THE scenes from Notre Dame were terrible: a skeletal ribcage of timber roof supports picked clean by the twisting, spiralling orange flames until the remains powdered to dust and fell into the great burning void where a centuries-old cathedral had stood complete only minutes earlier.

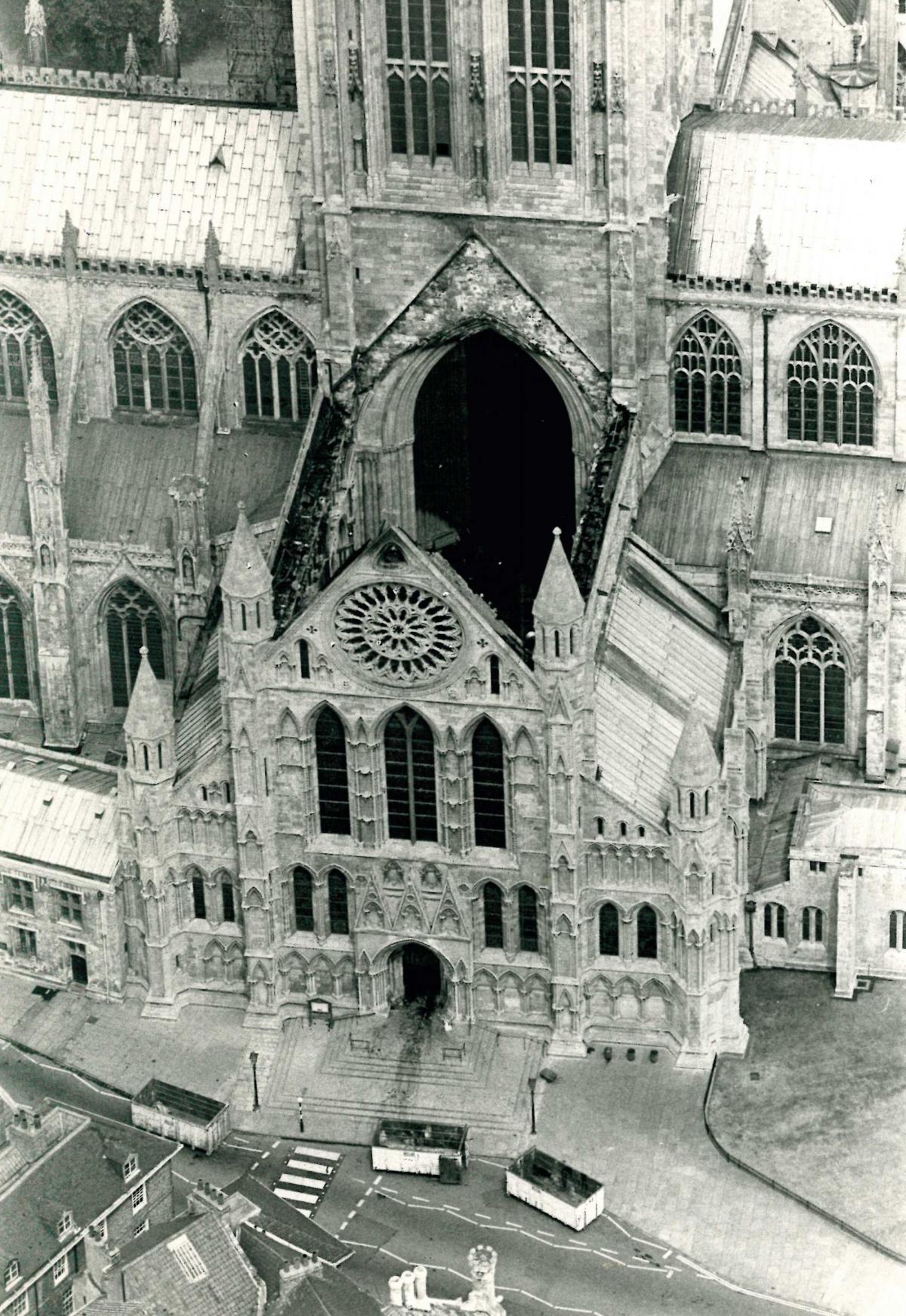

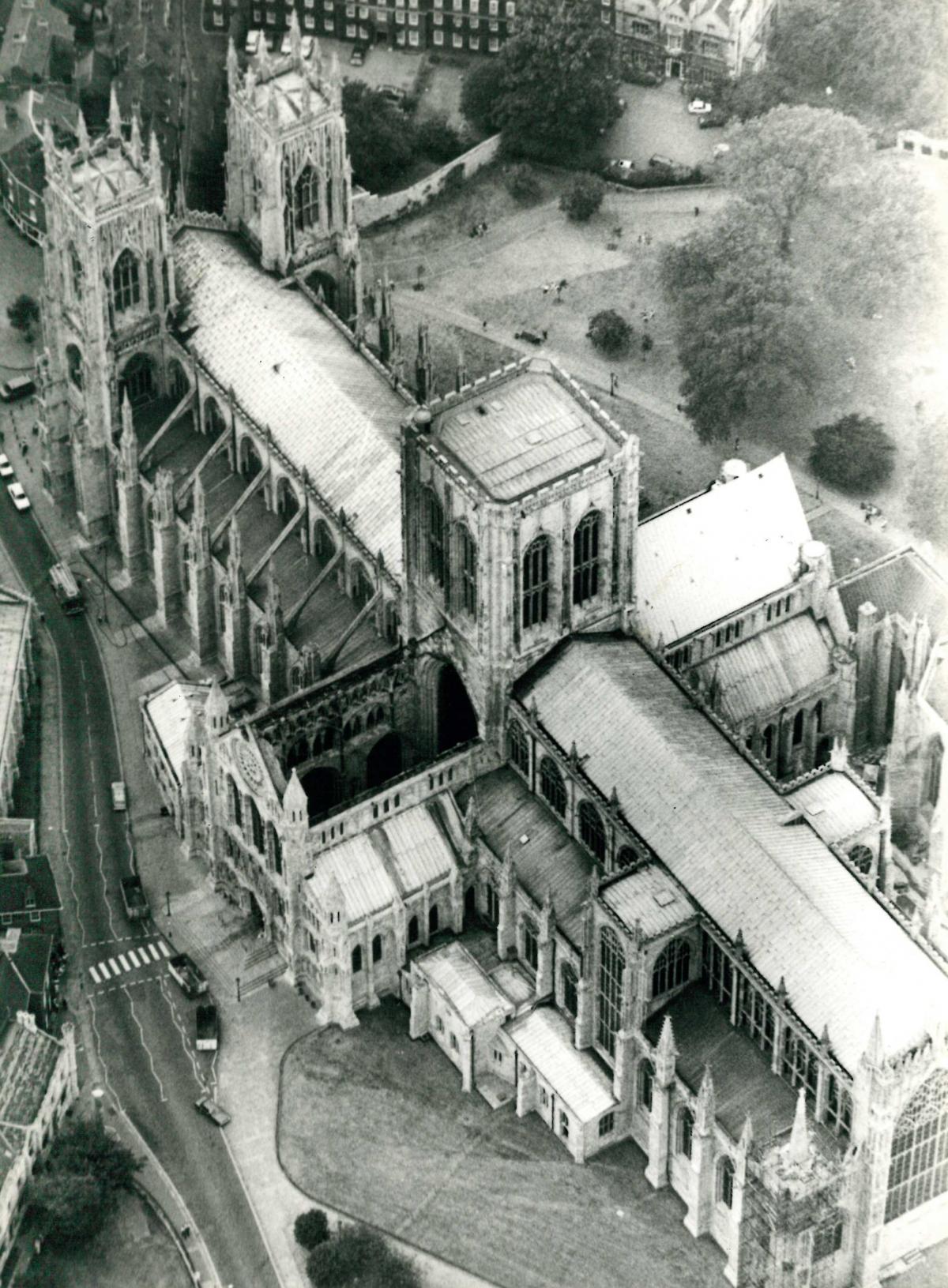

And so it was at York Minster, on July 9, 1984. Lightning struck at about 2.30am and within half an hour, a third of the roof was ablaze, the timbers quickly stripped bare and then deliberately brought down by the firemen’s hoses in a bid to stop the flames spreading.

That wasn’t the first fire at the minster. There was a blaze in the south transept in 1753 which was blamed on workmen’s burning coals; there was a major conflagration in the nave roof in 1840 caused by an unattended candle.

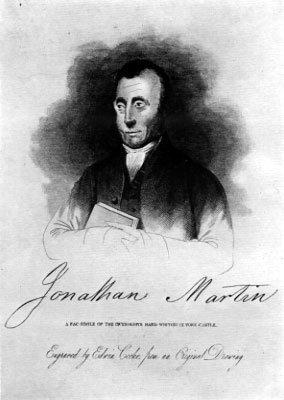

And then, on February 1, 1829, there was the fire deliberately set by Jonathan Martin, a tanner who gave his address as Darlington – a man of great mental distress, who saw terrible visions and heard divine voices and read too much into the flaming imagery of the preachers and ranters.

Martin’s story begins at Haydon Bridge, near Hexham, where he was born in 1782 into a God-fearing, poverty-stricken family. In 1804, he set out to make his name in London, where the streets were paved with gold.

But as soon as he arrived, he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy. For six years, he sailed the seven seas, desperate to desert. During one maritime battle, he suffered a serious blow to the head - possibly a fracture of the skull - which could account for what came later.

He finally escaped, and plotted a course home. He found work in the tannery in the village of Norton, near Stockton, and found happiness: he married and had a son he called Richard.

Martin already thought that thunderstorms were God’s way of expressing His displeasure at Martin’s sins, but things really began to go awry in 1814 when both of his parents died.

His mother returned to him in a vision warning that he would be hanged; soon God was appearing in clouds and in dreams, and Jonathan's behaviour began to deteriorate. He joined the Wesleyan Methodists - "the ranters" - and began a personal crusade against the Church of England whose leaders, he believed, led degenerate and frivolous lives.

"I knew that the clergy were in the habit of going to balls, plays, races, card parties and other sources of amusement; and instead of warning their flocks to flee from the wrath to come, were setting them a most pernicious example," he later wrote.

Early one Sunday morning, he climbed into the pulpit at Norton church and hid, only to pop up when the service was in full swing and begin ranting. He tried the same trick in both Bishop Auckland and South Church, and was "forcibly expelled" by the churchwardens. He became so over-zealous that first the Methodists disowned and then his wife left him.

In 1818, she heard that Dr Edward Legge, Bishop of Oxford, was visiting Stockton and her estranged husband wanted to "try his faith by pretending to shoot him". When she saw that Jonathan had acquired a pistol, she informed the magistrates.

That night, three-year-old Richard had a dream and awoke screaming: "O mamma, the watchman has taken away my daddy."

Next morning, as Richard had foreseen, the constables carried Jonathan off. When asked about his intentions, Jonathan replied: "I did not mean to injure the man (the Bishop) although I considered they (all church leaders) deserved shooting, being all blind leaders of the blind."

He was sent to the asylum in West Auckland - in Fish Hall on East Green, not far from the Grand cinema which featured here last week. He stayed for at least a year and said that the owner, John Smith, showed "great kindness to me". Jonathan was even allowed to work in the fields.

But then Mr Smith departed, leaving the inmates in the care of a 13-year-old servant girl and a drunken assistant. Jonathan was beaten and kept in chains for a fortnight, and his visions intensified.

His workmates in Norton tannery heard of his troubles and arranged for him to be moved to Gateshead asylum, from where he escaped when working in the garden. He made it back to Norton, but was returned to Gateshead and was clamped in irons.

Jonathan acquired a piece of stone and began grinding away the heads of the rivets of his fetters. They snapped, he was free, and he slipped out onto the roof, dropped onto a wall and down onto a dungheap and away.

He regarded his escape as a God-given miracle, although the authorities do not seem to have been too concerned because they let him live unhindered in Darlington for the best part of six years. He resumed his career as a tanner and even began courting the housekeeper of saddler Robert Sturdy in Tubwell Row.

In 1825, he wrote an autobiographical pamphlet called The Life of Jonathan Martin, of Darlington, Tanner. He claimed it was "an account of the extraordinary interpositions of divine providence on his behalf", and for three years, he toured the North of England, flogging his story and earning a living - he sold about 14,000 copies of his pamphlet at one shilling a time.

But the visions were coming back, stronger and stronger. A hymn by Charles Wesley was echoing in his head: "Jesu's love the nations fires, Sets the kingdoms in a blaze."

In late 1828, he settled in York at 60 Aldwark. The dreams became more and more lurid until, in one, "a wonderful thick cloud came from the heavens and rested upon the cathedral". Jonathan knew what he had to do.

After Evensong in York Minister on February 1, 1829, Jonathan hid in a pew until the church emptied and the huge doors clanged shut. He used an old razor to cut up velvet and gold tassels from the Bishop's pews into kindling, which he placed beside pages torn from hymnbooks and the wood of the choir stalls. Then he struck his flint - and fled. He knocked out a window and lowered himself on a bell rope.

The blaze was not discovered until early the next morning, by which time the Minster was well alight. At about noon, the huge oak timbers of the roof crashed down on the choir, molten lead pouring through the void in an apocalyptic scene of destruction.

This collapse, though, enabled the firemen to reach the flames and, after a day of toil, they successfully extinguished them. The 14th Century woodwork was lost, as were the 66 choir stalls, the galleries, "the finest organ in England" and its irreplaceable collection of music, the pulpit and the archbishop's throne.

It did not take long to work out the identity of the arsonist.

The clergy had recently received three letters, warning them that if they did not forsake their bottles of wine, downy beds, roast beef, plum puddings and card playing, "your greet Minstairs and churchis will cum rattling down upon your gilty heads!"

One of the letters was signed JM. Others had an address: 60 Aldwark. When the constables reached the address, the arsonist had fled.

He was found six days later at the home of a relative near Hexham with candlestubs in his greatcoat pockets, plus fragments of stained glass and pieces of crimson velvet and gold tassels that he had taken as mementoes.

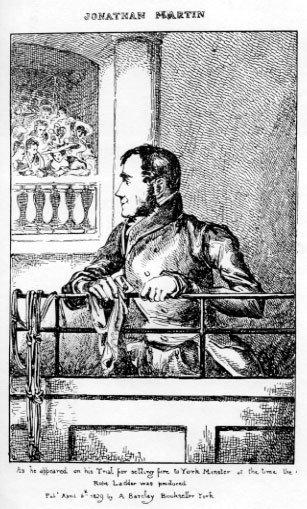

A trial was held in York on March 31. Jonathan's younger brother, John, paid for a prominent barrister to represent him, but it was of little use as the accused agreed with practically every word of the prosecution's case.

It took the jury seven minutes to conclude that he had, as he had admitted, set fire to York Minster, although mercifully they concluded he was "not guilty on the grounds of insanity".

This dismayed the large crowd who had gathered in the hope of a hanging, and Jonathan was carted off to the Criminal Lunatic Asylum, in Lambeth, which was known as Bedlam.

There he died on May 26, 1838, proclaiming to the end: "It was not me. . . but my God did it."

JOHN MARTIN was able to pay for his incendiary brother's defence because he was a critically-acclaimed artist. His paintings showed vast apocalyptic religious scenes – his most famous work, which is in the Laing Gallery in Newcastle, is the Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, is an angry fiery swirl of vivid oranges and reds from which a couple are desperately fleeing.

Such was the awful intensity of his work that the public knew him as "Mad Martin" and he was so famous that a lady in the huge crowd that had gathered to see York Minster burn exclaimed: "What a subject for John Martin to paint!"

She did not know that his brother had sparked the fire.

Jonathan’s son Richard grew into a successful artist, but, on Sunday, August 5, 1838, three months after Jonathan had died in Bedlam, he committed suicide, "cutting his throat with a razor in a dreadful manner".

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel