle and there was little alternative for a family man other than to work at the pit.

Fortuitously, he swapped shifts on May 19, 1951, and was at home in bed when an explosion ripped through his seam. He volunteered to go below and retrieve the bodies of his 85 colleagues who lost their lives.

“He had a tremendous work ethic,” says his son, also Gordon. “He had a seven ton lorry and would go to the beach and collect sea coal and sell that, and he had an allotment where he kept pigs. He’d have a couple of hours sleep and then go to the pit to start his day’s work.”

His drive ensured his children – Gordon and his sister Heather – grew up with the first inside toilet in their terrace in Easington and, unusually, they went on a two week camping holiday on the continent.

“He always said to me ‘you will never go down the pit’. He struggled with a lung condition in the last years of his life; his father had been killed, and Matt, his stepfather, died of pneumoconiosis and emphysema – he was emaciated, skeletal, couldn’t breath towards the end, a terrible way to die.

“So I went to art college in Hartlepool and I liked it, I wanted to be a graphic artist,” says Gordon, whose beautiful photography lines the walls of his home in Cold Hesledon which overlooks the site of Easington colliery and the coaly coast running south to Redcar.

“But I saw my friends making money and I wanted to make money…”

Aged 18 in 1973, Gordon was seduced by the lure of the comparatively good wages to be won underground.

“I was proud to be a miner and to be a miner’s son,” he says. “I loved it, but it was hard and the conditions in the high main were wet, and I had some near misses...”

He remembers how in 1971 16-year-old Stephen Knapper was killed in a coalcrusher – “there were no barriers around things then and they don’t know how he fell in” – and how in 1980, Billy Hogg was crushed against the ceiling by a wagon.

“I had to get him down, using a mell hammer against the steel girder,” he says. “He was the nicest lad you ever meet, and only 19. I still put a wreath on Stevie's grave every Christmas, and that’s what helped me into deputy work because I wanted to do something about safety.”

Becoming one of the youngest deputies in the pit, Gordon took up a management position – and, although he voted for industrial action, he found himself doing maintenance work during the 1980s strike while his mother and sister were running a canteen for the strikers.

“There were times I was on my own six miles out under the sea, 1,300ft down, repairing the pumps,” he says. “I had to go into the area where the 1951 explosion had happened – Duckbills it was called. I went through the sealed door and the stonedust in the air was so thick you could hardly see, but I could make out twisted girders and burnt props and the markings where the bodies had been.

“My parents understood that I had to do what I had to do, and I think the lads understood that if we hadn’t gone in, there would have been no pit for any of them to go back to after the strike.”

Although the men did go back, the colliery’s days were numbered. Gordon’s high main was the first seam to shut as it was inundated by water. He eked out a further 18 months by becoming training officer and was among the 2,000 redundancies when the pit closed in 1993.

“It decimated the community, absolutely decimated it,” he says. “People moved out. Even now, Easington isn’t the same. It was a close knit community, everybody knew everybody. We used to live on Front Street above the 60 Minute Cleaner and Christmas was magical, all the shops were lit up.”

For all the devastation the closure caused, it at least meant that Gordon’s son, a third generation to be called Gordon, didn’t have to be the third generation to juggle his parents’ aspirations with his own desire to earn money. He became the first in his family to go to university, in Huddersfield, to study molecular biology. He then found work in Nottingham, with the forensic science service, and in Sheffield, with the Institute of Cancer Studies.

“Even with the pit closure, I still believed in the North-East,” says Gordon Snr. “I’m proud of where I live, and I wanted Gordon to stay here, but unfortunately he had to go away.”

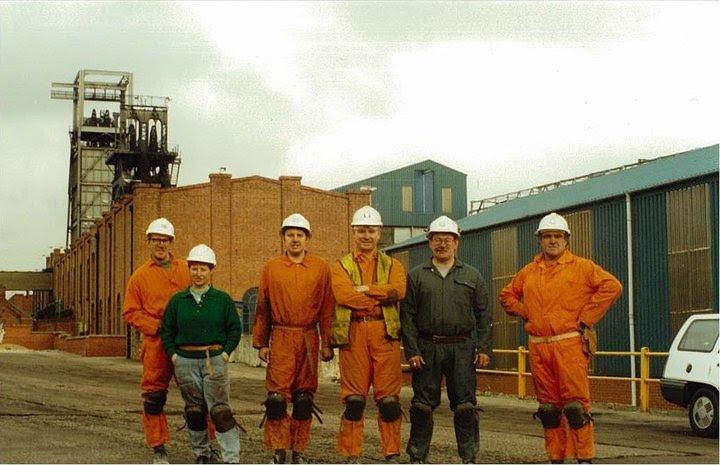

Gordon Snr – redundant from the pit at 39 – was rebuilding. He retrained formally in health and safety, and started working for utility companies, rising to become the H&S officer overseeing the digging of 10 miles of service tunnels for the Olympic Games in London.

But with his daughter, Sarah, becoming increasingly unwell (she died of spina bifida in 2006), he decided to come home and start Seaham Safety Services, running training programmes for construction and manufacturing companies.

“My family history and what I experienced in the pit has put things into perspective,” he says. “Yes, it’s good to have a good wage, but it is no good if you are not around to spend it.”

The starting of the company coincided with Gordon Jnr marrying and thinking about where he might raise his family. So he came home to form a partnership with his father.

“My heart’s here,” he says. “It was hard to be away.”

While out on sites, Gordon Jnr realised that companies were struggling to keep on top of their H&S admin – who is responsible for what, who has completed which courses, who needs to update their knowledge – and so he created a software solution called Moralbox.

“We believe our system will revolutionise the way employers manage their training," he says. “It’s like having a little person on your shoulder saying ‘you’ve got these jobs to action’.”

Based in Seaham overlooking the Marquess of Londonderry’s old coal-exporting harbour, Moralbox has attracted £40,000 investment from the Finance Durham Fund to enable it to take on sales staff.

“We’re on an accelerator programme,” says Gordon Jnr, “and we’re now looking for investment of £400,000. The accelerator tells us not to be blinkered, to think global, so in UK construction, there’s potentially a £59m market and in manufacturing a £46m market for us to aim at, and the US market is ten times as big.”

Now he has his son growing up in the former coalfield to consider. The little chap is nearly two and is called Harrison, although his middle name is, of course, Gordon.

In generations past, Harrison would have left school at 14 and started down the pit. But the world of work has changed – and the MacPherson miners of generations past would surely say for the better.

“I want Harrison to have a really good education, and I’ll support him whatever he wants to do, but I hope that this business I’m trying to get off the ground now will have a position for him, should he want it,” says Gordon Jnr.

“I hope that even if he goes away to university or to start a career that he will move back because there are lots of opportunities here and the future’s very bright.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here