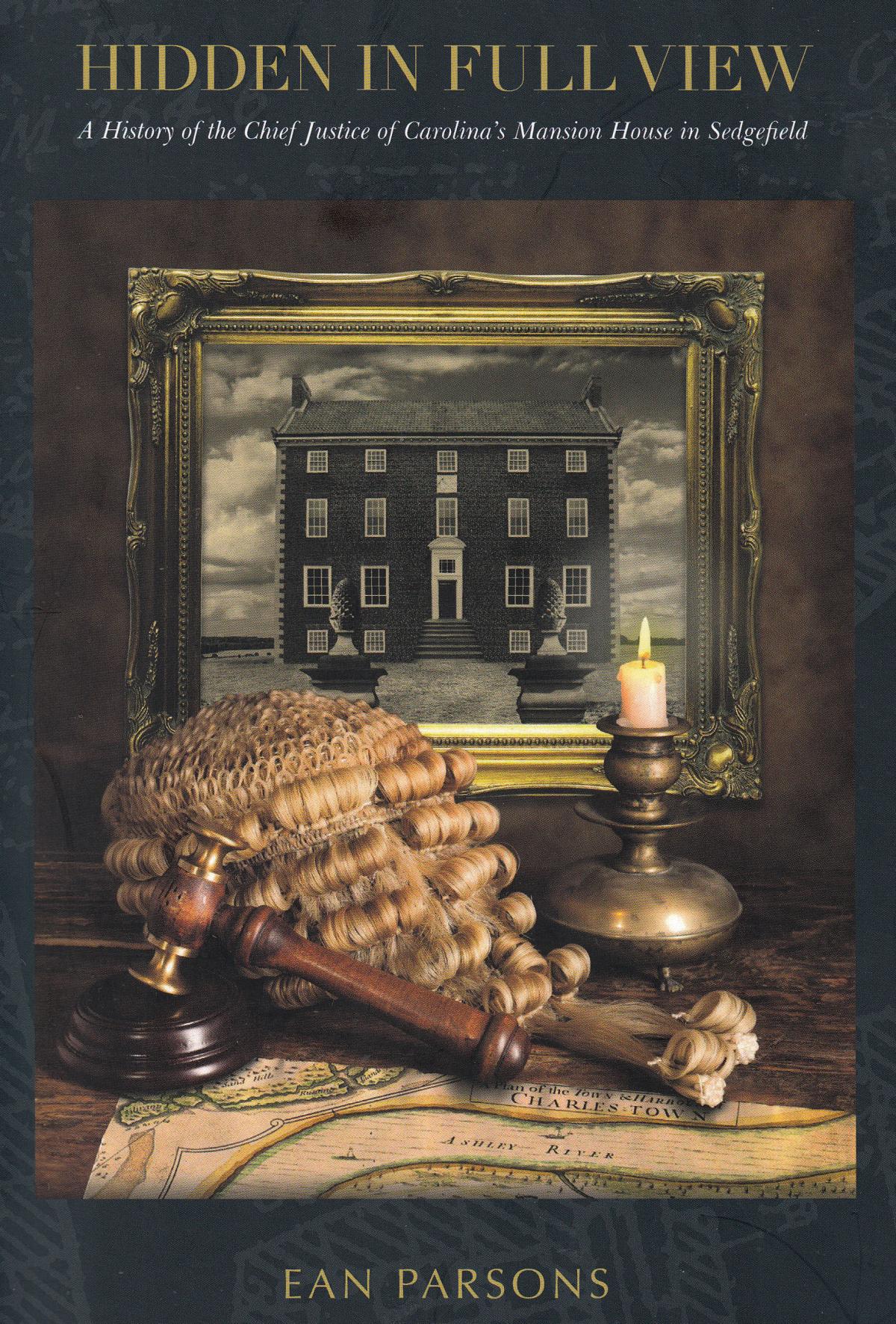

Hidden in Full View: A History of the Chief Justice of Carolina’s Mansion House in Sedgefield by Ean Parsons (£12.99)

THE Manor House in Sedgefield is a remarkably large and grand house overlooking the green which is itself rather overlooked because it is rather tucked away behind its wall.

Memories has enjoyed looking at it in the past because it has a couple of obvious curios: a mind-bogglingly complicated sundial above the main door and a pair of pineapples on the gateposts.

The sundial, dated 1707, is so complicated because the building faces east. The pineapples are special because they represent the height of luxury and extravagance – the pineapple (or “ananas” which means “excellent fruit”) comes from South America and would only grow in the hottest of British hothouses. Therefore, only the wealthiest people could offer their guests a taste of its stunningly sugar-sweet flesh.

But we always struggled to find out more about the Manor House.

In 2014, the author of the new book became the owner of the house, having rented offices on its upper floor since 2000, and intrigued by its blank canvas, set out to find out more.

The results of his researches now fill the 156-page and tell a great story.

He believes the house was built by Robert Wright, who was the North of England Judge of the Common Pleas in the late 17th Century. He was from East Anglia, and was the son of an eminent judge, Sir Robert, who became James II’s Chief Justice. However, Sir Robert fell dramatically from grace and died in 1689 in prison in London charged with high treason.

Young Robert, therefore, had little future in London and so came north to re-establish himself. Part of that re-establishment was finding a suitable wife, and although he was 23, he quickly married a 46-year-old Sedgefield widow, Alicea, from a well-to-do local family.

It was probably on prominent, raised plot of her land that he built his grand manor house, in rare and ostentatious red brick, with a sweeping view over the green straight at St Edmund’s Church. He completed it in 1707 by placing the sundial on its frontage – a statement of his arrival, and the pineapples on the gateposts hinted at the luxuries his important guests would find inside.

But this respectable northern judge was living a double life, for in Bloomsbury in London, he had a mistress, Isabella, and seven children.

In 1723, Alicea died aged 80 and was buried in Sedgefield. Finally freed, a week later, Robert married Isabella in London and then took her, with their seven kids, their servants and his favourite coach, to America, where he became Chief Justice of Carolina and a plantation owner.

He put his former life, wife, and manor house, in Sedgefield way behind him – although, intriguingly, there are parts of Carolina called Sedgefield. In South Carolina, there is a Sedgefield plantation near Goose Creek in which there is a Sedgefield school, and nearby at North Myrtle Beach there is a development of condominiums called Sedgefield.

Back in Sedgefield, County Durham, without Robert, the manor house lost the reason for its prominence, and was gradually relegated and occasionally became derelict. In 1799, it lost his command of the green when The Square was built in the middle of the grass, blocking its views to the church.

In the 20th Century, it became the offices of the rural district council and then a magistrates court, before again falling into disuse. Now it has been resurrected as a business centre and events venue which, after all these years, has been found to have an amazing back story.

Ean’s book is available by calling 07771 828 568 or email ean@manorhousesedgefield.co.uk

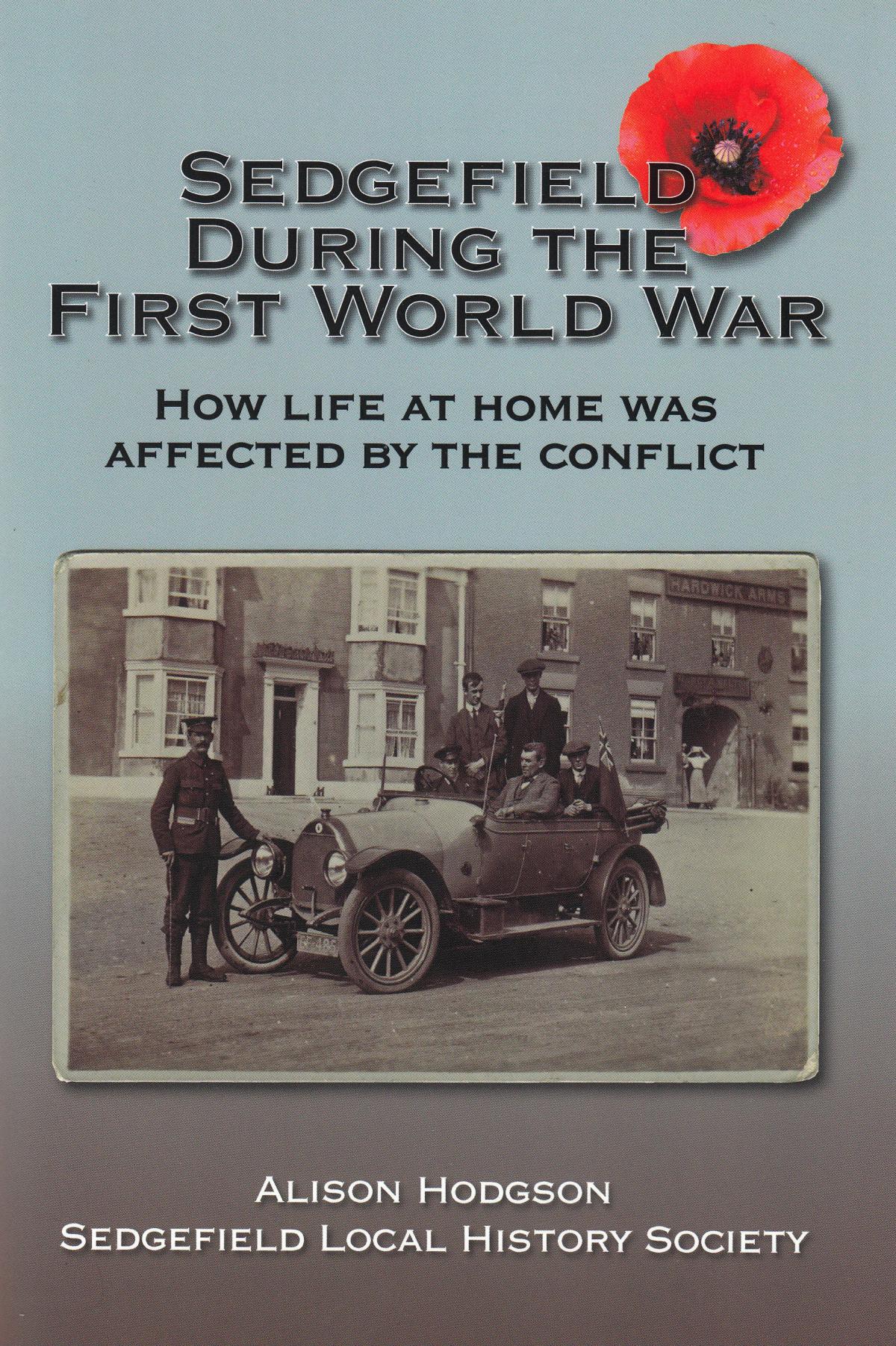

Sedgefield During the First World War by Alison Hodgson (Sedgefield Local History Society, £6)

ALISON, who is chair of the local history society, set out to find out about life at home during the conflict, and began trawling through wartime copies of The Northern Echo to find mentions of Sedgefield.

The result is a fascinating overview of day-to-day life, which tells of the entertainments people at home enjoyed, of how they were troubled by the black-out restrictions and a lack of horses, and of how they rallied behind their men with concerts, collections and knitting programmes.

In the early days of the war, the Echo encouraged local people to show their support by wearing khaki. It said: “Khaki reminds us of liberty, justice and honour: the redress of wrongs; the protection of the weak.”

Khaki became a fashion accessory. Alison says: “Men had the chance to purchase khaki shirts, socks, vests, Handkerchiefs and scarves. They could also sport khaki spats and boots. Even the ladies were able to wear a khaki hat trimmed with red, white and blue ribbons. There were coats, skirts, bags and belts in khaki, and there were also khaki items for children.”

Sedgefield would have heard the roar of the bombardment at Hartlepool and seen Zeppelins pass overhead.

Alison discovered how in July 1917, a motor charabanc took wounded soldiers recuperating at Brancepeth Castle on a daytrip to Blackhall Rocks. They broke their journey in Sedgefield.

“The quaint little town was looking its best when the party arrived to be received by Squire Ord of Sands Hall,” said the newspaper report, which also told how light refreshments were laid out on the village green. After these had been eaten, the men were presented with cigarettes.

As the local landowners, the Ords were important to the war effort, and the squire’s daughter, Miss Evelyn, encouraged women to knit and sew for the troops.

At the end of the war, she circulated an emotive letter asking for people to donate clothing for the victims of war.

She wrote: “Having seen the heartrending accounts of the terrible suffering from want and sickness endured by our Allies, who have been left behind by the cruel retreating enemy, like the battered relics of a rough ebbing sea, and feeling spurred on by the knowledge of their very great need – which they are bearing so courageously – I am making a Special Victory Appeal for them, in their misery and desolation.

“The released Ally Prisoners also will need feeding and warm clothing, and after having helped them thus far in their heroic struggle for existence, we are so anxious to assist in keeping them from another death from cold and famine. Do help, it will probably save a life.”

The well illustrated book is available from the town council offices, the post office and the Hardwick Park visitor centre.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here