ONE hundred and fifty years ago, the village of Thorpe Thewles was en fete. The top toffs in the area were getting married: Lord Ernest McDonnell Vane Tempest, of Wynyard and Seaham halls, was getting hitched to Miss Mary Townshend Hutchinson, who lived in just one hall, Howden Hall, which was on the outskirts of the village.

The villagers really pushed the boat out, creating triumphal arches, decorating the church with evergreens, covering the buildings with flags and filling the streets with “gaily dressed people”.

The Darlington & Stockton Times of January 16, 1869 reported: “On each side of the pathway to the carriages there were many hundreds of people, all anxious to get a glimpse of the smallest particle of the bride’s fluttering railments, and as her progress was slightly delayed by the crowds about the principal gate, the wishes of all appeared to be gratified. As she entered the vehicle, the sun for a moment shone feebly through the mist, and this omen of a happy future was hailed by a flattering cheer from the vast assembly.”

As the happy couple headed for their wedding breakfast at Howden Hall, where “cannon were fired incessantly from the lawn”, why would hundreds of people be clutching at the faint appearance of the sun for an omen that the future would be brighter than the past? What did they know that the local reporter only dared refer to with a nod and a wink to the knowing?

Ron Tempest, of the Wynyard Estate, has been in touch to paint a vibrant picture of his distant, but colourful, ancestor.

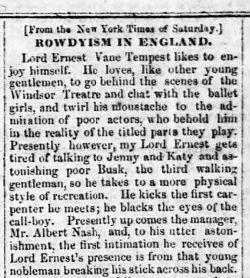

Born in 1836, Lord Ernest was a younger son of the late 3rd Marquis of Londonderry – the famous man on t’hoss statue in Durham Market Place. He’d fallen disreputably out of school at the age of 18 and ended up as a private in the army. Family connections earned him a commission as an officer, but when he was stationed at Windsor, he formed a romantic attachment with a young actress at the Gaiety Theatre.

He forced his way into her dressing room, and when the theatre manager objected, Lord Ernest punched him, threw him down the stairs and violently beat him.

The scandal went global, and Punch magazine published an unflattering ditty about him:

And what is my Lord Ernest Vane

He is a brat of nineteen

Whom our lady the Queen

In her service is pleased to retain

Ernest was fined £5, forced out of the Life Guards, and went opal mining in Australia.

When the scandal had died down, he returned and became a lieutenant in the 4th Dragoon Guards. He served in the Crimean War, but when back in Brighton he was involved in “the disgraceful ragging of two young cornets”.

Two younger soldiers were forced to take part in an initiation ceremony. One was found in a fountain in his nightshirt while the other, the son of a prominent clergyman, was pinned down on a sofa and Ernest cut off his whiskers.

One source says that Ernest explained his actions by saying he had taken exception to the soldier’s “peculiar English and pronunciation of the letter h”.

He was drummed out of the army for a second time, and when the shaven soldier pressed assault charges, he was forced to hide in his mother’s house in Park Lane, London, to avoid the summons. He was declared an “outlaw” and fled abroad, apparently without paying for some jewellery. The Times newspaper said he was “of Strephonic tendencies”, which is undoubtedly true although neither the Oxford English Dictionary nor the internet is able to provide a definition for the word “strephonic”.

Somehow, Ernest ended up in the American Civil War in the early 1860s, fighting under the name of “Captain Charles Stewart” – a family name – for the Union side in several of the epic battles on the River Potomac. On October 21, 1861, he was at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, in which the Union side lost more than half its 1,700 soldiers, but he was commended for his bravery.

Despite this uptick in his fortunes, he was estranged from his family in Wynyard. He hadn’t spoken to his mother for years and failed to attend her funeral in 1865.

But, by 1868, he must have mended some fences because he was back, and was selected as the Conservative candidate to be the first MP for Stockton.

He lost, polling 25 per cent of the votes in a two-horse race.

But he won the hand in marriage of Mary, the daughter of a Stockton iron merchant, and when the sun broke through the clouds as she left the church in Thorpe Thewles, the hundreds of spectators saw it as a sign that at the age of 33, the bridegroom was now entering a more settled period of his life.

They moved to Scarborough, and had a son, Charles, in 1871, but…

“They seem to have been estranged quite early with newspaper reports of a relationship between Mary and a mysterious Mr Hungerford, who was described as a close friend of the Prince of Wales who later Edward VII,” says Ron. “Ernest attempted to knock his head off!”

Then he adds as an aside: “There seems to be a bit of a theme here as his brother’s wife, Susan, allegedly had an affair with the Prince of Wales himself, giving birth to a daughter in secret who then disappears from the records – but that’s another story.”

Indeed it is.

Ron continues: “When Ernest died in Scarborough in 1885 aged 49, his obituary did not mention a wife at all.

“She apparently lived in the Scottish borders and survived him by five years – her death certificate says she died of pneumonia and mental instability, poor woman. Both are buried at Thorpe Thewles.”

Charles, their son, lived at Howden Hall on the edge of the village (it still stands, near the Tesco on the A177 north of Stockton). Lord Ernest’s grandson, Charles, was shot down over northern France in 1917 while serving in the Royal Flying Corps. He was captured but died within hours. There is a memorial to him in the church in Norton.

Very little survives of Lord Ernest, though – not even a photograph or a painting. The clouds have obscured his sun.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here