THIS weekend, one of the North-East’s unique landmarks will be illuminated to commemorate its 50th anniversary – and the 50th anniversary of the debate about whether it is an icon or an eyesore.

The Apollo Pavilion in Peterlee, which will be lit up on Friday and Saturday by the people behind Durham’s Lumiere festival, is an extraordinary structure. At its heart, it is just a bridge across a beck linking two halves of a housing estate, but in its soul it is a brutalist work of concrete art from the space age.

It was designed by one of Britain’s greatest post-war artists, Victor Pasmore, to symbolise the bold hope and the modernist optimism that the new town of Peterlee would provide a new way of living for the people of the declining Durham coalfield.

There were three new towns created in the county after the Second World War: Newton Aycliffe and Peterlee, which were planned in 1947, and Washington, which was begun in 1964. The idea was that as the isolated pit villages died, the former miners would move into the new towns, where they would be surrounded by shops and leisure facilities, and where they would provide a readymade workforce for new industry.

Aycliffe was designed to be a modern take on the Edwardian garden city concept, but Peterlee was going to be a something completely new and special – the flagship of the nation’s 14 post-war new towns.

In 1947, Berthold Lubetkin was appointed chief planner and architect. He was Russian but had been in Britain since 1931, in which time he had proved himself to be a master of concrete, most notably with the gorilla house and penguin pool at London Zoo.

The town for 30,000 inhabitants was to be built on a dramatic plateau overlooking the North Sea, and it was to be named after the 1920s Durham miners’ union leader.

Lewis Silkin, Minister of Housing and Local Government, told Lubetkin: "The country is destitute and coal is our only resource. We want Peterlee to be the international capital of coal mining. Its architecture must be a dramatic expression of the solidarity of all miners.

"The new (nationalised) mining industry will achieve the highest level of productivity. Its workers must be given a town to be proud of.

"We don't want the scattered chicken coops of pre-war suburbia, but magnificent modern buildings to match the splendours of 18th Century Bath and Georgian London. I want you to accept this commission and live and work with the Durham miners until this job is done."

Lubetkin moved to Shotton, apparently carried shoulder-high by miners enthused by the prospect of decent housing. He listened to how they wanted to live: high rise, they said, with lifts because, as deep miners, that's how they worked.

So Lubetkin planned a visionary townscape of concrete tower blocks of flats surrounded by acres of parkland.

But the National Coal Board thwarted him. It was not prepared to give up the 30 million tons of unmined coal beneath Lubetkin's high rise dreams. It said the surface should only have low rise properties so it could continue to hollow out underneath.

Lubetkin quit in 1950 without completing a single building, and Peterlee began to be laid out more conventionally with Sir George Grenfell-Bains, the man responsible for Newton Aycliffe, drawing up the residential area.

But his uncomplicated patterns were not grand enough for "the international capital of coal mining". Indeed, Lubetkin looked back with disdain and said Peterlee had turned into "a conventional new town, for miners' sons and daughters working in brassiere factories".

In 1955, to put the vision back into the Peterlee project, Victor Pasmore was taken on board as consultant director of urban design. He was an abstract artist who was the director of painting in the School of Fine Art at Durham university. His “constructivist art” was cubist and square, and although his homes are noted for the elegant way they fit into the landscape, they all had flat roofs which invariably leaked on the humans living inside.

