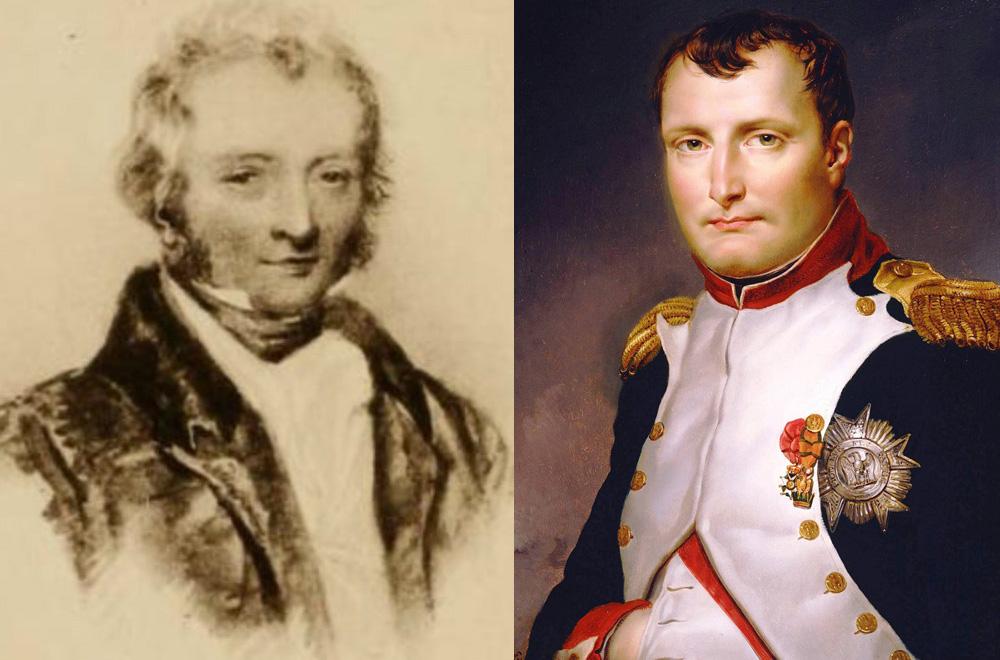

“I FELT dread in approaching the man whose fame as a warrior had reached the remotest corners of the earth,” wrote Dr John Stokoe in his diary on October 18, 1817.

Dr Stokoe had come a long way. He had been born in Ferryhill in 1775 and, after fighting the French at Trafalgar, had sailed 5,000 miles south to St Helena, possibly the remotest volcanic island in the world in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Dr Stokoe was the ship’s surgeon on HMS Conqueror, and now he was approaching Napoleon Bonaparte, the former French emperor whom the British feared so greatly that they had imprisoned him in the middle of the ocean.

As Dr Stokoe was led towards Napoleon by the Count de Montholon, he imagined he was meeting a monster, due to the way he was portrayed in the British press.

“The earliest idea I had of Napoleon was that of a huge ogre or giant, with one large flaming red eye in the middle of his forehead, and long teeth protruding from his mouth, with which he tore to pieces and devoured naughty little girls,” he wrote.

“I followed the Count who, on coming near, took off his hat, and presented me. I did the same and made my best bow, remaining, as the Count did, with my hart off, when Napoleon, after slightly touching his, addressed me in the following words: ‘Surgeon Conqueror, man-of-war. Fine ship’.”

Napoleon’s poor English meant that they switched to Italian to continue the conversation.

“During the short time I was in the presence of Napoleon, my opinion of his character underwent a complete change,” he wrote. “I had not been two minutes in conversation with him before I felt myself as much at my ease as if talking to an equal.

“I am not ashamed to confess that this sudden change was accompanied with such a friendly feeling towards him.”

Napoleon, though, was at war with his British captors, led by Sir Hudson Lowe. He adopted Dr Stokoe as his preferred medic, even though Sir Hudson had delegated a doctor to him, and Dr Stokoe advocated better treatment and less harsh conditions for the ailing patient.

The contact between ex-emperor and former Ferryhillian became so regular that on August 30, 1819, Dr Stokoe was court martialled on ten counts of illegally giving Napoleon favoured treatment and for spreading the “infamous and calumnious imputation” that Sir Hudson wanted to “put an end to the existence” of the captive.

The charges appear trumped up, Dr Stokoe was unrepresented and he could not call witnesses on his behalf. He was found guilty and dismissed from the Royal Navy, but as he had served since 1794 when he left Ferryhill as an 18-year-old to become a surgeon’s mate, he was allowed to keep his pension.

Napoleon died on St Helena on May 5, 1821, officially of stomach cancer, unofficially of arsenic poisoning. Whether the British were guilty or not, his demise was probably hurried along by the conditions in which he was kept.

Napoleon’s family, though, were so grateful to the man from Ferryhill that they enhanced his pension and paid him to escort their princesses on long sea journeys.

He returned to the North-East in the early 1840s, settling in Hallgarth Street, near the prison, in Durham. He married and had two children, both of whom died very young, followed by his wife.

On September 13, 1852, he had just visited his daughter’s grave in York when he collapsed in the station refreshment rooms and died, aged 77. His obituaries noted that he’d always wished to reverse the decision of the court martial, or at least present his side of the story to the British public, although he had never been allowed.

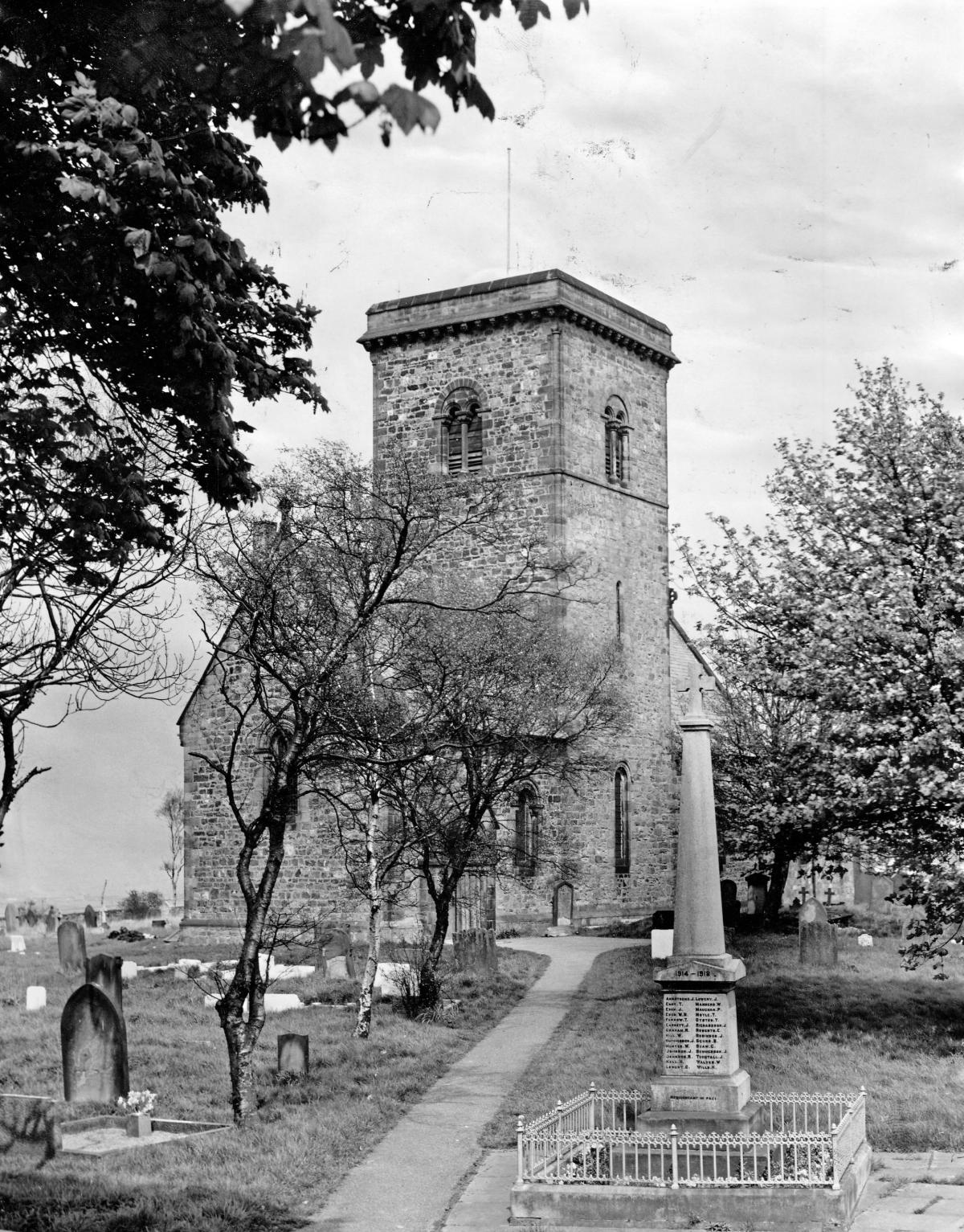

He was buried in Kirk Merrington churchyard, near Ferryhill. His headstone says: “The deceased, by his will, directs that the residue of his personal estate shall be invested and the dividends yearly divided among the necessitous and the deserving poor residing in Merrington and Ferryhill.”

Does Dr Stokoe’s legacy live on in any way today?

THE story of Dr Stokoe is one of many told in a lavish, even sumptuous, 362-page coffee table book entitled Ferryhill: A Visual History. It has been compiled by Ferryhill enthusiast Darrell Nixon, who has unearthed some amazing pictures which are displayed beautifully in the book, along with Ferryhill stories, such as the 1928 bank murder, the 1683 Brass murders and lots of other, less murderous tales.

The paperback book is available from Amazon for £35.99 or as a Kindle version for £17.99. No bookshelf in Ferryhill is complete without one.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel