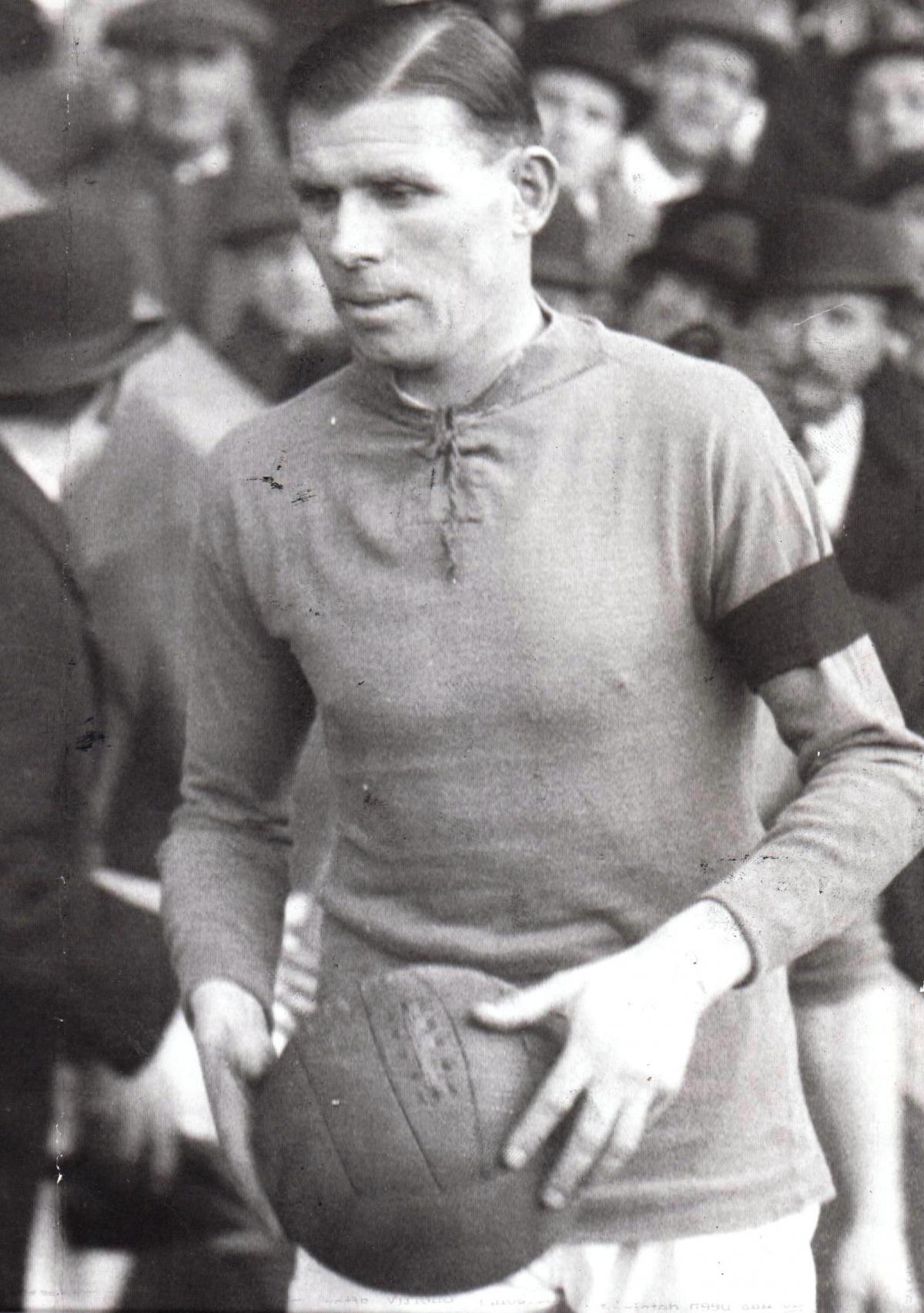

CHARLIE BUCHAN is still Sunderland’s greatest league goalscorer – even Kevin Phillips’ 113 goals come nowhere near Buchan’s 209.

Yet it would have been very different if a German bayonet, thrust in anger on the Somme, had not passed harmlessly between his toes.

His is a remarkable record and a remarkable story. He was a 20-year-old Londoner who arrived for £1,200 at Roker Park in 1911, and the following season he was their leading scorer as they won the First Division title and reached the final of the FA Cup, where they lost 1-0 to Aston Villa.

In fact, Buchan, who could score any kind of goal but specialised in glancing headers, was Sunderland’s top scorer every season from 1912-13 to 1923-24, although of course there was a break from 1915 to 1919, when his international career was also interrupted and so he was limited to just six England caps.

When the war broke out, he was determined to join up, but the Football League kept on playing until the end of the 1914-15 season, so Charlie was contractually obliged to remain on the pitches rather than in the trenches.

“Every weekday we went through military training, with broomsticks instead of rifles, from an army instructor – preparing for the day when we could do our bit,” he recalled in his 1955 biography, A Lifetime in Football. “That day came at last and I went to the recruiting office in Sunderland. ‘You’re big enough for the Grenadier Guards,’ said the sergeant. ‘That suits me,’ I replied.”

He was sent to London for training, and was allowed to turn out in exhibition matches for Chelsea.

“Training was tough, but I know it did me all the good in the world,” he wrote. “I was proud to belong to the Grenadier Guards.”

He was promoted to Lance-Corporal, and his 3rd Battalion was sent to the Somme, near Mericourt in northern France, in mid-July 1916, just two weeks after the great battle had started.

Charlie, naturally, was put in charge of the battalion’s football team, and organised a match that July. “No sooner had we started than German shells began to drop perilously near,” he wrote. “We restarted on another pitch. The game had to go on!”

He first went into battle on September 15 at Ginchy, when the 3rd were issued with sandwiches and rum at 5.45am so that they were ready to go over the top, supported by tanks, at 6am. In appalling conditions, it was carnage: 380 men and 18 of the 21 officers in Charlie’s battalion were either killed or wounded.

He remained on the Western Front throughout 1917, fighting at Passchendaele in Flanders and in northern France, where he won a Military Medal which was gazetted (ie: formally awarded) on December 12. A MM didn’t come with a citation, and his biography is remarkably short on wartime details, but the incident appears to have happened at Bourlon Wood near Cambrai.

His unit was pinned down, so Charlie took the lead in trying to break-out to safety. With his men close behind, he stormed a German look-out post, killing all but one of the enemy. That soldier, though, was armed with a bayonet which he rammed into Charlie’s boot.

This was a potentially devastating blow for a professional footballer, but the blade passed miraculously between two of Charlie’s toes, and he later said he survived the war “without a scratch”.

His nomination for the MM was enhanced because, that same day, under enemy fire, he used his footballing skills to sprint back to the mess tent to get his men hot food as their supplies had run out.

Soon after receiving the award, he was put forward for a commission, and in early 1918, he began his officer training at Catterick. He was promoted to Temporary 2nd Lieutenant, the rank he held when he was demobbed.

He returned to Sunderland, and resumed scoring goals. He played eight matches in the 1919 Victory League, and scored six; in 1922-23, back in the First Division, he was the leading scorer in the country. His legend grew when, ahead of the 1922 Tyne-Wear derby, he was offered a bribe of £1,000 to ensure Sunderland lost. He refused, reported the matter to the police, and scored in a 2-1 win at St James’ Park.

In 1920, Buchan played Minor Counties cricket for Durham.

His time at Sunderland came to an end in August 1925 when, aged 34, he was signed by Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman. Sunderland wanted £4,000 for him, but Chapman beat them down to £2,000 plus £100 for each goal he scored in his first season. As he scored 21, Arsenal ended up paying £100 more than Sunderland had asked for!

He was a remarkable goalscorer. In 379 league appearances for Sunderland, he netted 209 times. In 102 for Arsenal, he scored 49 times. For England, he was capped six times and scored four goals.

In retirement, he became a well known football journalist for the News Chronicle, even covering England’s first foray into the World Cup in Brazil in 1950. The following year, he published his own, successful magazine, Charlie Buchan’s Soccer Monthly.

He died on June 25, 1960, in a hotel in Monte Carlo of a heart attack, shortly after enjoying a large win in the casino.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here