SPENNYMOOR is a town built on iron and steel, and so slagheaps once dominated its horizons – not the pitheaps that are the legacy of coalmining.

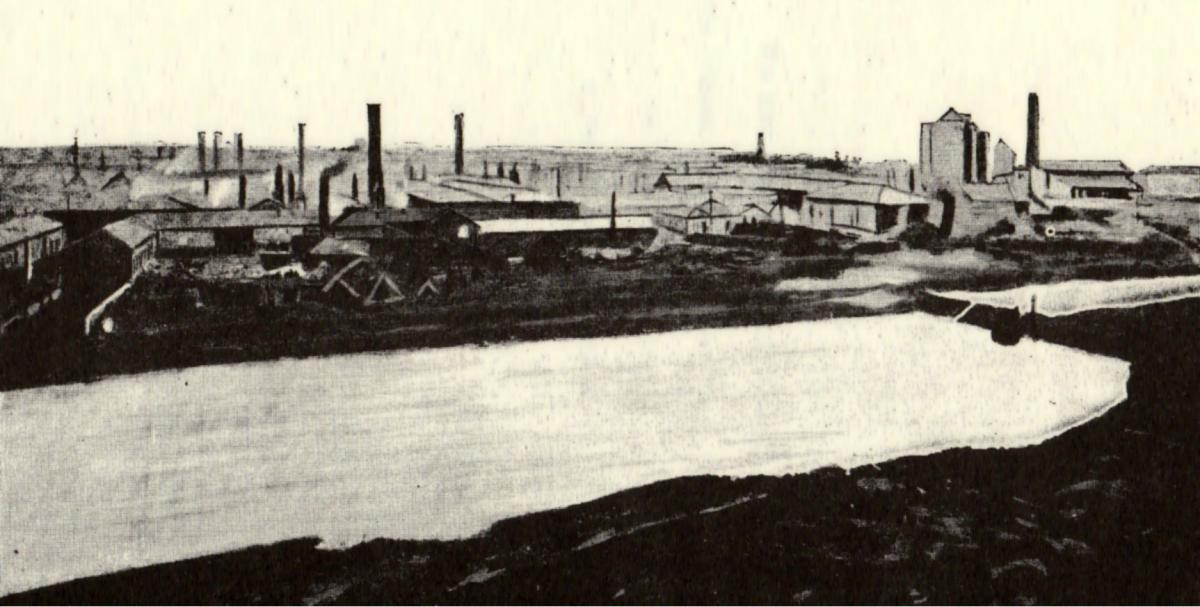

True, coalmining was its first industry in the 1840s, inspired by the first railways creeping onto its moor, but boomtime began in 1853 when Barings Bank established an ironworks at Tudhoe.

Barings had already financed Charles Attwood, a glass and soap manufacturer from Gateshead, as he had established an ironworks in Tow Law in 1844, using the ironstone of Weardale as his raw material. In 1853, Attwood wanted to refine his processes, and so called on his bankers once more to help him establish the Tudhoe ironworks to work the Weardale pig iron.

Suddenly Spennymoor had industry, especially as Attwood was a brave entrepreneur. In 1861, he applied the revolutionary techniques of his friend Henry Bessemer which converted iron into stronger steel.

The first four ingots of Spennymoor steel were rolled into rails that were laid across the High Level Bridge in Newcastle, announcing the arrival of both Spennymoor and steel.

Coalmines grew up around Spennymoor to feed the blast furnaces, but it was iron and steel making that caused the population to boom.

Even when times were tough, like during the 1892 coal strike which caused the steelworks to fall idle, the management had enough faith in Spennymoor to invest in Europe’s largest “cogging mill” – a mill with two huge rollers that could turn the ingots into plates of steel 13ft wide.

And as it was hailed as Europe’s largest cogging mill, it may have been the world’s largest, also.

But it was a brief glimmer of the big time. By 1901, Spennymoor’s rural moorland location meant it was too distant to be economic, and steel production was transferred to Teesside. Hundreds of men were suddenly unemployed, although the gloom lifted in 1904 when the Dean and Chapter Colliery was sunk at Ferryhill – within a decade, it was employing nearly 3,000 men.

So for much of the 20th Century, Spennymoor had a largely redundant industrial site at its heart with the terraces of the former ironworkers fanned around it: (clockwise starting in the west) Spennymoor, Tudhoe Grange, Tudhoe, Mount Pleasant and Merrington Lane. Some industries tried to scratch a living, such as the cokeworks which operated into the 1950s, but the slagheaps stood tall as a reminder of the boom days which had turned to bust.

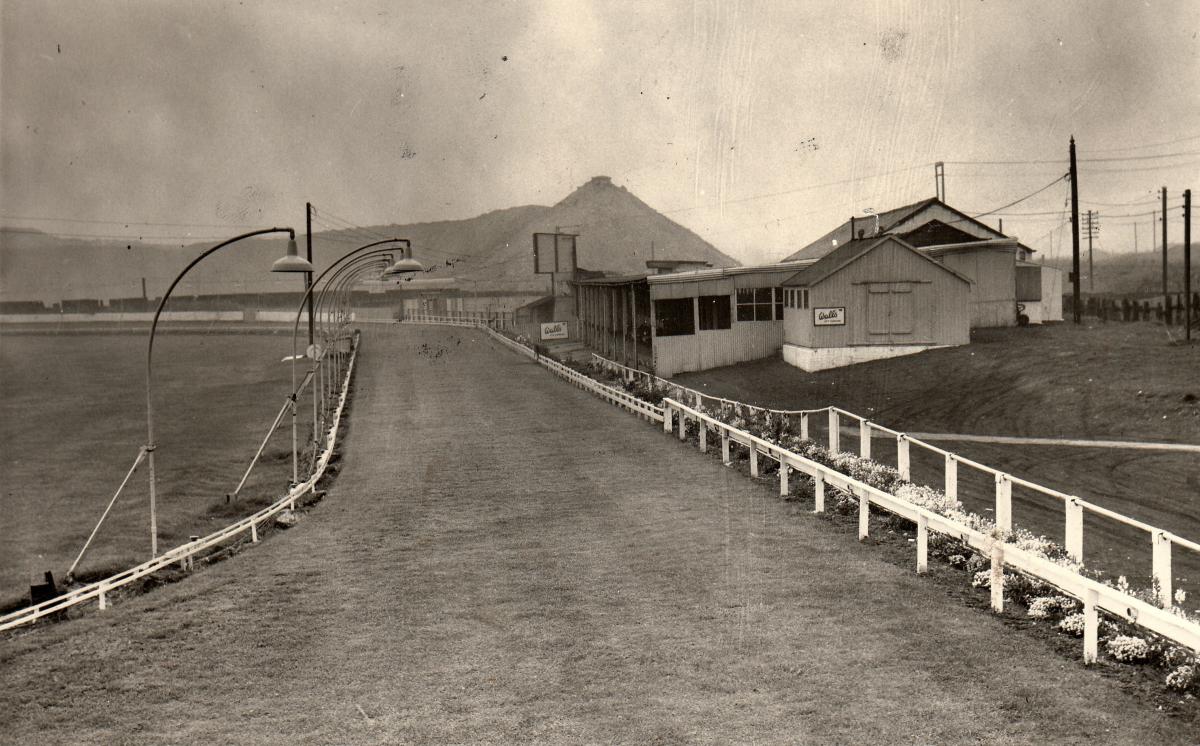

Even in 1950, when a greyhound stadium was established on the brickworks part of the ironworks site, the slagheaps were still clearly visible in the background.

And slagheaps should never be confused with pitheaps, which is exactly what Memories 390 did.

“They were slagheaps from the old ironworks,” says Frank Ripley. “As children we spent many happy hours scrambling about and getting covered in no doubt highly toxic dust, as well as watching the dog races for free.

“On the other side of the heaps was a pond where we used to sail our matchbox boats and, it was said, locals used to dispose of unwanted dogs and cats – although this may have been just a tale invented by mothers to try to stop us going in the water and getting drowned.”

Cllr Bob Fleming, the leader of Great Aycliffe Council, was born in Weardale Street in Spennymoor into a classic local family: his maternal side were ironworkers from Ironbridge in Shropshire and weavers from Somerset, and his paternal side were coalminers from Wales, all of whom were sucked into the boomtown in the 1860s.

“The slagheaps came very close to the houses in Bishops Close Street, where Norman Cornish was born near the railway, and to the Arcadia picturehouse, now a Wetherspoons, in Cheapside,” he says. “You could see that “First Slagheap”, as we called it, whenever you went out – it was part and parcel of life.”

Also part of the parcel of life were, as Frank Ripley said, the three reservoirs on the contaminated ironworks site.

“There was one which the cokeworks used, near the old tarbeds. I remember there were dead dogs in it, and a friend of mine fell through the ice there during the war and drowned,” says Cllr Fleming.

“The dogtrack was partly built on one that was called Chucky Dodgers pond. My grandfather said that a horse and cart, tipping rubbish into it, had gone in and the horse had drowned, and I remember in the 1940s, two children from Merrington Lane drowned there when they fell through the ice.”

The greyhound stadium was the start of a clean-up operation that took more than two decades to complete. Many of the ironworkers’ houses were cleared, with some of the residents moving to the new Bessemer Park Estate and others, like Cllr Fleming, going to Newton Aycliffe.

“I came when I was first married in 1959, and it was going to be for a year,” says Cllr Fleming, who is now the only living honorary freeman of the new town in which he has lived for nearly 60 years.

He still keeps in touch with Spennymoor and can still make out the outlines of the slagheap by the dogtrack, even though it closed in 1998 and more landscaping allowed houses and an industrial estate to be built on its site.

“There are still remnants of it,” he says, “although it looks like a green hill now, and someone has put a wooden hillfort on top of it as a children’s playground.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here