THE waters are a bit whiffy. A bit eggy. A bit farty. But those that come gushing out of the ground in Croft-on-Tees can do you good.

For a start, they can miraculously cure your health problems.

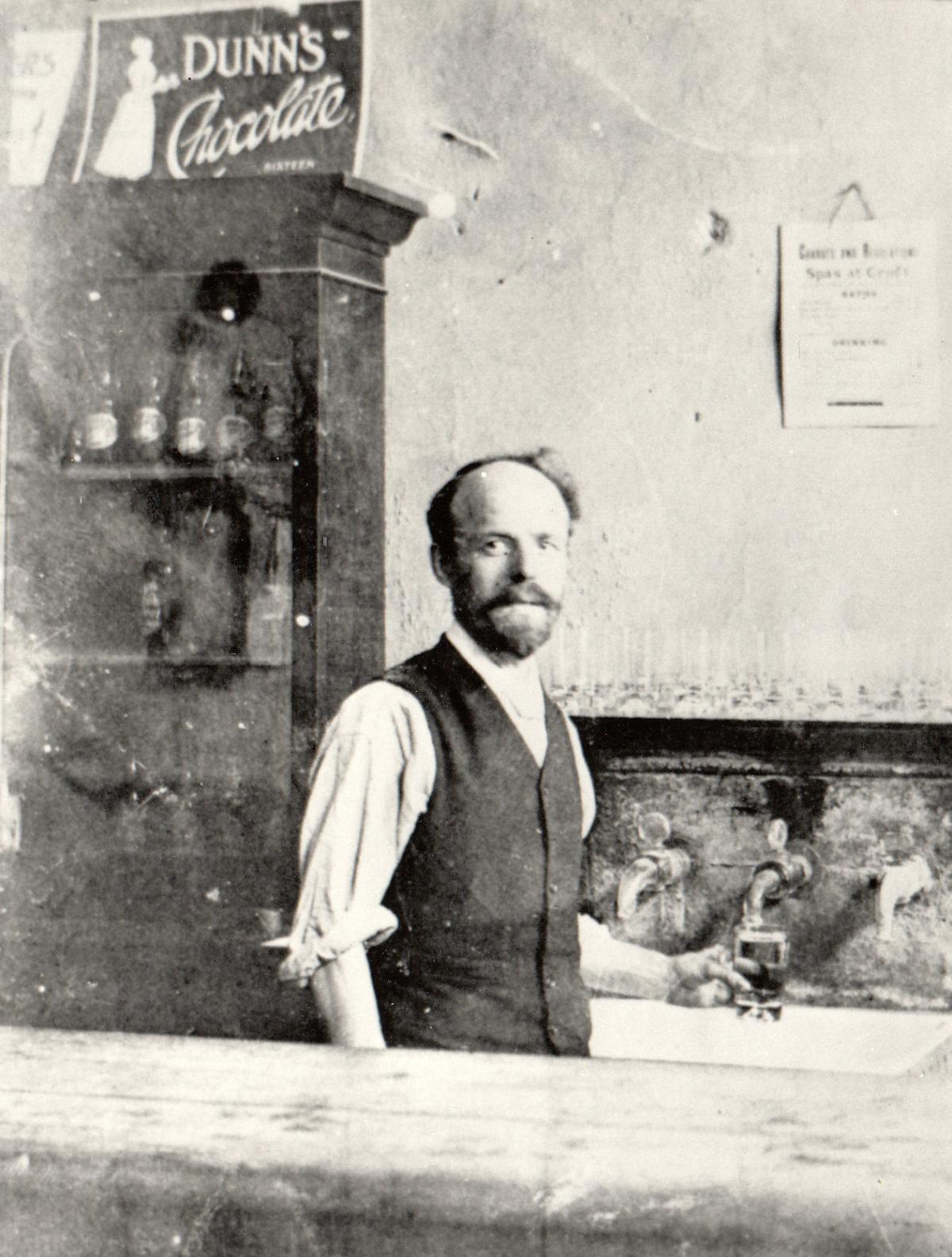

“The sulphur water should be drunk shortly before meals, one half-pint at a time being the quantity prescribed by doctors,” says a 1907 guide to the village which is in the northernmost corner of North Yorkshire. “This should be repeated two or three times a day, when in a short space of time, the drinker ought to feel like ‘a giant refreshed’.”

The waters might even inspire you to become the world’s greatest children’s author. It is no coincidence that Croft, to the south of Darlington, was the family home of Lewis Carroll from 1843 to 1868, when the spa trade was at its height. It must have inspired one of the central themes of Alice in Wonderland: when Alice tumbles down the rabbit hole, she finds a bottle with a label saying “drink me” on it; when she does, the waters do miraculous things to her body – she even grows until she looks like ‘a giant refreshed’.

Today, the wells are overgrown on private property, but next Sunday, there’s a guided walk looking at the village history and, hopefully, visiting a couple of the whiffy watering holes.

Until 1669, Croft was known by the nickname of “The Stinking Pitts” because of the sulphurous, eggy water that came belching out of the ground. But then someone noticed that horses and dogs that stood in the stinky mires were cured of skin complaints and swollen joints.

Sir William dug a horsepond for his animals to bathe in, and when the condition of his thoroughbreds improved, humans started turning up to try the water.

In fact, so many came to splosh around hideously naked in the boggy fields that Sir William Chaytor, whose family had owned a large estate at Croft since the 13th Century, erected a building, with a 4ft deep plunge pool, in which visitors could disport with a modicum of decorum.

Soon the Croft waters were being hailed as most efficacious in every way. They cured everything: scrofula, diabetes, rickets, blindness, paralysis and TB as well as skin complaints. Even Sir William Bowes of Streatlam Castle testified that he was “violently troubled with the jaundice” until the waters of Croft got him moving.

For Sir William Chaytor, this had the potential to offer a great boon because he spent most of his life in dire financial straits.

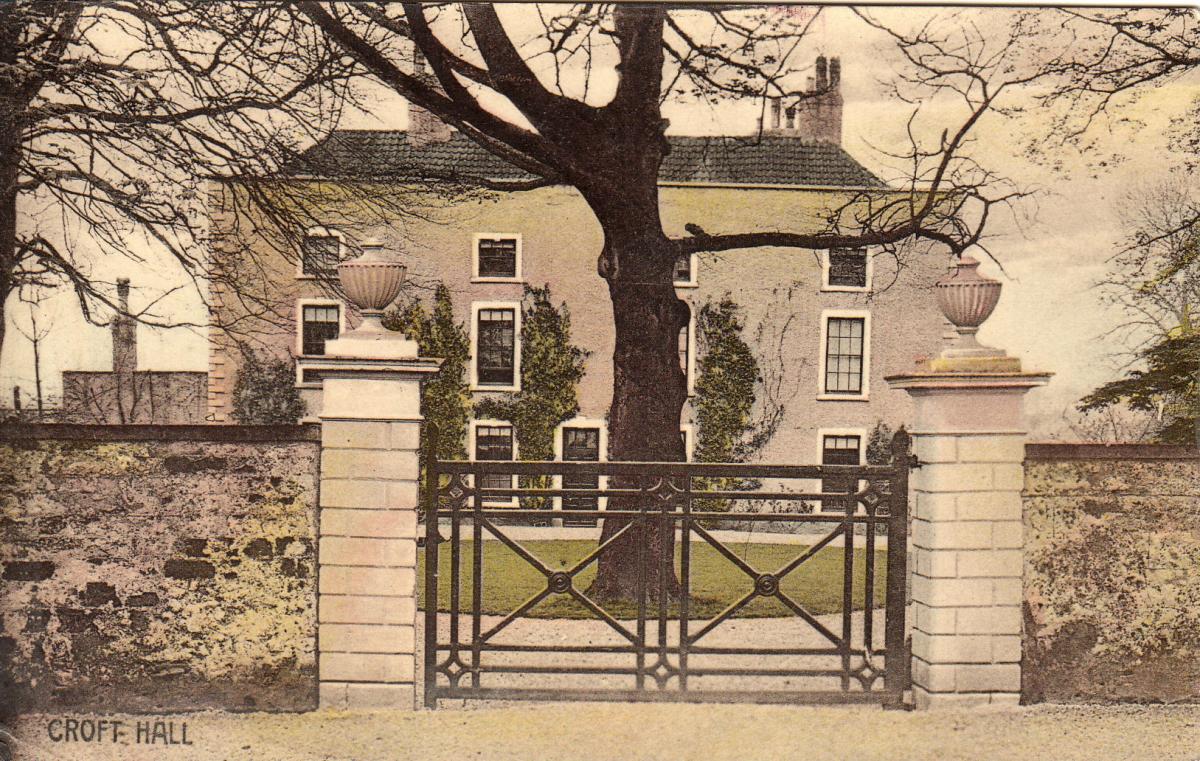

He had inherited the Croft estate in 1664 from his second cousin, Colonel Henry Chaytor. However, the colonel’s sister, Agnes, contested his will. She was married to Sir Francis Liddell of Bamburgh Castle and Redheugh. Sir Frances had been a major in the Royalist army during the Civil War and he assisted his wife’s cause in a military manner.

He hired a gang of colliers in Newcastle, dressed them as soldiers and pretended to march them to Hull.

Instead, they stopped off at Croft and seized Croft Hall, the Chaytor family seat.

Sir William and his father, Nicholas, had to crawl in to the hall through a cellar window to regain possession and to regrasp his inheritance.

Just as Sir William thought things had settled down, his father, Nicholas, died in 1655, and his sister, Anne, contested that will. The courts eventually decided that Sir William should pay Anne a £500 annuity (worth £115,000 in today’s values).

But Sir William couldn’t afford to pay Anne, so in January 1700, he was arrested at Croft and dragged off to Fleet, the London debtors’ prison made famous by Charles Dickens in Pickwick Papers.

From his cell, Sir William tried to get his affairs in order, even pawning his own gold wedding ring. Monetarising his whiffy waters was an obvious idea, and by 1713, bottled Croft water was on sale at the fashionable Golden Key in Ludgate Hill, London.

The waters were not, though, efficacious enough to cure Sir William’s bank balance, and he died in the debtors’ prison in 1720.

His grandson, another Sir William, was one of the early promoters of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) – he wanted to exploit the coal around his Witton Castle estate, near Bishop Auckland.

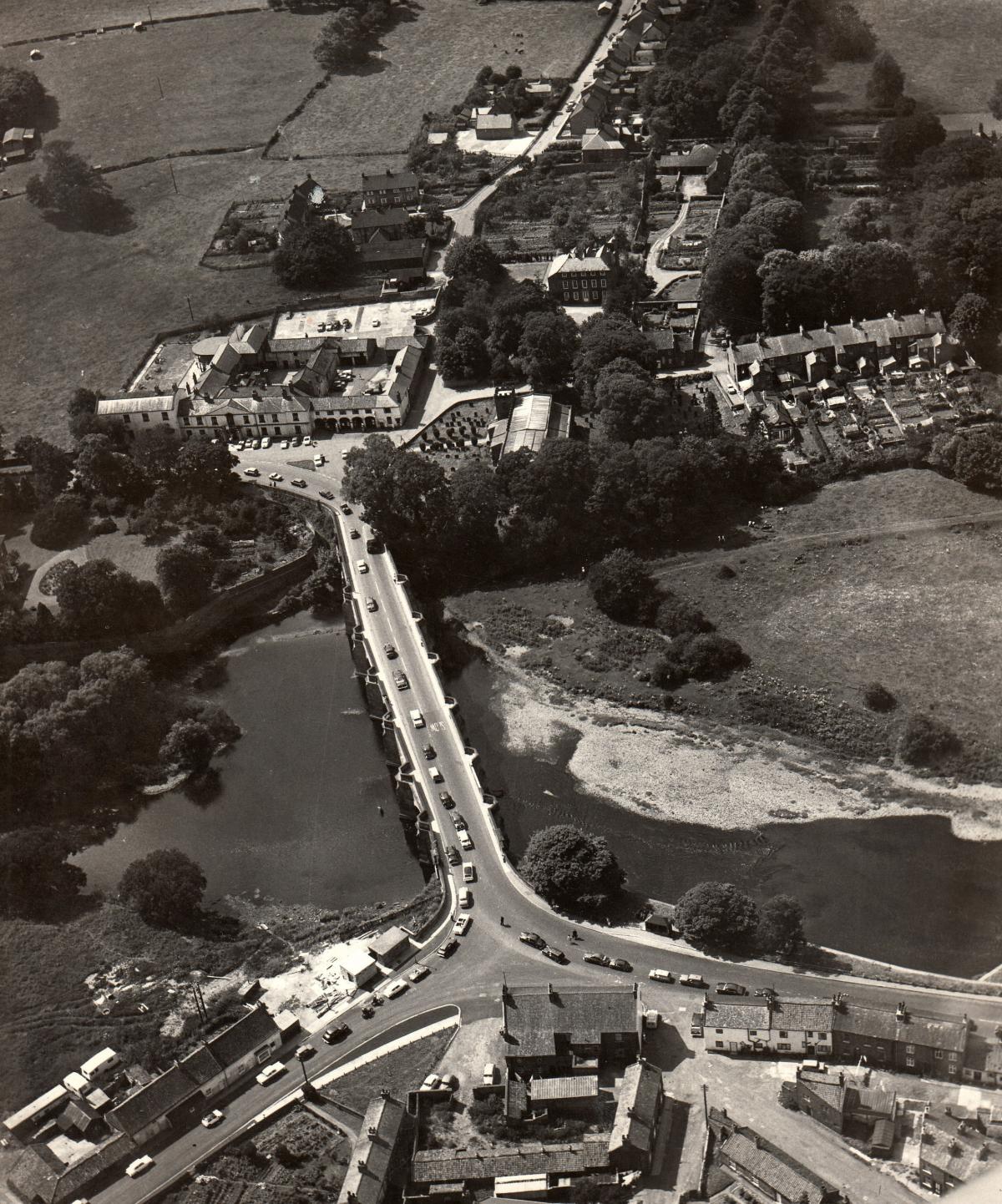

He too wanted to exploit his whiffy waters – a new spring, called Canny Well, had been found and it and the Old Spa were attracting many people, so in 1808 he built a hotel by Croft bridge.

He then began boring to find a stronger supply of water. In 1826, he struck lucky: 26 fathoms down (that’s 156ft or 47.5 metres) he punctured an aquifer which caused sent up such a high pressured spurt that the drilling rig was blown out of the ground.

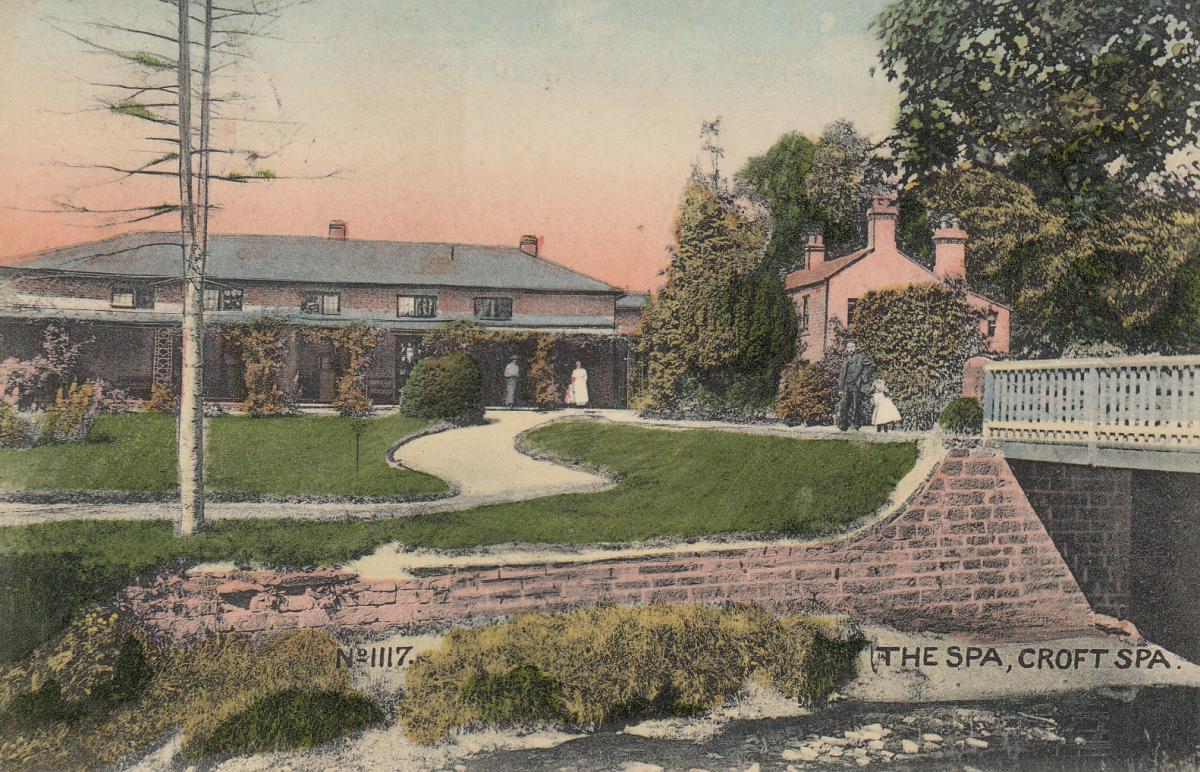

By happy coincidence, this water, of which there was an endless supply, was found to be even more efficacious than that in the Old Spa, so Sir William built the New Spa buildings over the top.

It was an early health resort: you could bathe in the heated spa waters, you could drink them as prescribed, and you could wander through the woods – floodlit by fairylights – to find the other wells.

“The walk through the wood to Canny Well and the Old Spa appears to be the greatest favourite,” wrote a visitor in 1866. “It is certainly an enchanting walk for any part of the day; the soft warbling of the birds, and the gentle murmuring of the brook, are enough to banish ennui and create a forgetfulness of pain.”

In 1829, the S&DR opened one of its first branchlines into Hurworth Place on the opposite bank of the Tees to Croft. The railway was supposed to carry coal to Yorkshire, but it also brought spa guests to Croft. There were so many that in 1835, Sir William had Ignatius Bonomi, Durham’s greatest architect of the era, enlarge the Croft Spa Hotel, and in 1837, 800 bathers visited the village.

When the first stretch of mainline between York and Darlington came rumbling through the area in 1841, the station in Hurworth Place was called “Croft Spa” to attract more visitors, and in the 1860s, terraces of townhouses were built around Lewis Carroll’s childhood rectory to accommodate those who came for the season.

That, though, was the high point of fashionable Croft, and after the First World War, the spa trade fell into terminal decline.

The New Spa was demolished in 1967 and the woodland walks have become lost – although there are still a couple of gurgly wells that bring the whiffy waters to the surface, if you know where to look.

And remember:

“If you don’t drink spa water

You’ll die afore you oughter.”

- On Sunday, July 1, Chris Lloyd is leading a guided walk through historic Croft to raise funds for the rebuilding of the village hall. Part one starts at 1pm at the village hall and is a 90 minute ramble on the flat around the village. Part two is tea and cake in the village hall before part three, another walk, heads off across country at about 3.15pm in search of a spa or two. The parts are £3 each, or the whole Walk in Wonderland is £8. To reserve a place, and to help with cake numbers, please email susan1.coates@yahoo.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here