Victoria Oxberry tells the First World War love story of Connie and Angus which has been unfolding on the Durham at War blog

WHEN the armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, Connie and Angus Leybourne were just starting out in married life in the North-East.

But like so many young couples of their generation, their path to the altar was far from uneventful. Long periods of separation, the loss of friends and relatives, and Angus’ capture and imprisonment in a German prisoner of war camp all had to be endured before the pair could live happily ever after.

It is a love story that unfolds within the letters they exchanged, letters that volunteers Margaret Eason and Judith James have transcribed for the Durham at War project.

Margaret, from Darlington, has been writing a blog about Connie and Angus, entitled A Very British Romance, for the Durham at War website, which maps out the experiences of people in the North-East during the First World War.

The letters, which are on loan to Durham County Record Office from Angus’ family, are beautifully written, thoughtful and restrained, and reveal a relationship based on quiet affection and mutual respect.

This is especially evident when Angus asks for Connie’s hand in marriage. As a prisoner of war, he is unable to propose face-to-face, and his hope and anxiety shines through the lines of his polite ramblings.

Having “gauged your feeling on the matter”, he writes: “Faint heart never won fair lady so I am making the plunge and I can only trust that you do not think me too presumptuous as regards your affection.”

He signs off: “Heaps of love from your affectionate friend, E. Angus Leybourne.”

On another occasion, he writes: “I am yours to a cinder.”

In her response, Connie writes: “If we are engaged I shall feel I can write any “Tommy rot” I like to you and you to me and we will grow to understand and love one another more and more, so let us be…Yours as before, Con.”

This gentle and often poetic language is typical of their letters. Theirs was a long-distance courtship in uncertain times, when strict conventions still shaped relationships between men and women.

However, to understand the importance of the letters as a record of the First World War, it is necessary to go back to the beginning.

Constance Dora Kirkup was born in Cornsay, County Durham, in 1889. Before the war her younger brother, Philip, joined the local territorial force, the 8th Battalion Durham Light Infantry (DLI) as a junior officer, and Connie came to know his close friend, Captain Elliot Angus Leybourne, another young DLI officer.

Angus had only been on active service for a few days, in April 1915, when he was seriously wounded and captured during the Second Battle of Ypres. Connie and Angus corresponded throughout his imprisonment and their letters provide a first-hand record of Angus’s experience in captivity, as well as Connie’s on the home front.

For example, on February 7, 1916, when Connie was volunteering as a nurse at Birtley munitions factory, she wrote: “We are kept very busy at the hospital that I told you I was going to work at. I am now installed there as Matron, Matron mark you!!! There is a serious side to the work, we had a fatal accident the other day. A Belgian, internally injured by a crush, he died about ten minutes after he was brought to our hut.”

After Angus was captured, he was held at a German PoW camp until May 1916, when he was one of the first British prisoners to be sent to neutral Switzerland on the grounds of ill health under a scheme organised by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

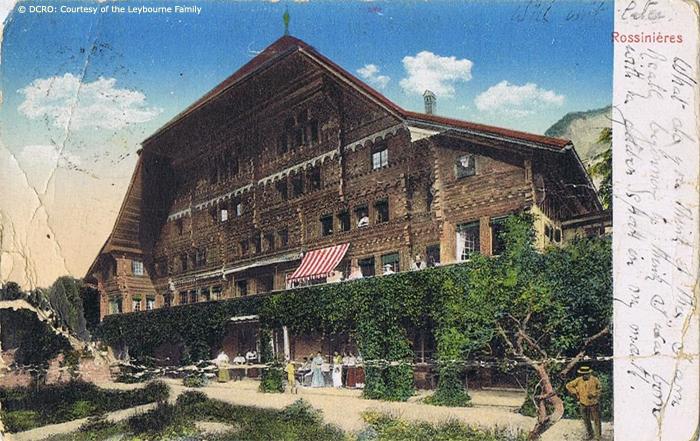

By June 2, 1916, he was residing in the Hotel Grand Chalet in Rossiniere. Wives and families were allowed to visit the prisoners, and it was the thought of being united with Connie that prompted Angus to propose.

Researcher Margaret says: “I’d never heard of the Red Cross scheme and it was fascinating to read Connie and Angus’ descriptions of what life was like in Switzerland.

“As Angus’ fiancée, Connie was allowed to visit and she stayed for a few months, immersing herself in the community that established itself there.

“It was a privilege to transcribe these letters and I hope I have done Angus and Connie justice. I feel I’ve got to know these two remarkable young people over the last few years, and I’ve developed a strong affection for them.

“When I first started I didn’t know how the story would end. I didn’t know if Angus would survive or if they would go on to get married. I was hooked and simply had to find out what happened to them. I’m so grateful to Angus’ family for sharing their letters with us.”

Angus was repatriated in December 1917. He and Connie married on October 16, 1918, at St George’s Church in Jesmond and went on to have two children. Devoted until the end, they were living in Springwell in Gateshead when Connie died on January 25, 1950.

Angus died less than two months later.

To see Margaret’s blog and for further information about Connie and Angus, go to durhamatwar.org.uk/story/12522

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here