SHORTLY after midnight 100 years ago on Monday, with his ship heaving violently and enemy fire washing his decks, Lieutenant-Commander GN Bradford made the split second decision that became the defining moment of his life.

Indeed, of his death.

He jumped.

Last Saturday, the centenary of his jump was commemorated in his birthplace of Witton Park, near Bishop Auckland, with the unveiling of a special stone which goes to the home of every First World War Victoria Cross winner.

Bradford won his when he was in command of Iris II, one of three advance ships leading a daring cross-Channel raid of 75 ships and 1,700 men. The object of the raid was to sink three blockships, filled with cement, across Zeebrugge harbour so it could no longer be used by enemy submarines.

But the harbour – a manmade mole – was defended by German gun emplacements. Before the blockships could be manoeuvred into place, the guns would have to be taken out, and that required the advance ships to sail up to the 30ft high harbour wall and land hundreds of soldiers who could attack the guns.

The British approached Zeebrugge under the cover of a manufactured smokescreen, but when the three advance ships – Iris II and Daffodil, both former Mersey ferryboats, and an old cruiser, HMS Vindictive – were about a quarter of a mile out, the breeze swung round, and blew the smoke out to see, leaving them naked in the enemy gunsights.

This mini-armada had already set out twice from England in previous weeks only to be forced to return as the weather deteriorated. Now, so close, there was no mood for turning back, so instead, the three advance ships rushed towards the harbour wall, attracting intense fire as they went.

As they sped in, their motion, and the squally weather, whipped up large waves which slapped against the wall.

The soldiers on deck placed their landing ladders against the wall, but the surge of the swell snapped them like firewood.

Lt-Cmdr George Nicholson Bradford could see that the operation was doomed unless his ship could somehow be tied to the harbour so the men could get ashore.

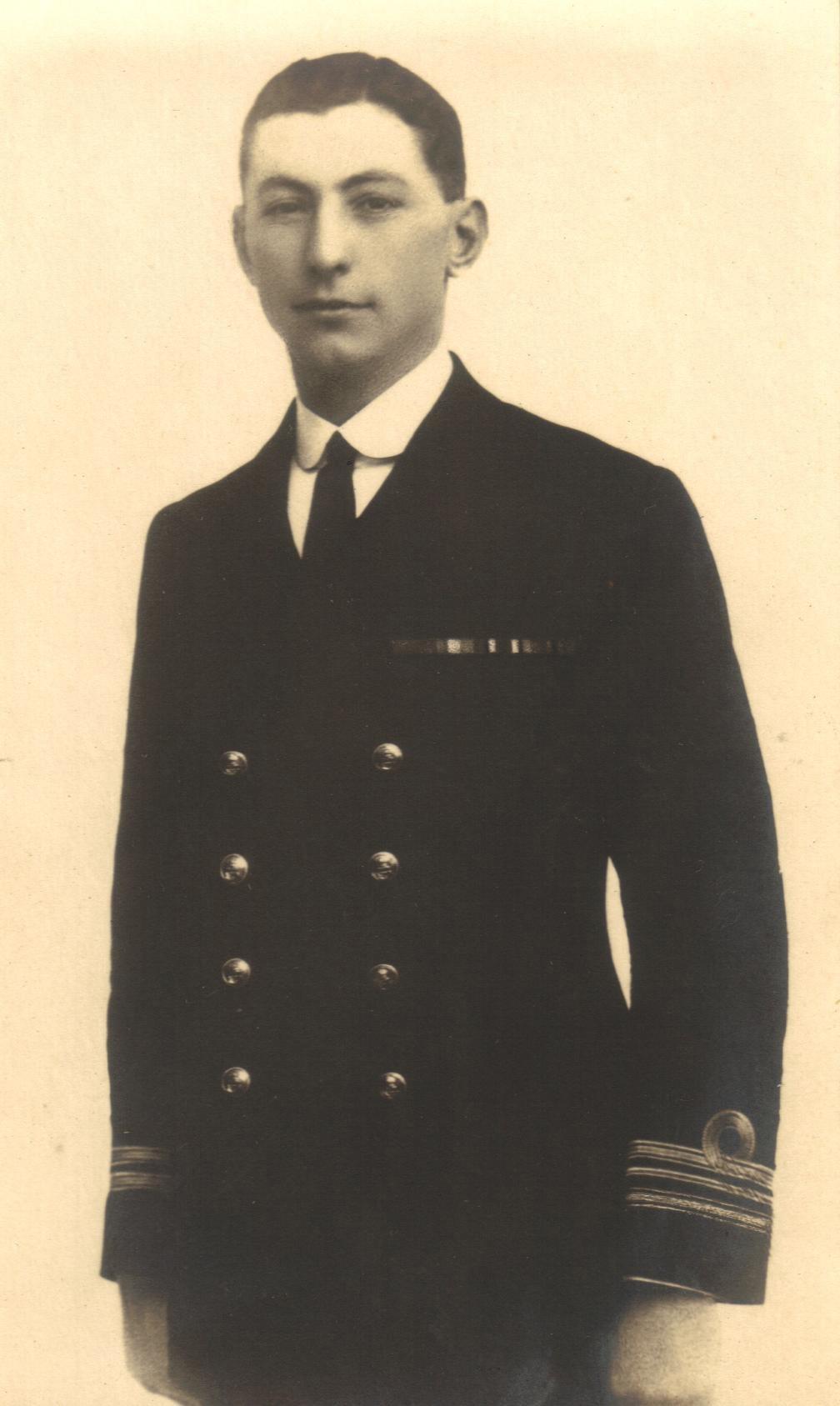

It was 31 years to the day that Bradford had been born in Witton Park, the son of a colliery manager. He’d grown up in Milbank Road, Darlington, attending first Bondgate School and then Queen Elizabeth Grammar School. He had joined the Royal Navy in 1902, perhaps to escape his tyrannical father.

He had already exhibited remarkable braveness. In 1908, he’d rowed a lifeboat for 15 minutes on a dark night in the English Channel to rescue three men from a sinking trawler which had been struck by a warship. After his return, he discovered there had been a fourth person on board, a young boy, so he rowed back out, climbed aboard, disappeared into the dark of the hold and re-emerged with the unconscious boy on his back.

Just as he tipped the boy and himself into the little lifeboat, the trawler had slumped beneath the waves.

What he did on April 23, 1918, was even more remarkable. Iris II had a derrick, or crane, fixed to its deck which reached high into the midnight sky – and up into the gunfire. Bradford conceived his plan.

With the ship pitching terribly in the waves, and the top of the derrick smashing against the harbour wall, he picked up a parapet anchor and climbed to the top of the crane.

That in itself was an athletic achievement, but then he waited for the right moment. The derrick swayed violently and the shells rained down, but he waited until a wave lifted the Iris II up so the top of the crane was practically level with the top of the harbour wall.

Then he jumped.

He landed, as he planned, on top of the wall and triumphantly secured his anchor.

But in the split same second, as he must have known, the wave passed. Iris II dropped out of view, leaving him utterly alone, without any prospect of protection, on top of the harbour. Every German gunner naturally trained his sights upon this vulnerable figure.

One account says he survived three minutes in the line of fire, busily securing the grappling iron and tying on ropes, while being buffeted by bullets.

The citation for his Victoria Cross says: “Immediately after hooking on the parapet anchor, Lt Cmdr Bradford was riddled with bullets from machine guns and fell into the sea between the mole and the ship.”

Petty Officer Michael Hallihan, an Irishman, saw him fall and dived in to rescue him. He, too, perished.

The citation concludes: “Lt-Cmdr Bradford’s action was one of absolute self-sacrifice; without a moment’s hesitation, he went to certain death, recognising in such action lay the only possible chance of securing Iris II and enabling her storming parties to land.”

Those parties did indeed land. They took out the gun emplacements. A couple of old British submarines, filled with explosives, were then detonated against the mole, and the three blockships were guided into place and successfully scuttled.

Zeebrugge harbour was at the mouth of an eight-mile canal which began inland at Bruges. German U-boats would sneak out of the canal, play havoc with British shipping in the English Channel, and then sail back down the canal to Bruges where they were so far away from British guns as to be safe. Scuttling the blockships was to prevent the U-boats using the canal as a haven.

Whether it did or not depends on whose propaganda you believe. For the British, it was an enormous victory won by tub-thumping, chest-beating derring-do. Eight Victoria Crosses – the highest award for military bravery – were dished out.

Here we reproduce The Northern Echo’s front page of April 24, 1918, which was published before the heroics of the local lad were known. It hails the bravery of the men from the three ships who landed on the mole, and it includes a rapidly-issued statement from the king himself. He said: “The splendid gallantry displayed by all, under exceptionally hazardous circumstances, fills me with pride and admiration.”

After an hour of carnage, the battered wreckage of the three ships tried to sail away from the damaged harbour. “Vindictive’s deck presented a terrible sight,” a survivor told the Echo. “The upper decks were slippery with blood, and all around lay dead, dying and wounded.”

Under cover of another smokescreen, they made it back to Dover at 8.30am, where they received “a splendid ovation”.

The British had lost 227 dead with 356 wounded and one ship – HMS North Star – sunk. The indisputable heroics of men like Bradford restored the British public’s faith in their much-vaunted Royal Navy, which had been frustratingly inactive for much of the war.

But in the raid, the Germans had only lost eight dead, ten wounded and, if the truth be told, their operations out of the harbour were only mildly inconvenienced by having three bits of British scrap lying around.

Bradford’s body was washed up on a beach two miles from Zeebrugge at Blankenberge a couple of days later. The Germans buried it with full military honours.

Nearly a year later, his mother, Amy, went to Buckingham Palace to collect his medal. It is supposed to have been her third visit. She had gone down to collect the Military Cross for her 28-year-old son, James, who had died a couple of months after being awarded it in March 1917; she may well have be present when her 25-year-old son, Roland, had been presented with his Victoria Cross in June 1917 – he had been killed a couple of months later.

It is said that when King George V spotted her for a third time, he roared: “What! You here again!”

Of course, Roland and George are the only brothers to be awarded VCs during the First World War. Roland won his VC for his supreme bravery and leadership on the Somme, and his award was commemorated on his centenary in October 2016.

Last Saturday it was George’s turn – and it must be worth a moment to think of the extraordinary, self-sacrificing split second when he decided to jump.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel