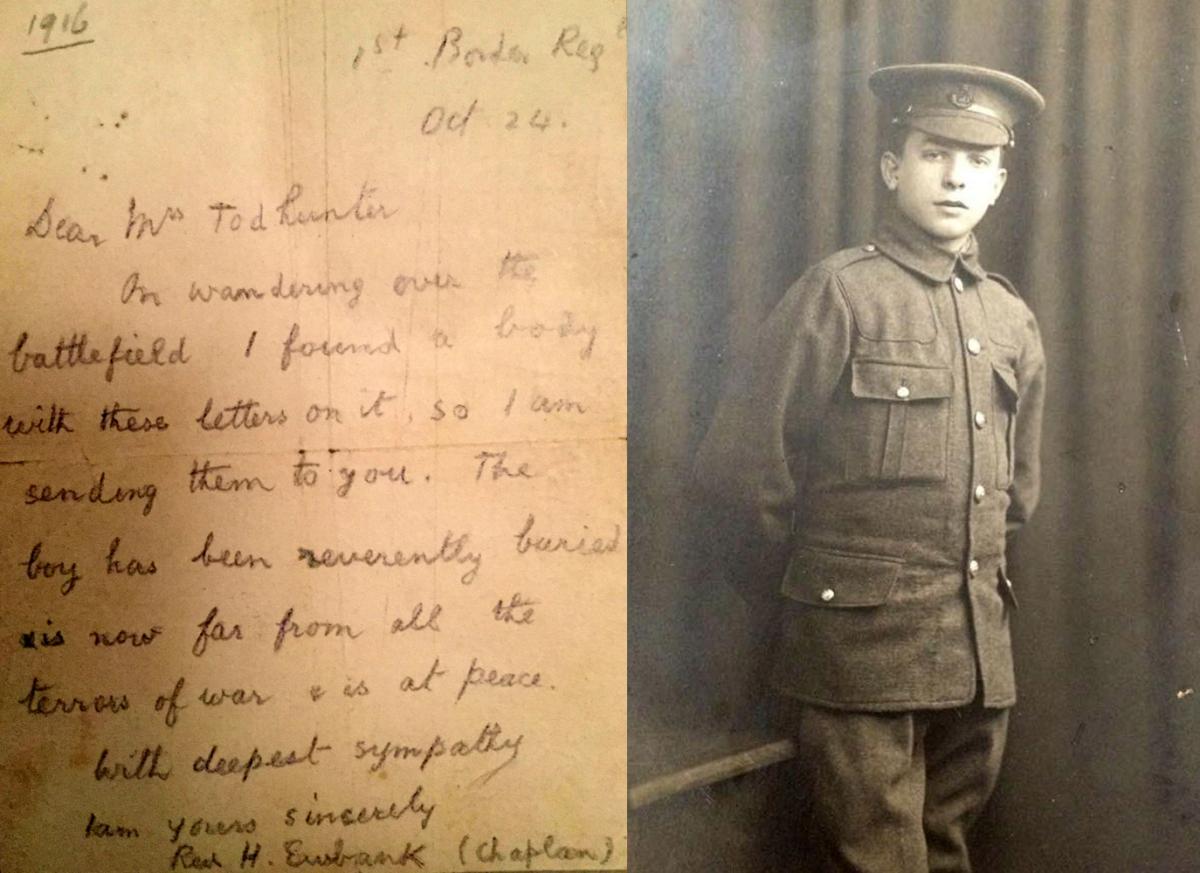

THIS pencil-written letter, on a tatty piece of paper, broke the news to Martha Todhunter that her 18-year-old son was dead.

It came from a chaplain who appears to have stumbled – quite literally – across the body of Private Alfred Todhunter at least a month after he had been killed on the Durham Light Infantry’s bloodiest day.

Martha was at home in 20, Grey Street, a terrace just to the west of Newgate Street in Bishop Auckland, when she received the letter. Her husband, Joseph, and three of her four boys were away fighting with the DLI.

FIRST NEWS: How Martha Todhunter learned that her son, Alfred, had been killed

The Reverend H Ewbank, of the 1st Border Regiment, told her: “On wandering over the battlefield, I found a body with these letters on it, so I am sending them to you.

“The boy has been reverently buried and is now far from all the terrors of war and is at peace.”

Presumably the letters which the chaplain sent to Martha identified which of her men had been killed, although the enclosures have not survived.

Video: Chris Lloyd tells the story of the "Fighting Bradfords"

Martha’s husband, Joseph, was a tailor, but her boys – Walter, Thomas, Alfred and Norman – all left school and went to work down Newton Cap Colliery. When war broke out, Walter was old enough to join the DLI legitimately, but both Alfred and Norman lied about their ages and enlisted when they were 16 (Thomas was unable to serve because he had been disabled in a motorcycle accident).

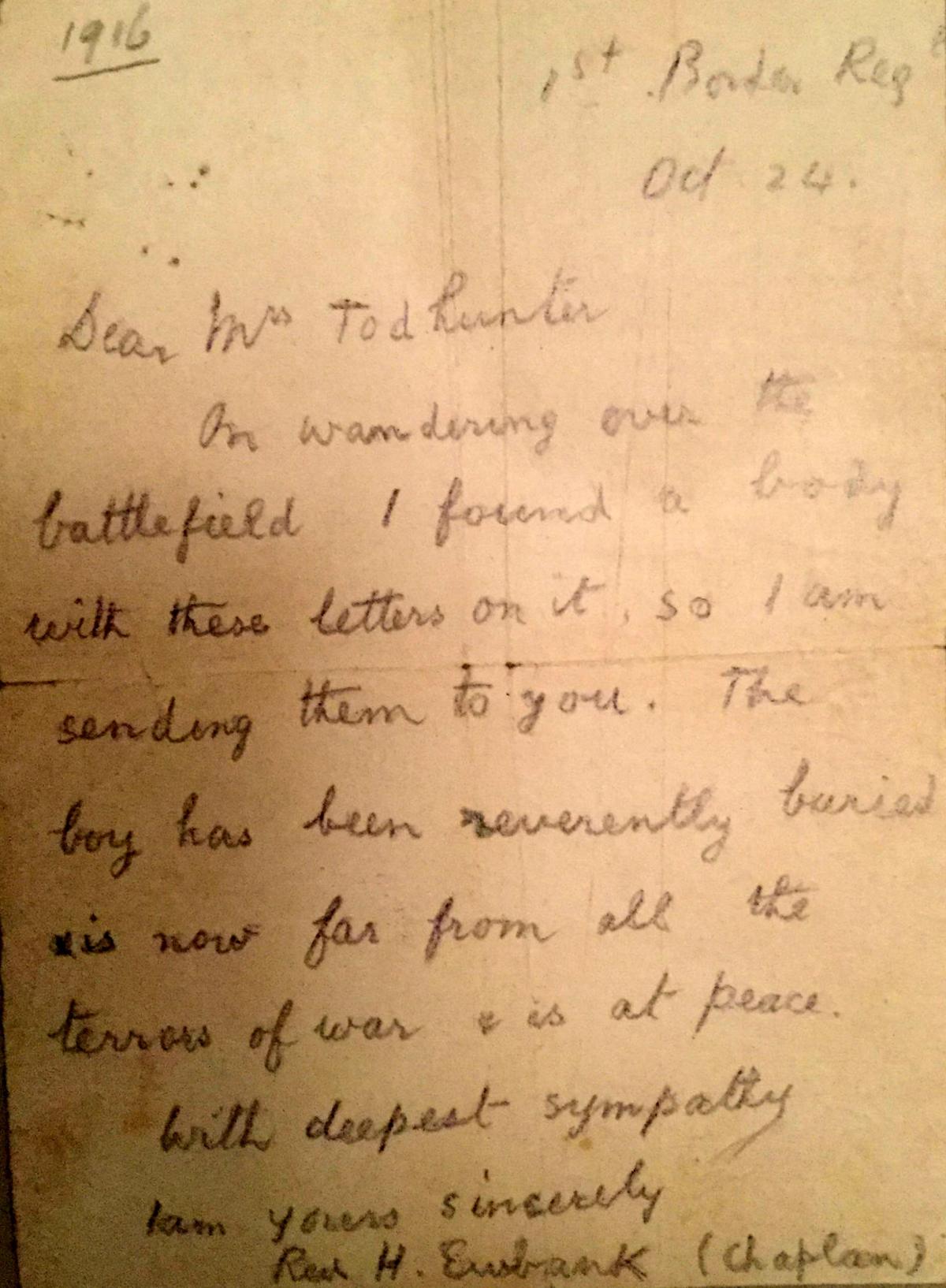

Alfred, who looks amazingly fresh faced in his khaki photograph, went into the 15th DLI. He would have landed in northern France on September 12, 1915, and fought through at least two major battles on the Somme before his number was up.

That was on September 16, 1916, at the Battle of Flers Courcelette – the battle in which the British employed their terrifying new weapon, the tank, for the first time.

Ten battalions of the DLI were involved in the battle – it is said that Joseph met Alfred near the battlefield just a few hours before the battle began – but 15DLI bore the brunt.

They advanced at dawn: the British heavy guns lay down a bombardment in front of them, the Germans launched a high explosive attack just behind them. The air in the middle was full of terrifying noise, flying shrapnel, lethal machine guns and, of course, Durhams.

It was carnage. The most advanced of the Durhams reached within 70 yards of the German lines, but got bogged down in shellholes. They were unable to move, quite literally because of the mud and also because any movement would attract enemy fire. They couldn’t even light their red flares to tell their own side where they were because they were too damp and because the British guns would also have turned on them.

Under the cover of dusk, the 200 living Durhams retreated, leaving their fallen comrades in blasted no man’s land.

The 15th DLI suffered 419 casualties that day – men killed, injured, missing, captured.

Over the two days of the Battle of Flers Courcelette, the ten Durham battalions had 514 men killed.

One of those 514 was Pte Alfred Todhunter. As the chaplain dated his scribbled note “Oct 24”, and one presumes he wrote it as soon as possible after making his grim discovery, it would appear that his body had lain there for more than five weeks.

Perhaps it was some consolation for Martha to learn that, at last, Alfred had been “reverently buried”.

But, to compound the tragedy, as the battle wore on, and the same ground was fought over time after time after time, the site of the reverent burial became lost, and so now Alfred has no known resting place. His name is one among the 72,337 names on the Thiepval monument which is dedicated to those who have no known grave.

With many thanks to Pte Alfred Todhunter’s niece, Patricia Mendham, who lives in Kings Lynn. The other three fighting Todhunters made it home to Bishop Auckland safely.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel