GERTRUDE BELL is probably the most remarkable woman to emerge from the Tees Valley and her amazing life is to be commemorated next weekend in her adopted village of East Rounton, between Northallerton and Darlington.

By coincidence, she will also feature in an illustrated talk to be given at Darlington’s Festival of Ingenuity next Saturday which commemorates the 100th anniversary of women getting the vote.

However, while Gertrude spent most of her life as a pioneering woman creating history around the world, when it came to women’s suffrage, she was on the wrong side of history.

Gertrude was born in 1868 in Washington Hall, in the north of County Durham, which was the home of her grandfather, Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell. His works produced a third of Britain’s steel, could make everything from a needle to a ship, and employed about 47,000 men.

The Bells were the sixth richest family in England, and Gertrude grew up at Red Barns, a mansion near Redcar, as her father, Sir Hugh, ran the Teesside steelworks and was thrice mayor of Middlesbrough.

In 1870, Sir Isaac had a very fashionable Arts and Crafts mansion, Rounton Grange, built between Northallerton and the A19. It had 39 bedrooms and one bathroom (he only allowed the modern convenience to be added after much pressure from his family), and Gertrude later designed its grounds.

Landscape gardening was just one of her many talents.

She was the first woman to receive a first class degree in Modern History from Oxford University. She was the first person to climb all the peaks in the Engelhorner range in the Swiss Alps where she still has a mountain – the Gertrudespitz – named after her.

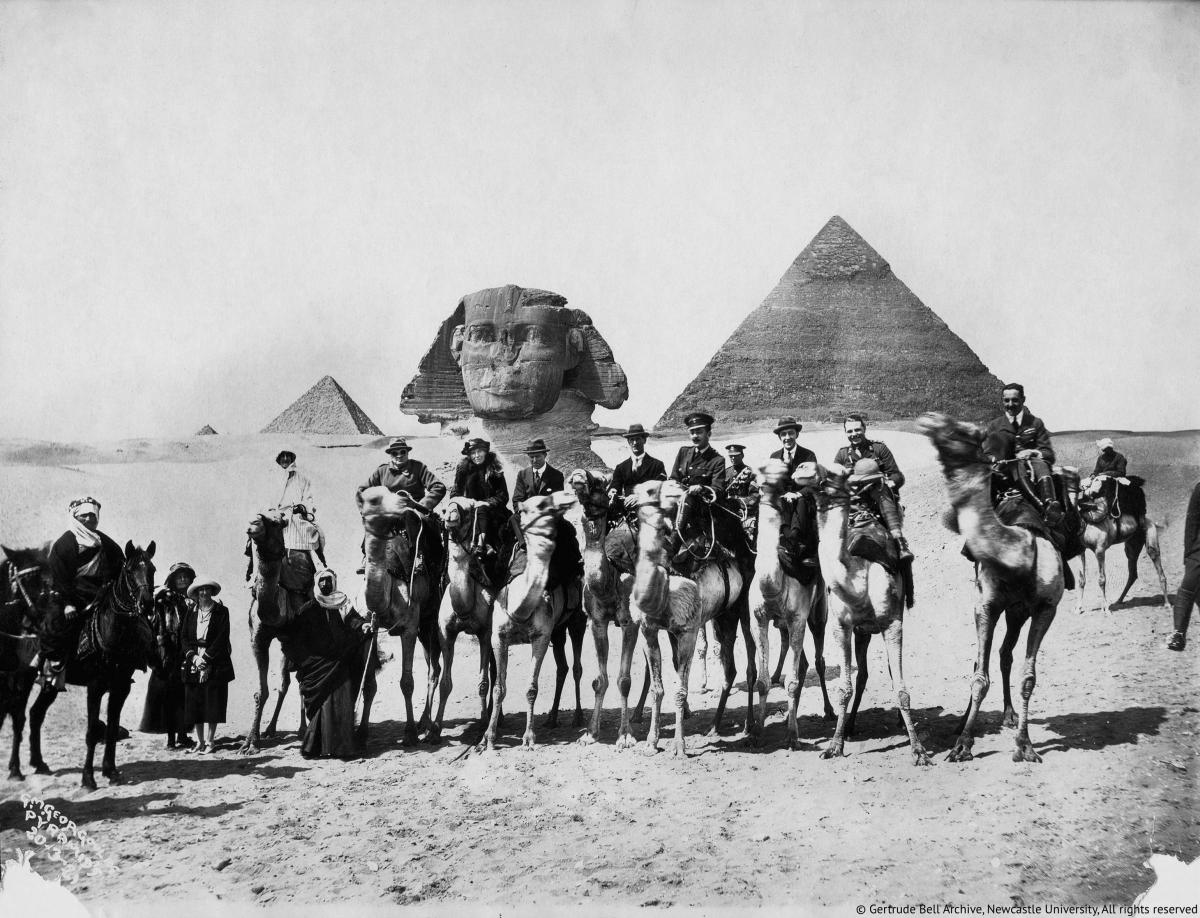

She was the first woman to do a solo journey into the uncharted Arabian desert – having learned to ride horses on Redcar beach, she rode 1,500 miles on a camel.

She was the first female Intelligence officer – the first woman spy – to be employed by the British military, but the Arabs upon whom she was spying regarded her so highly they called her the “Mother of the Faithful”.

She was a close advisor to Winston Churchill and, at the time of the First World War, she was the most powerful woman in the British Empire.

She is the only woman from our area to create a country: she drew up the boundaries of Iraq, wrote its constitution and installed its first king, Faisal, who made her the new nation’s first Director of Antiquities.

Hers is an utterly extraordinary life (even her death is still debated as she passed away in Baghdad on the night of July 11/12, 1926, having taken an overdose of sleeping tablets). She should be a feminist icon.

And yet, even though she campaigned for women to be more involved in health services and schools, she didn’t want them to have the vote. Even though she campaigned for the rights of Muslim women in Iraq, who she found were forced to spend most of their time indoors, she didn’t want British women to have equal votes.

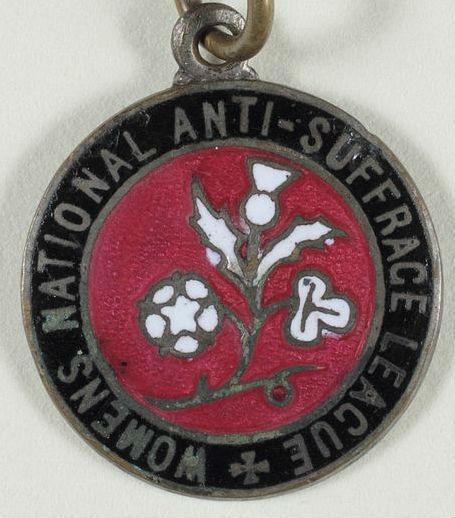

In 1908, just as the suffragettes were rising to prominence, Gertrude was a founder member of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League, and she became president of its northern section. She wrote to The Times newspaper denouncing “the extraordinary and regrettable programme” of the suffragettes, and in 1909 she organised a petition, signed by 250,000 people, demanding that women should not get the vote.

Gertrude wrote in her diary about how she loved to get on a train in London, strike up conversation with a woman sitting beside her and then try and covert her to the anti-suffragist cause by the time Darlington was reached.

Gertrude had many reasons for her views. She thought that giving women the vote would turn the proper male-dominated order of society on its head; it would destabilise the country and weaken the British Empire.

She thought giving women the vote would distract them from their principal role at the heart of the family. She felt it would prevent them for volunteering their time in schools and community organisations so their role in society would be diminished.

And she deplored the violence of the suffragettes who were throwing stones, setting fire to buildings, slashing paintings and debagging men – they were the terrorists of their day.

Some biographers try to say she was only briefly involved in this cause, but as late as November 1912, Gertrude was organising an anti-suffrage meeting in Middlesbrough.

Gertrude’s many and great achievements should be celebrated, and they are magnified by the fact that she was a woman breaking down barriers in a variety of places across what was then a man’s man’s man’s world. But when it came to voting, she seems not to have wanted to give other women a hand up.

NEXT WEEKEND, East Rounton is celebrating the publication of a book entitled BEZIQUE: The Private Life of Gertrude Bell, written by Dr Graham Best. There is a free exhibition in the village hall from 10.30am to 4pm on Saturday, July 14, and from 10am to 2pm on Sunday. On Saturday at 7pm, Dr Best and Jan Long are giving an illustrated lecture, The Fascinating Gertrude Bell.

Gertrude will also appear in a free talk given by Chris Lloyd, who compiles Memories, as part of the Darlington Festival of Ingenuity, on Saturday, July 14, at 1pm. It is entitled Screechers and Suffragettes: Darlington’s Role in Votes for Women, and will take place in Central Hall.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here