Second World War veteran Harry Oliver is to be guest of honour at Durham Cathedral’s Festival of Remembrance Concert later this month. He told Gavin Engelbrecht his remarkable story

"I JUST went numb", recalls Harry Oliver about the moment he was captured and made a prisoner of war. His first thoughts were of the sweetheart he had left only months before to go to battle with the Durham Light Infantry.

The 98-year-old veteran's war was brought to an abrupt ending in May 1940 when a French farmer found him hiding in a barn and handed him over to a German tank regiment.

During next five years, Mr Oliver would endure starvation and lice, worked in salt mines and stone quarries, escaped twice, was bayoneted by a guard and forced on a death march of 400 miles in 33 days, before his eventual freedom.

Mr Oliver of Sherburn Village, near Durham, shared some of his vivid memories as he prepares to be guest of honour at Durham Cathedral’s Festival of Remembrance Concert.

A miner at Bowburn Colliery before he enlisted with the 10th DLI at the outbreak of war, he almost immediately found himself at the frontline.

He says: “I remember them calling for two volunteers to man a Bren gun on a bridge. Nobody came forward at first. At the third time of asking, my friend and I put our hands up thinking that we were going to be together. But no, the sergeant dropped me off at one place and took him onto another.

"He got back to the regiment that day, I didn’t.”

Instead, finding himself “in the bag”, Mr Oliver was forced on a 250-mile march through France, Belgium and Luxembourg to Trier, in Germany, where prisoners were crammed into cattle trucks for the long journey to Thorn (now Torun), in Poland.

He says: “It was a different situation to what any of us had ever been in before. After the initial shock of being taken prisoner there was the food problem.

“Several thousand of us were kept in marquee at the first camp, sleeping on the ground in our clothes. The majority of us spend a lot of our time with our trousers off taking lice out of the seams. It was terrible.”

Mr Oliver later found himself at a salt mine, where he loaded bags of salt onto trucks.

By September 1942, he had “had enough” and hatched plans for his first escape. Interested in the destination of the salt they were loading, he noticed some of the bags were going to Ireland.

“I thought the only way it could get there was through Spain and decided to go to Ireland. I said to my Scottish friend Adam Erskine “I feel like having a go at this, are you? "He said yes. We never told anybody else.

“On a late shift, a Polish man I knew was loading a truck. No words passed and we got in and hid away. I knew the procedure was the train would come and load the trucks. I didn’t realise it was going to go so well. We knew we were well on the way when I could see out of a little slot that we were passing through Koblenz."

Then, stopped in a station for three days and dehydrating, they broke their cover to try and get water, only to get caught.

Mr Oliver says: "When I saw the sign at the station I burst out laughing. My captors asked me what was so funny. We were back in Trier, where I had first set off on a transport to Poland all those years ago."

In March 1945, Mr Oliver was in east Germany when the advancing Russians neared their camp.

He says: "There were 140 of us in the camp and seven in our hut. On Good Friday I said to the lads “I don't know what you're doing but I'm packing”. So we packed up. The next day guards came in and said to pack up we leaving in an hour. We were already packed.

"When we got outside the camp and had to wait several hours because Russian shells continued to come over us. But when we did start that was the start of 33 days forced marching and that took us up to May 4 when the guards eventually left us. We were about 40km east of Munich. It was a beautiful morning. I remember you could see the snow in the Alps. It was a wonderful sight. And we were free.”

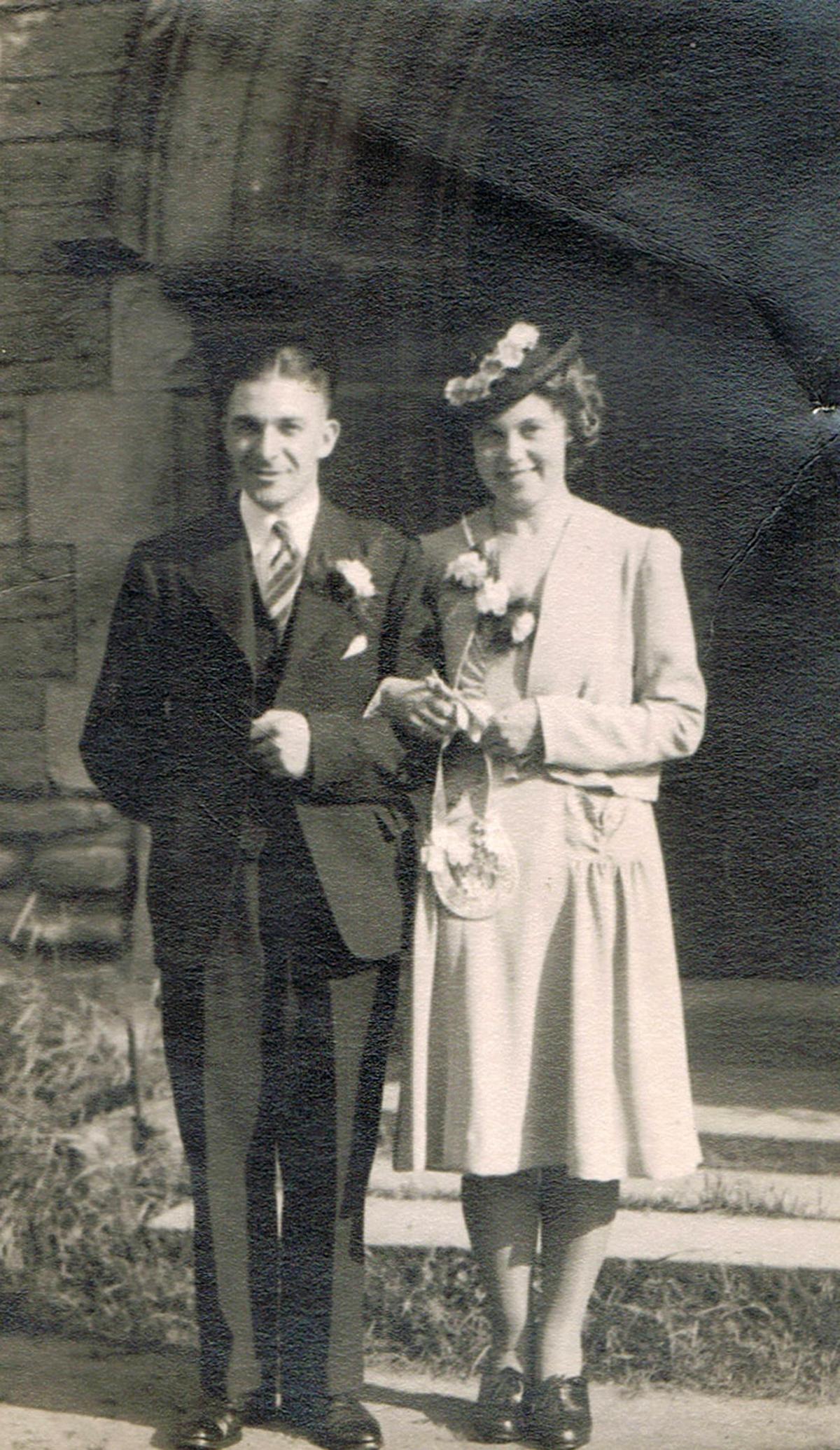

The day he returned home, his sweetheart, Margaret "Peggy" Middleton, was at his mother's home to greet him. Three weeks later, on June 21, 1945, they got married. His good suit hung on him as he had lost so much weight. His wedding suit belonged to Arthur, Margaret's brother, who was killed aged 21.

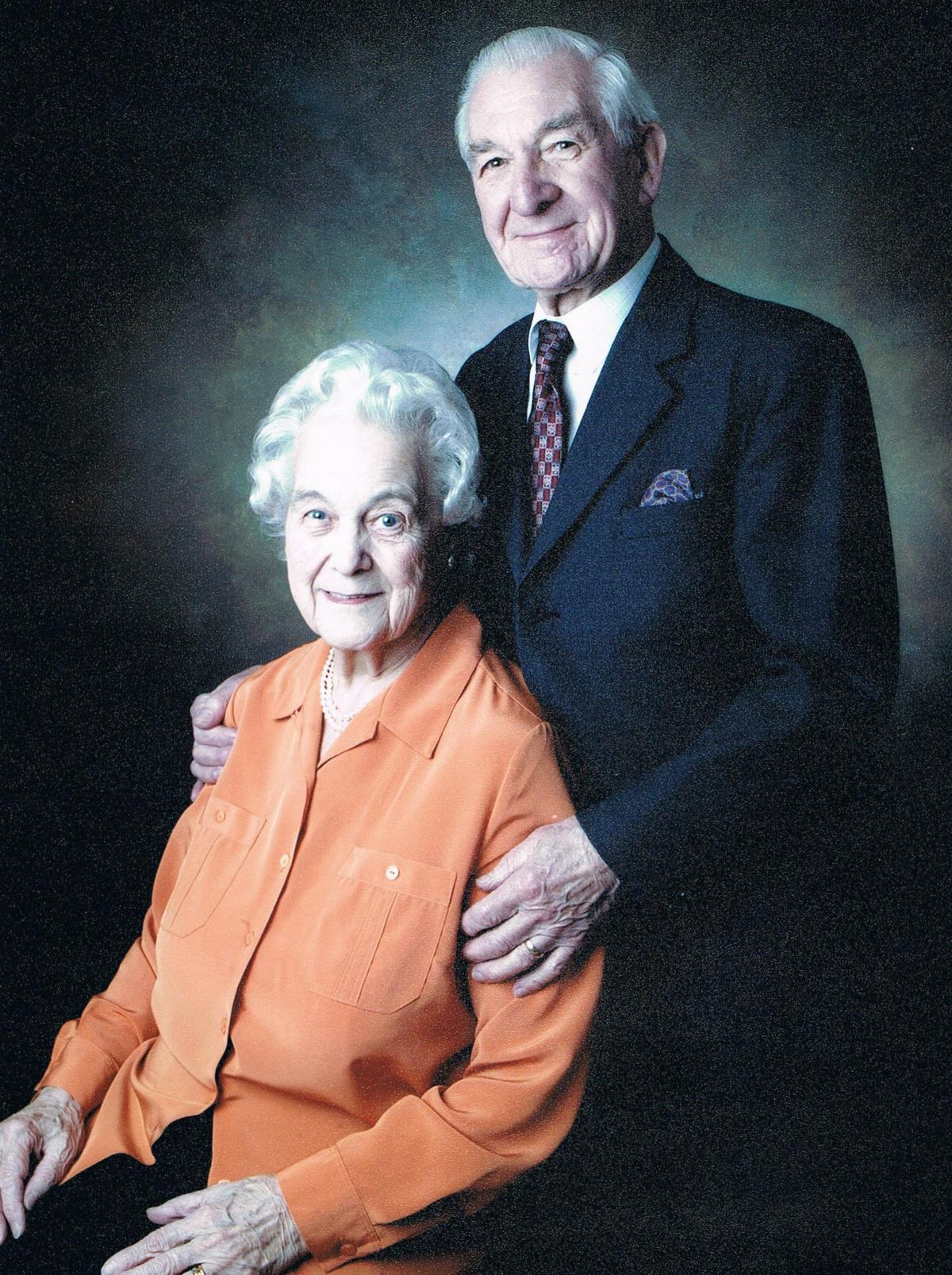

Mr Oliver adds: “I still think of all the lads who didn't come home. I've had a good life. My wife died four years ago in our 68th year of marriage. In total we were together for 74 years."

Writing in his memoir, he says: “Looking back now I think of all those wasted years.

"I think of the friends I made and lost. I think of the hunger and cold. I think too of those terrible marches and the things I saw, but through it all the thought of my dear Margaret sustained me. I never doubted she would be there, good and true, and for that and for her love of more than seventy years I am truly blessed and eternally grateful.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel