It is 150 years since a railway disaster's victims included the owners of a County Durham castle. Chris Lloyd reports.

“THERE is ample evidence of the destruction of 10 males and 13 females, and five whose sex cannot be detected,” reported the Darlington & Stockton Times 150 years ago.

“There is also further evidence of other bodies in the calcined dust, in the opinion of the medical gentlemen. The caps of all the skulls found are clearly taken off, as are also the thigh bones, which supports the theory that the sufferers were struck lifeless by the explosion.”

On August 20, 1868, a runaway train laden with highly inflammable paraffin oil smashed into the prestigious Irish Mail express, engulfing the wooden first class carriages in a ball of flame that was impossible to survive.

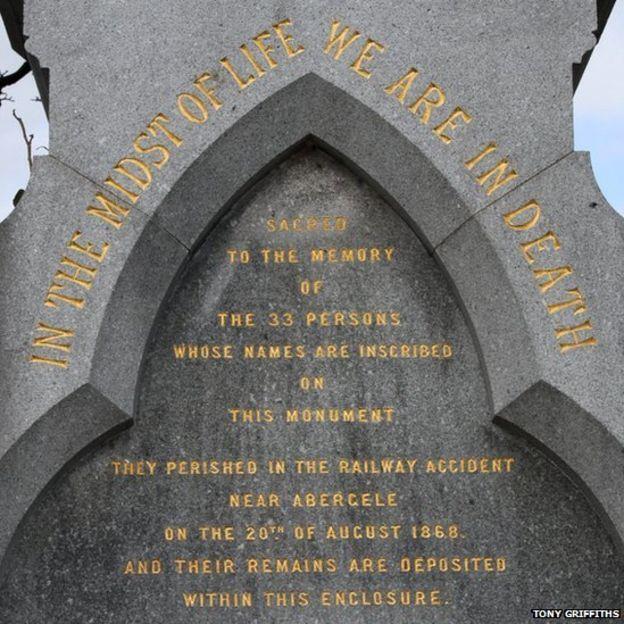

With a death toll of 33, it was then Britain’s worst railway disaster, and among the fatalities were the owner of a castle on the outskirts of Darlington, his wife and his eldest son.

It happened at Abergele, on the north Wales coast, and it deeply scarred the psyche of the nation.

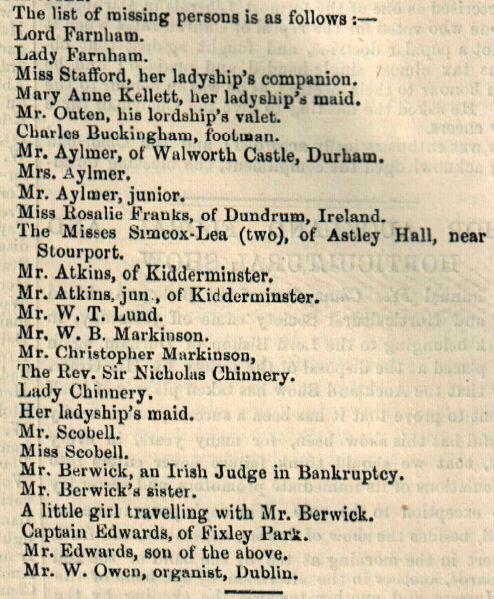

The Irish Mail was running from London Euston to Holyhead, pulled by one of the most powerful engines of the day, Prince of Wales. Part of its train was a Travelling Post Office, in which the Irish mail was being sorted, and it stopped at Chester to pick up more passengers, including John Harrison Aylmer, his wife Rosanna, and their 18-year-old son, John.

Their home was Walworth Castle. In fact, since Mr Aylmer had inherited the 16th Century castle in 1831, he had restored it and extended it so that he is really the creator of the hotel which stands there today.

They were travelling to Ireland because County Kildare had been the Aylmers ancestral home since the 12th Century, and Mr Aylmer’s elder brother, Sir Gerald, was the ninth baronet.

In front of the Irish Mail that day was a 43-wagon goods train that was due to pull into a seafront sidings at Llanddulas, just outside Abergele, to let the faster express past. But the sidings also served a lime quarry and there were already wagons parked up in it so there wasn’t room for the whole of the goods train.

With minutes to get out of the way before the express arrived, the Llanddulas stationmaster ordered that the goods train be broken up so that shorter lengths of it could be safely shunted into the sidings. This meant uncoupling and recoupling wagons as they stood on the mainline, and the bumping and barging of the operation caused the rear six wagons to break away and roll down an incline towards Abergele.

And the Irish Mail was just beginning its ascent of the incline at about 30mph.

And, to top it all, those last six wagons contained 50 barrels – about 1,700 gallons – of highly inflammable paraffin oil (a bit like today’s kerosene).

The driver of the Irish Mail, Arthur Thompson, saw the runaway wagons rolling towards him and knew a collision was inevitable.

“I should have stuck by the engine but I saw that some of the trucks had barrels of oil or something of that sort in them and I know the danger,” he told the D&S’ special correspondent who found him being treated afterwards in a cottage by the line. “I jumped off on to the bank. I called to my mate, Joseph Holman, the stoker, ‘Jump for your life, Joe’ and my mate did not do it.

“I fell on my feet and as I fell the engine caught the trucks. I was struck on the head by a fragment from the tender and half stunned.

“The moment after the collision the oil blasted up. It was all in an instant. I heard my mate give a groan and I saw him lying in a mass of flame, but none of the passengers stirred.”

The passengers, in their wooden carriages, didn’t have time to stir. The ball of flame was said to be at least 100ft high.

“It was not a fire but a furnace,” said the D&S, graphically. “The rails were of a white heat, the permanent way saturated with oil was red hot, the bank was in a blaze and the carriages, and everything and everyone in them, were consumed to dust.

“For hours this fearful spectacle was witnessed for the petroleum fed on itself long after the woodwork of the carriages had been destroyed. The spectators could plainly see for some time the skeletons of the passengers in the flames but before the fire was extinguished, skulls and legs and arms were calcined into dust.”

However, no witnesses heard any noises of terror from the victims, and the medical men believed that they were asphyxiated at the moment of impact when the explosion sucked all of the oxygen out of the air.

“There is a melancholy satisfaction in reflecting that this was so, that the unhappy victims were at least spared all torture and they were lifeless before the dreadful flames reached them,” said the D&S.

From all he jumped, driver Thompson was not the villain of the piece. In fact, he was a hero, because he helped uncouple the rear carriages of his train, including the mail vans, and pushing them away so they didn’t catch fire. Then he passed out through loss of blood.

“The collision was not a bad one,” he told the D&S’ reporter in the cottage. “It was the petroleum that did it all. If it had not been for that there would not have been a life lost.”

Such was the intensity of the blaze that only about ten of the bodies were identifiable. The bodies of Lord and Lady Farnham, for example, were recognised because Lady Farnham’s £6,000-worth of jewellery survived the flames.

The Aylmers don’t seem to have had that last dignity.

An inquest established who had been on the train, and a mass funeral was held in Abergele churchyard four days after the disaster. All the victims were buried together.

“When the mourners reached the huge grave they found there side by side, at a depth of some seven or eight feet, 32 coffins,” said the D&S Times of August 29, 1868. “There were the remains of 33 persons there for interment, but in one case so little had been left of a human body – only what had been gathered into a very small paper parcel – that the remains were put with those of another person.

“All the coffins were covered with black cloth, but there were no inscriptions. On the foot of each coffin was a bit of white paper bearing a number.”

The three Aylmers were laid to rest along with Mrs Aylmer’s Irish travelling companion, Miss Rosalie Franks.

The Aylmers’ family had bought Walworth Castle for £16,000 in 1775. The castle’s foundations date back to at least the 12th Century when it was the home of the Hansard family of barons. A medieval village grew up beside the Hansards’ fortified house, but it was deserted around the 14th Century, either due to the ferocity of Scottish raids or the Black Death.

In 1579, the Hansards’ estate was bought by Thomas Jenison, Queen Elizabeth's auditor-general, and his family substantially enlarged it, adding an enormous front that was certainly fit for a king when James I stayed there in 1603.

The upkeep of the castle eventually dragged the Jenisons down, and in 1775, it was sold to John Harrison, a Newcastle merchant for about £2.5m in today’s values. His daughter and heiress married into the Irish Aylmer family, and his grandson, John Harrison Aylmer, extensively reimagined the castle, including adding a north wing which blocked out the enormous front.

And it was John Harrison Aylmer who was killed at Abergele 150 years ago this month. As his wife and heir, who was just months away from starting at Trinity College Cambridge, died too, the property fell on his youngest sons who were not on the Irish Mail: Gerald, 12, and Edmund, nine.

Although wealthy enough – Gerald spent much of his life big game hunting in Africa – they never regarded the castle as home, and it was rented out to wealthy men. Queen Victoria’s financier, Sir Ernest Cassell, lived there, as did the Tyneside shipbuilder Sir Alfred Palmer and, in the early 1930s, Mr Dodge, a millionaire American car manufacturer.

During the Second World War, the case was used for military purposes and then it was sold to Durham County Council as a residential school for girls with learning difficulties. In 1980 it was sold to become a hotel, which opened in 1982.

But 150 years ago, the news of the terrible tragedy at Abergele was just sinking in at Walworth. A special service was held at Heighington church which had been intimately connected with the castle since the days of the Hansards and which the Aylmers attended regularly.

“Their philanthropic actions, amiability and kindly dispositions endeared them to all who knew them,” the Reverend W Beckett told the packed church.

“He said if anything could give comfort to this deeply stricken family, it was the firm belief that those they now mourned were singing the praises of God in heaven,” said the D&S Times. “At this portion of his address, the reverend gentleman’s feelings quite overcame him, and it was a considerable time before he could resume his discourse.

“The scene was deeply affecting as scarcely one in that vast assembly but gave way to an outburst of genuine grief.”

The article concluded: “The pulpit and pews belonging to Walworth Castle were draped with black cloth.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel