The Durham Book Fair is being held at Durham Johnston School next Saturday. But why does the school have such a particular name? One of the books on sale at the fair provides the answer

DURHAM JOHNSTON SCHOOL stands beside the old Great North Road on the site of the Battle of Neville’s Cross, fought in 1346. It is a startlingly modern collection of sharp shapes and random crashing colours but still, in big sans serif letters, it bears the name of its founder: Johnston.

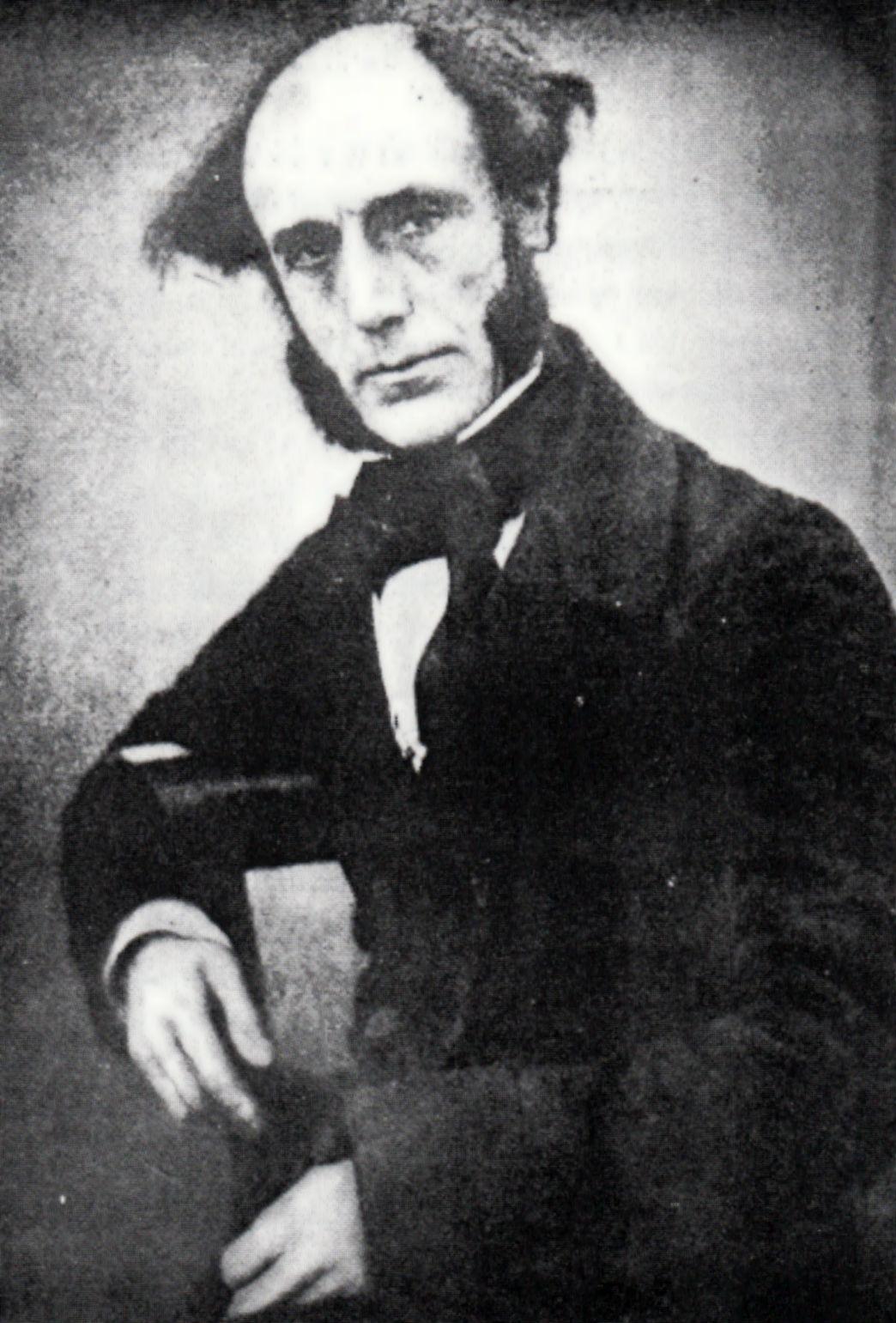

Professor James Finlay Weir Johnston, to give him his full title, and there is a degree of irony in the school which bears his name now being on the battlefield where up to 3,000 Scots were killed as he was born in Paisley in 1796.

He gained a Master’s degree from Glasgow university in 1826, winning awards for his work in Greek, Mathematics and Natural Philosophy. He then moved south and set up home in 56, Claypath in Durham – the house in which he was to die in 1855 and which now bears a blue plaque in his honour.

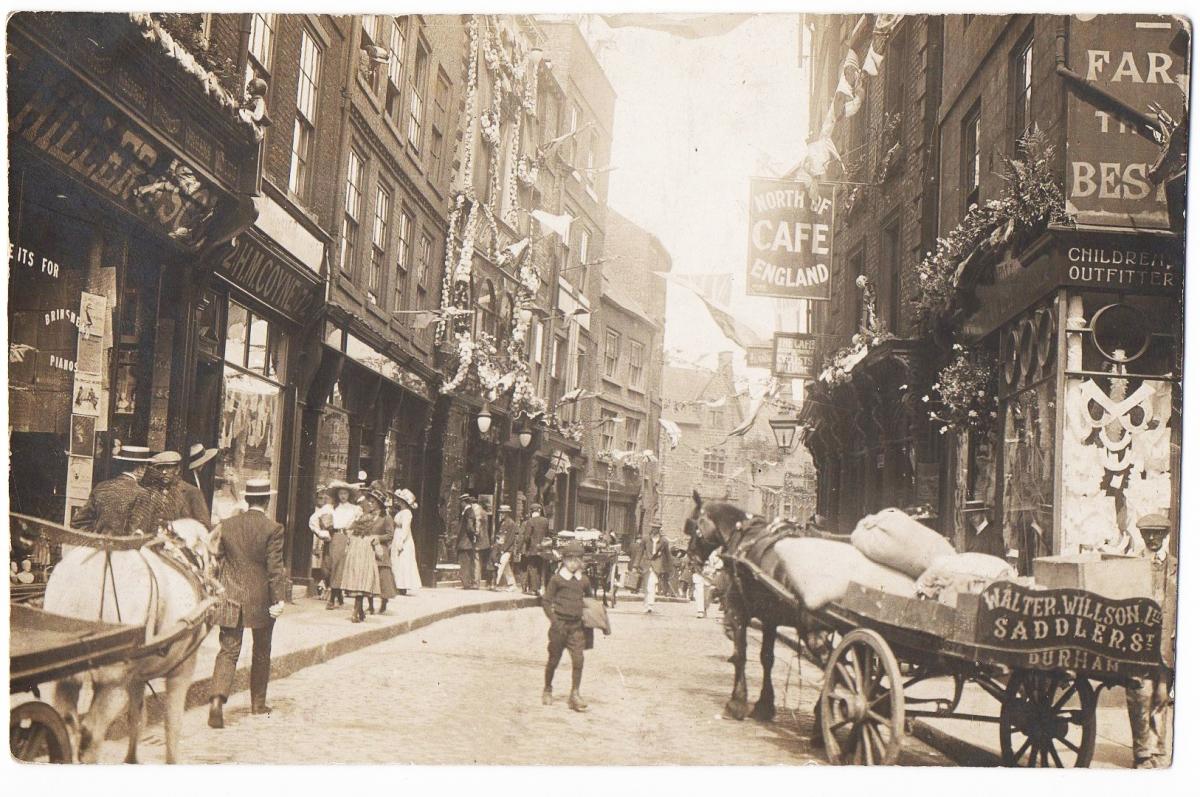

Why he came to Durham is unknown, but he must have spied a business opportunity, for he immediately set up a school in some upstairs rooms in Saddler Street. For £6-a-year, he’d teach your child English, reading, writing, arithmetic and geography; for £8, Latin would be added to the menu, and for £10, he’d throw in Greek, mathematics, plus a soupcon of French and “the rudiments of Italian”.

In his advert in the Durham Advertiser of January 20, 1826, he also offered to teach “chemistry, with experimental illustrations”. This inclusion of the sciences on his curriculum made his academy stand out from the many in the area.

But in 1829, Mr Johnston married Susan Ridley of Park End, near Hexham, who was 19 years older than him and was a lady of independent means. He was able to give up his academy and devote himself to his first love: chemistry. He went straight off to Sweden to study in the laboratory of Jacob Berzelius, who is regarded as one of the founding fathers of chemistry as he identified the silicon and invented chemical notation – O for oxygen, K for potassium.

Then he visited Hans Christian Ørsted, the chemist who discovered that electrical currents create magnetic fields, in Copenhagen.

Back in Durham, he was appointed a reader in chemistry and mineralogy at the newly-founded university, and he began a series of public lectures in Newcastle. These really made his name – “Johnston dismantled science of her severe garb and clothed her in the attractive form of popular instruction”, said one critic, and if he were around today, he would be a TV scientist, like Professor Brian Cox or Professor Robert Winston.

Johnston was also prepared to work beyond the bounds of academia: in 1834, the London Lead Company paid him 100 guineas for a series of lectures on geology to its workers in Middleton-in-Teesdale.

Perhaps it was this experience that gave him the idea to persuade Durham to offer the first university course in engineering and mining.

By 1851, fresh from a study tour of north America, he was at the height of his powers, working on his magnum opus, The Chemistry of Common Life, a two volume study of the composition of everyday things: one chapter tells of the make-up of Abyssinian coffee and Mexican cocoa, another looks at the differences between cider and perry.

That year, Britain was transfixed by science due to Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace – but it highlighted that Britain was beginning to fall behind other European countries because of its lack of technical training, or “practical art” as such skills were then known.

So in 1853, Johnston opened the Durham School of Art, which offered evening classes and Saturday schools in practical subjects like drawing, perspective and design. They proved very popular.

In 1855, Johnston returned after a tour of the continent with a lung infection. As he lay in his sickbed, he made two last requests. He had been a member of the sanitary board and was aware of the growing body of evidence about the dangers of graveyards in heavily populated areas – in the days when people had only a local well to rely on, water filtered through the decomposing remains in a nearby churchyard was understood to be unhealthy. He therefore requested that he be buried in a country church.

He also requested that, after the death of his wife, his estate such be put to “literary, scientific or educational” uses.

And so Prof Johnston died in 56, Claypath on September 18, 1855, aged 59, and was buried in Croxdale churchyard.

When Susan died seven years later, some of his money went towards establishing the Johnston Laboratory in Newcastle, where “practical art” was taught, but in the 1870s, the people of his adopted home city of Durham realised they were missing out and they vented their dismay in the letters page of the Durham Advertiser, the Echo’s sister paper.

In 1874, his trustees started evening and Saturday classes in practical sciences – maths, physics, geology – and by 1893, there were 300 students attending them in makeshift premises dotted around the city. It was decided that the remainder of his bequest – £4,200 (more than £500,000 in today’s values) in North Eastern Railway shares – should be used to establish a secondary school. At the time, the school leaving age was 12, and the city’s only secondary was Durham School which catered for the sons of the professional classes.

Two squalid houses in South Street, with views to the river, were bought, and demolished, and in 1899 Lord Durham laid the foundation stone of the Johnston Technical School. It was opened on May 23, 1901, when the great and the good processed from the mayor’s chamber in the town hall, along Silver Street, over Framwellgate Bridge and up Crossgate to South Street, where the chairman of the county council, Samuel Storey, was presented with a ceremonial key which he turned in the lock.

He said he hoped that the school would be a facility not just for city children aged eight to 16 but for “likely lads and capable girls” from the villages around.

The first 13 pupils arrived for lessons on September 1, 1901. They came from a wide range of backgrounds: two were the sons of schoolmasters, one was the son of the manager of the swimming baths, another was the son of a flour mill owner, one was the daughter of a signalman and Frances Guthrie, 16, was simply described as an “orphan”.

They took their places in the classes run by the first £450pa headmaster, chosen from 73 applicants, 33-year-old Simon Whalley from Canterbury, whose surname must have made even children of the more respectable Edwardian era snigger.

Since then, the Johnston School has grown enormously. First of all it extended into a stocking factory in South Street, and then, in 1954, it moved out to a 22-acre field at Crossgate Moor beside the Great North Road.

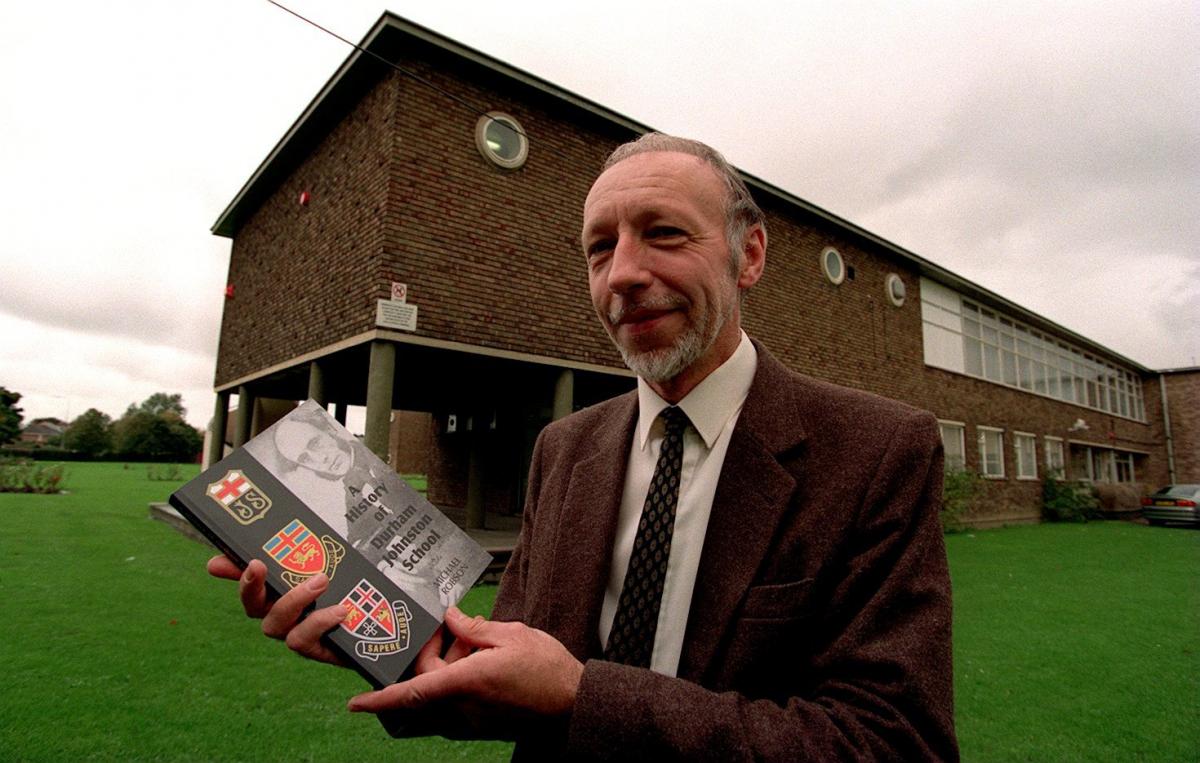

The story of the school and its founder was told in a book published in 1998 by art teacher Michael Robson, and a copy of that is among the treasures to be found among the second hand and antiquarian tomes at the Durham Book Fair which is held in the school on February 9, from 10am to 4pm.

Of course, the 20-year-old book doesn’t contain the most recent chapter in the school’s history – its complete rebuild between 2006 and 2009 into an educational cathedral of sharp shapes and random crashing colours which still, in big sans serif letters, bears the name of its Victorian founder: Johnston.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel