A CAMPAIGN has been launched to save the world’s oldest railway institute which could close within a year.

“The Stute” in Shildon has 1911 in the stonework over the main door of its big, imposing premises in Redworth Road, but its beginnings can be traced to a meeting called by Timothy Hackworth in the cellar of a pub in 1833.

But at the Stute’s annual general meeting last month, the committee was told it is losing £1,000-a-month which would lead to it closing in 2020 – unless there is a change in its fortunes. Immediately a campaign group – SOS: Save Our Stute – was formed, and it holds its first public meeting on Wednesday.

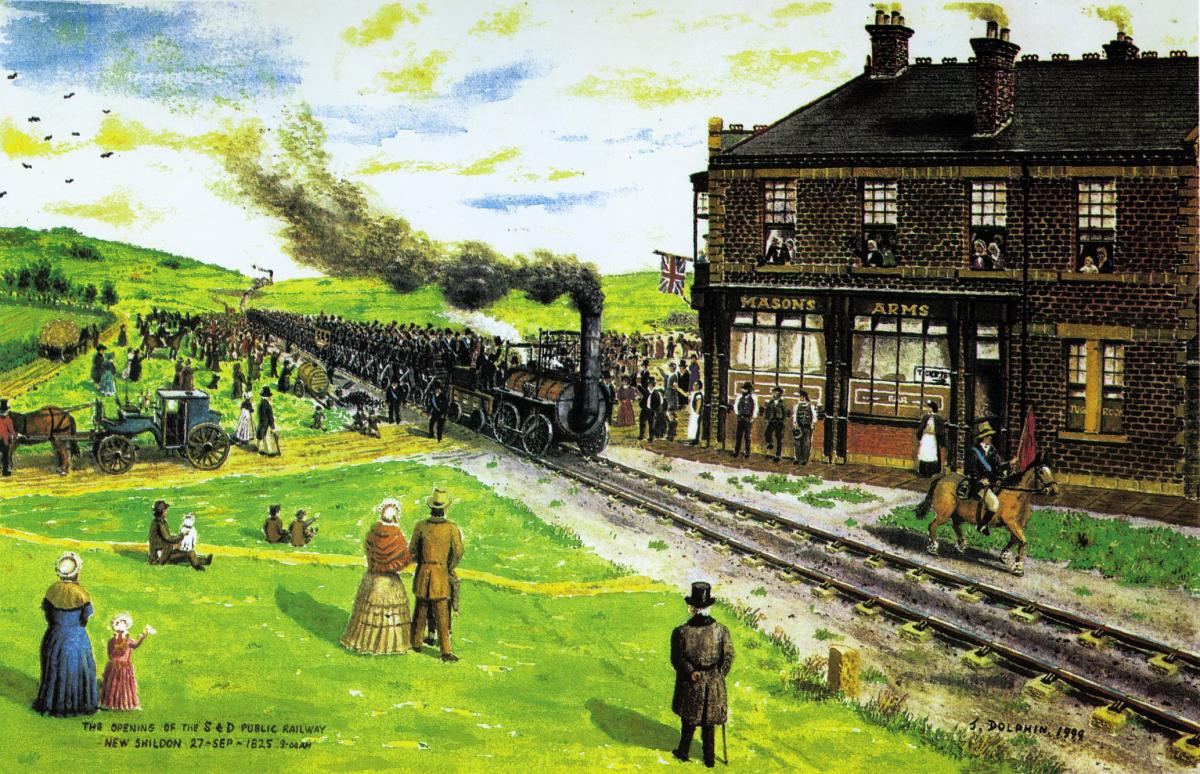

The Stute was formed by Hackworth, the locomotive superintendent for the Stockton & Darlington Railway, as he was concerned that the men who had been attracted to New Shildon – the world’s first railway town – were ill-educated and illiterate. He gathered some like minds from the railway hierarchy among the beer barrels of the Globe’s cellar to consider how to “improve the moral and intellectual condition of the inhabitants”.

In 1833, mechanics’ institutes were all the rage – they provided libraries, lectures and classes so that working men could educate themselves. The first mechanics’ institute in the North-East had opened in 1824, and Memories told last week how in Barnard Castle, Henry Witham had founded the tenth mechanics’ institute in 1832.

However, the institutes elsewhere were all for the general benefit of all working men in a town. Shildon’s was the first that would purely be for the benefit of railwaymen.

But where could the mechanics of New Shildon meet? The only secular building of a suitable size in this new town was the Masons Arms public house, but because it was on the railway line, the S&DR was using it as a station.

So Hackworth arranged for the mechanics to meet in the Wesleyan Methodist church schoolroom which was next door to the Globe – in fact, the landlord of the Globe had knocked a hole in the wall dividing the two properties so he could bang on tin cans and add alternative lyrics when the Wesleyans sung their hymns.

In 1843, the S&DR built a proper station and moved out of the Masons, allowing the mechanics to make a proper home on the first floor – the railway left them a large cupboard for their library, a chandelier was hung from the ceiling and even hat pegs were installed for the working men to hang their caps on. A caretaker was employed on £825-a-year (the Bank of England Inflation Calculator reckons that this chap, a Mr Hamilton, would have been earning more than £100,000 in today’s values so his salary might not be correct).

The New Shildon Railway Institute was a go-ahead institution. As well as its educational activities, it had allotments and advocated a scheme to pipe clean water into the town. It led calls for public gardens to be created for the benefit of its members, and in 1847, a collection of 6s 5d was taken at the end of a lecture entitled The Horrors of American Slavery to help fight those horrors.

The institute held an annual tea, or soiree, to raise funds. This event quickly became the social highlight of Shildon’s year. In 1848, 1,000 people attended the soiree held in one of the railway workshops. Henry Pease, of the S&DR, gave a no doubt eloquent address but perhaps the audience were more interested in the words of Mr Droffmore, a “phrenological lecturer”.

At New Year 1858, a reporter from the Darlington & Stockton Times attended a similar-sized soiree in the Soho Engine Works and was amazed by what he saw. “The room was excellently fitted up with gas, and most gorgeously decked with holly and evergreen, and artificial flowers, and banners, flags etc,” he wrote. “Such a display of artistic skill in weaving wreaths and festoons and devices from earth’s wintry coat of green, and in the delicate manufacturer of artificial flowers, have we rarely beheld, neither have we very often been so highly delighted with the surpassing beauty which it naturally produced.”

The institute was clearly booming, and in 1860, Mr Pease – now the South Durham MP – returned to open its first purpose-built premises in Station Street, near the Welcome building for today’s Locomotion museum. In the Victorian era, the Stute was the centre of the railwaymen’s social world, running sports clubs, hosting classes, organising day trips, agitating for political change.

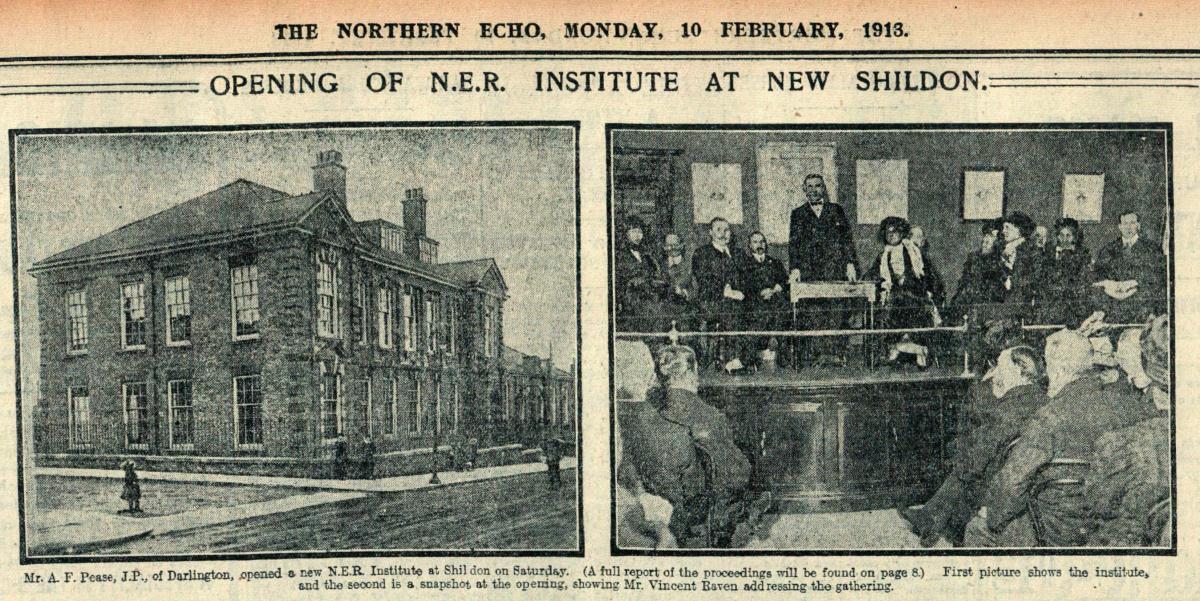

With the Shildon wagonworks continuing to grow, within a couple of generations Station Street was too small and the North Eastern Railway built today’s premises. Although it says “1911” above the door, the building was formally opened on February 8, 1913.

The event was chaired by Vincent Raven, chief mechanical engineer of the NER, who asked RW Worsdell, Shildon works manager, to present a silver gilt key to the principal guest, NER director AF Pease – Sir Arthur, as he later became, was a cousin of Henry Pease and had grown up in the Darlington mansion of Hummersknott.

This Mr Pease performed the opening honours with the key, and said that this was the oldest railway institute in the world. He hoped “the new building would be a very great blessing to the town and that there would be many pleasant social gatherings in it for many years to come”.

Those many years to come may now be coming to an end. When the wagonworks closed on June 30, 1984, with the loss of 2,600 jobs (86 per cent of male manufacturing jobs in Shildon), the railway sold the institute to its members for £1 to use as a social club.

However, meeting 21st Century repair bills at a time when social habits are changing rapidly have thrown the future of the early 19th Century institution into doubt. If it were to go, it would leave a gargantuan hole in Shildon – a physical hole, because it is a landmark building, and a heritage hole because Shildon has so few surviving buildings that connect the community to the birth of the railways.

“It is heartbreaking, but I genuinely believe it has got so much potential,” says town councillor Dave Reynolds, who is one of the people behind the SOS campaign. “First of all, we want to garner public support to ensure it survives in the short term, and then look ahead to the bicentenary of the railways in 2025. We would like to hear people’s ideas for the next stage in the evolution of the railway institute.

“It would be tragic to lose it when such a major anniversary is so close and the eyes of the world will be on the birthplace of the railways.”

The public meeting is on Wednesday (May 22) in the Stute at 7pm.

A new website for the Stute has just been created at

shildonrailway.institute

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel