Chris Lloyd tells the story of a nurse from south Durham who spend four years patching up soldiers on the frontline until she, too, became a victim

ON March 21, 1918, the Luftstreitkrafte – the First World War forerunner of the Luftwaffe – got lucky.

They bombed a railway station in the northern French town of Lillers, which is about 30 miles south of Ypres, and struck a train loaded with ammunition. It exploded, showering the town with fiery, deadly lumps of shrapnel.

This was desperately unlucky for “the angel of Spennymoor”, Sister Kate Maxey, because next to the railway station was a British casualty clearing station – it accepted injured soldiers direct from the frontline, patched up those who could be patched up, and those who couldn’t were sent to general hospitals for treatment.

Or to the mortuary.

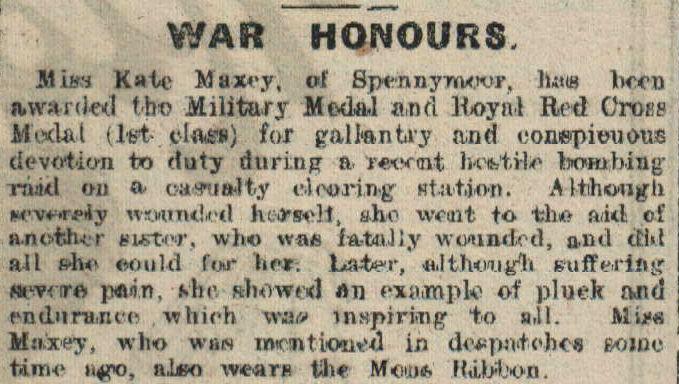

Maxey – she was known by her surname throughout the war – was the sister-in-charge of the clearing station when the Luftstreitkrafte struck lucky. She was hit by shrapnel in the head, neck, arm, thigh and leg. She received a spinal injury that restricted her movement, and her eardrum was perforated.

But still she carried on nursing.

Immediately after the explosion, she went to the aid of a fellow sister who was mortally wounded.

Even as her own pain grew worse, Maxey, 41, carried on. Her commanding officer wrote in his official report: “When lying wounded, she still directed nurses, orderlies and stretcher bearers and refused aid until others were seen to first.”

When she was finally treated, it was discovered that she was too badly wounded to be patched up. Instead, she was shipped back to Spennymoor, to recuperate at her sister’s house, and so her four years of active service came to an end.

Spennymoor was her home town, as she had been born in 1876 in 30, Clyde Terrace, which still stands. Her father was a shopkeeper on the High Street – he ran an emporium, calling himself a “wholesale jeweller, cutler and general hardware merchant, importer of French and German toys, china, Bohemian Glass etc, and wholesale draper”. Her relatives, the Deftys, have the store today.

When she was 15, Kate and her sister Amelia moved to Leeds, where her aunt lived with her physician husband. Amelia used the opportunities of the big city to train as a milliner; Kate followed in the footsteps of her uncle, and in 1903, qualified as a nurse at Leeds General Infirmary.

She was called up at the outbreak of war in September 1914, and by October 9, she was in the thick of the action, being stationed at No 8 General Hospital in Rouen, before being moved to a casualty clearing station near Ypres.

She spent most of 1915 there before being moved to No 1 General Hospital at Etretat, near Le Havre, on the French coast. Here she received the wreckage of the men – like the Durham Pals – caught up in the Battle of the Somme.

She was promoted to sister, and in November 1916, Sir Douglas Haig praised her in despatches “for gallant and distinguished service in the field”.

Maxey stayed on the Somme throughout 1917 and into 1918 until the bombing of the ammunition train in Lillers forced her return to Spennymoor.

In the King’s Birthday Honours of June 4, 1918, her heroism under fire was recognised as she was awarded the Military Medal and the Royal Red Cross Medal, the monarch’s citation saying that she “showed an example of pluck and endurance which was inspiring to all”.

To add to her honours, while she was recuperating, the Spennymoor Ambulance Brigade and Nursing Division presented her with “a silver set of salts and spoons”.

By August, she was fit enough to return to service, and although she wanted to get back to the Somme, she was ordered to Leeds infirmary.

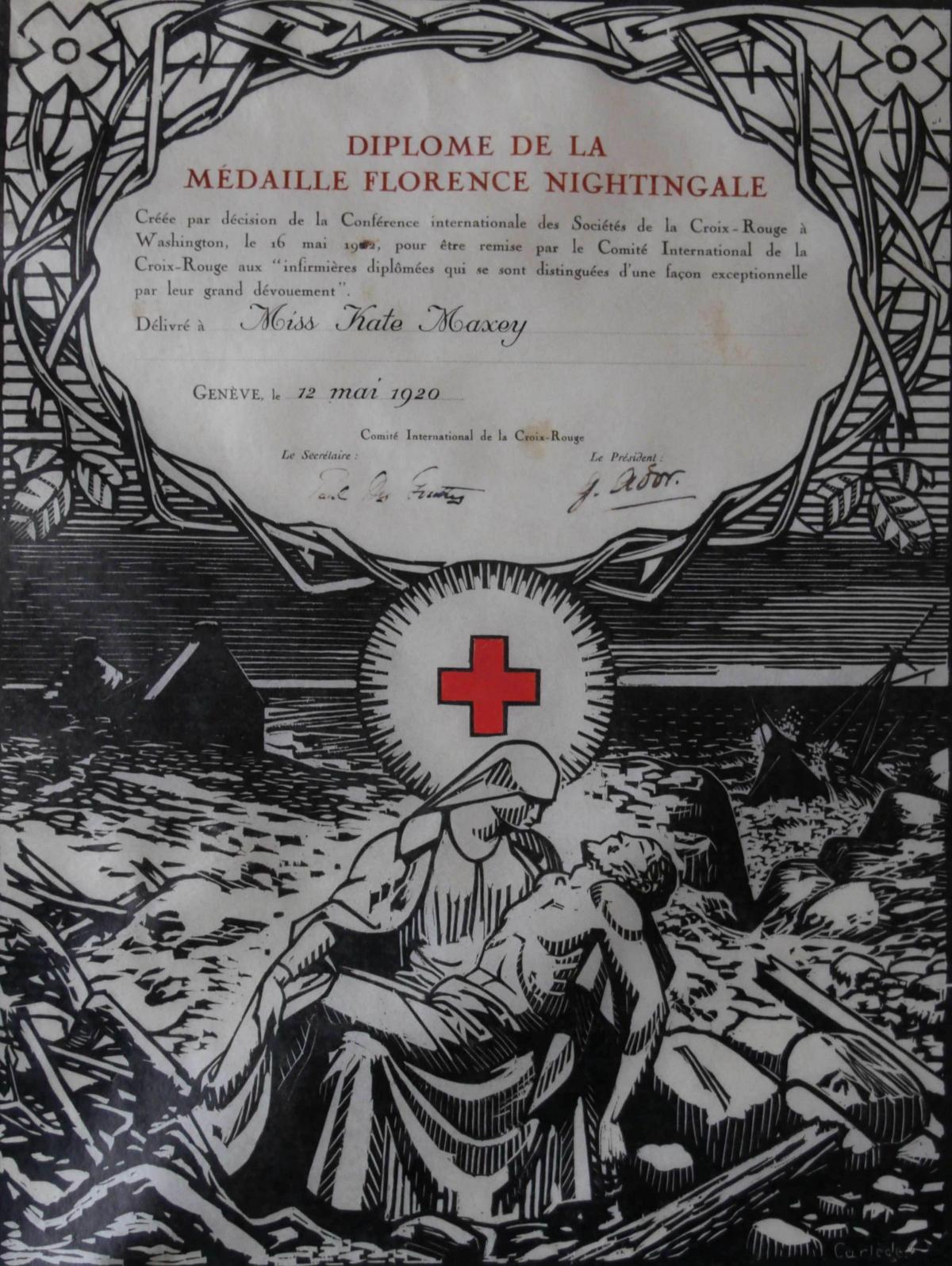

Maxey was demobbed in June 1919 and with a colleague set up a nursing home in Halifax. A year later, she became one of the recipients of the Florence Nightingale Medal, awarded by the International Red Cross.

In 1931, she retired from the nursing home, and spent her days living in London and on the south coast, although she died in 1969 in Bishop Auckland.

Getting behind the story of Behind the Lines

FIRST-HAND accounts and memorabilia played a starring role in a community’s quest to celebrate the courageous nurses and medics who risked their lives to save others on the Western Front.

Last month, Behind the Lines, a compelling film produced by Lonely Tower Film and Media, was released to great acclaim at community venues across the North-East.

Commissioned by Tudhoe and Spennymoor Local History Society, the film drew on more than four years of research by residents united by a passion to tell the stories of those who served in the nursing service and Royal Army Medical Corps.

It was inspired by Sister Kate Maxey, whose story was one of many uncovered by John Grainger, Harry Fairish, Dr John Banham and the late Bob Abley while preparing for the Spennymoor Great War exhibition.

The exhibition in 2014 encouraged the local community, including Maxey’s family, to come forward with further information, and the project grew to look at other Spennymoor residents who served in the Royal Army Medical Corps. The story was posted on the Durham at War website, and record office research revealed further nuggets.

The hard work attracted the attention of Mark Thorburn and Marie Gardiner, of Lonely Tower Film and Media, and with the help of a £10,000 Heritage Lottery Fund grant, they were commissioned to make a film.

Dr John Banham, who co-ordinated the project for the history society, said: “As historians we rely on primary sources to gain a fuller understanding of a particular time period. History books are fantastic but it’s only when you go back to the original material that you really feel a connection to the people you are researching.

“That is why places like Durham County Record Office are so important; they are preserving the voices of the past, voices we can learn a lot from.”

Mr Thorburn added: “We have been fortunate enough to work on so many wonderful and creative First World War projects with groups and individuals in County Durham.

“The resources and information held at the record office have provided fascinating detail and the team there are incredibly supportive.

“The hard work and dedication that has gone into the Durham at War website is a lasting tribute not only to the county’s Great War story, but to the many researchers, historians and individuals who have worked tirelessly to explore and share their findings.”

To find out more about the project, visit www.durhamweb.org.uk/tslhs/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here