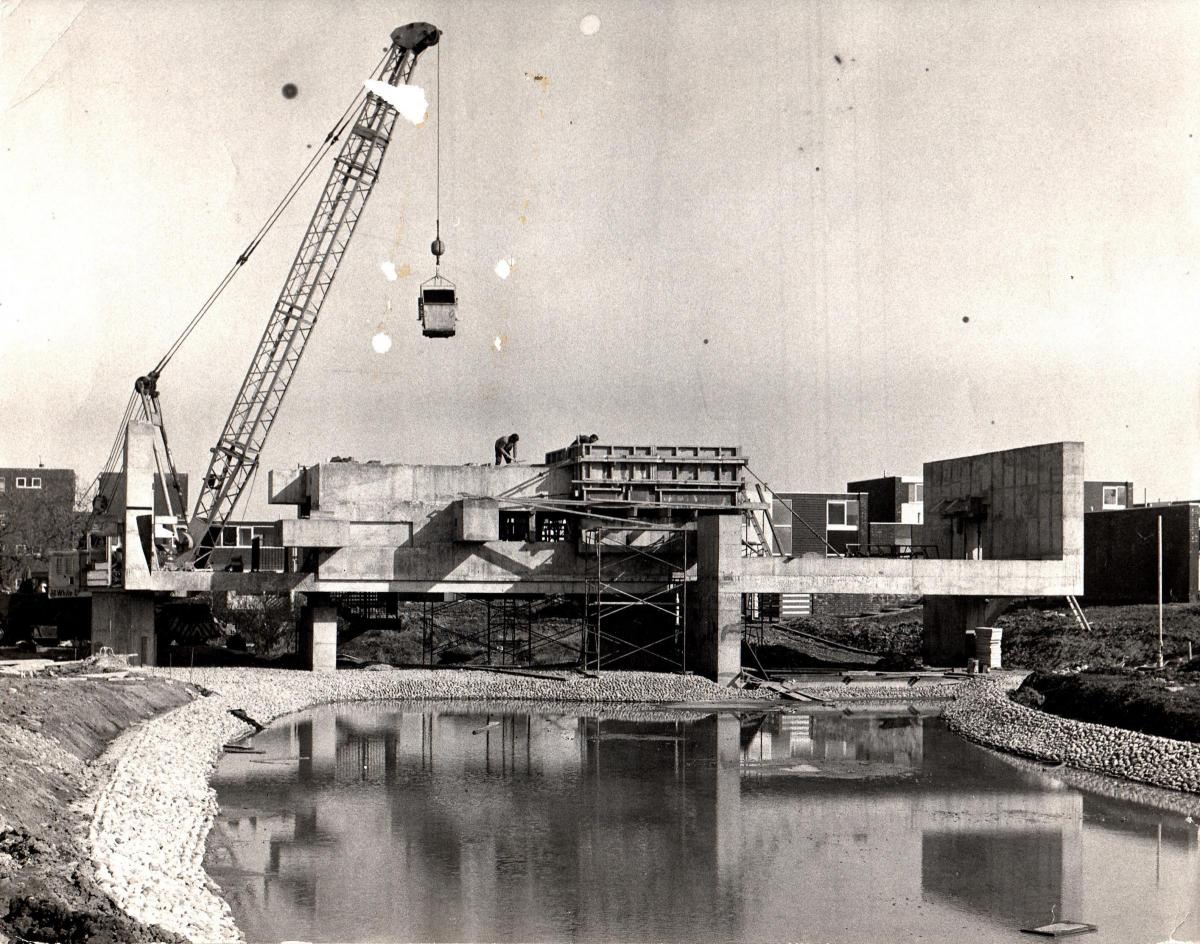

Pasmore’s piece de concrete resistance was to be a bridge across a beck in the middle of the Sunny Blunts estate. It was to be more than just a bridge. It was to be a conglomeration of concrete squares with the beck dammed beneath it to form a lake.

Pasmore described it as “an architecture and sculpture of purely abstract form through which to walk, on which to linger, and on which to play”.

Work began on the £33,000 creation in early 1969 and, of course, it was controversial – councillors wanted the money spent on something a little less pointless than a bridge over trickling waters.

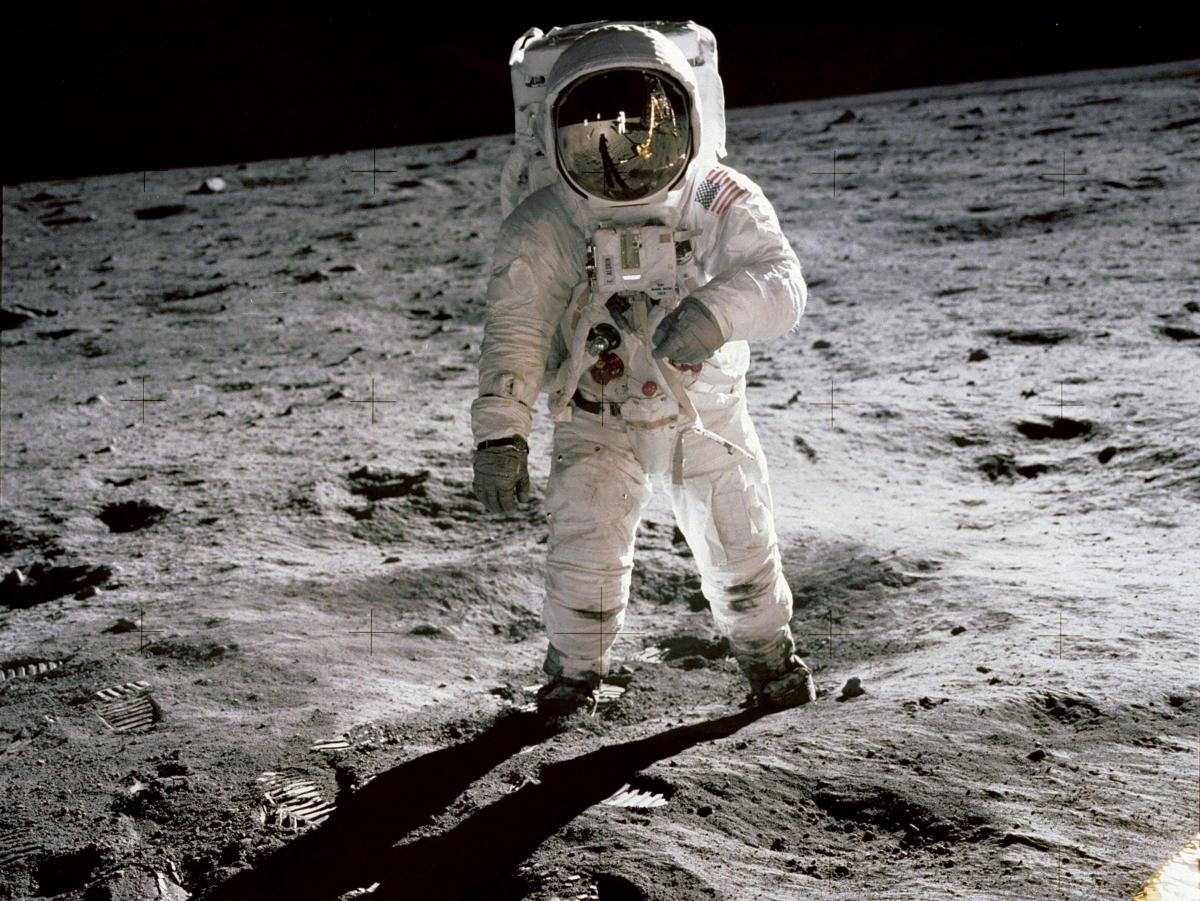

Pasmore wanted his construction to be named the Apollo Pavilion after the spacecraft that landed on the moon on July 20, 1969 – the space mission was the spirit of the age, all about hope, optimism and adventure, just like Peterlee itself.

But, perhaps because of the controversy, the Peterlee Development Corporation refused to officially give it any name, and allowed it to be opened without any ceremony on January 27, 1970, by which time it had been complete for several months.

The controversy didn’t go away, and, without anyone caring for it, its broad panels became covered in graffiti, its concrete corridors became a focal point for anti-social behaviour, and its stagnant lake filled with detritus. By the early 1980s there was a campaign to have it demolished, with local councillor Joan Maslin calling it "a dirty lump of concrete, no more than a monstrosity and an eyesore".

In 1998, English Heritage said the pavilion was "architecturally and historically important", but it took another ten years for the pavilion to find enough friends, led by another councillor, David Taylor Gooby, to support its application for a £400,000 restoration.

That was carried out in 2009, and the pavilion emerged with a Grade II* listing, putting it among the most important five per cent of buildings in the country.

Just as over time the Angel of the North has won over its critics, so the Apollo Pavilion has become less controversial – although it is certainly not loved in the way the Angel is.

But it survives, and it will be illuminated from 6pm to 9.30pm on Friday, March 22, and Saturday, March 23, to celebrate its anniversary. Artichoke, the organisation behind Durham’s Lumiere festival, have commissioned some Berlin artists to transform the brutalist squares into a light and video installation. Some of the projections will commemorate the moon landings while others will feature geometric patterns in the Bauhaus style which inspired Pasmore.

One of the great thrills of Lumiere in Durham has been the way the centuries old cathedral and castle have been transformed by light – now the pavilion is joining the pantheon of great backdrops.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here