WHEN the soldiers of the Durham Pals were roused from their beds at 4.30am and issued with 160 rounds of live ammunition, it was obvious that this would not be another drill.

Dug into their trenches on the coast at Hartlepool, they peered out to sea towards an unseen enemy, shrouded by thick mist and the December dark.

For several hours, the former teachers, clerks and shopworkers of the newly-formed 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry stood armed and ready to repel the expected imminent invasion of their home county.

When the first shellfire broke the silence at around 8am, it only added to the confusion as a small British flotilla and German battlecruiser squadron fought a short, sharp engagement out of sight of the coast before, suddenly, the enemy battleships Seydlitz, Moltke and Blucher emerged from the mist just one-and-a-half miles off Hartlepool and opened fire on the town.

One of the first shells landed near the Heugh Battery and killed four of the Durham Pals, earning the battalion an unwanted place in history: the first British soldiers to die at the hands of a foreign enemy on English soil in almost 250 years.

THE battalion had been at its Cocken Hall headquarters, near Durham, when it received orders on November 16 to reinforce the coastal defences at Hartlepool. It should have been a straightforward mission for the Pals, formed only months earlier and still in training.

Two companies were hand-picked from men who had completed their rifle training and they marched to Leamside for the train to Hartlepool, a homecoming in khaki for many of the men who had left the town as civilians just two months earlier.

They were billeted in Hart Road and for a month, the volunteers were set to routine work strengthening the coastal defence trenches and on sentry duty guarding the town’s important docks.

But, across the grey North Sea, a squadron of German ships slipped out of port on the morning of December 15 on a mission to attack England itself, partly to try to turn the country against the war and partly to try to entice the British fleet into pursuit and an open sea battle.

British intelligence had cracked the enemy naval codes and were pre-warned of the mission, but did not want to reveal their hand, so allowed a terrifying bombardment to be unleashed on the unsuspecting towns of Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby.

On the evening of December 15, the War Office notified local commanders to expect a raid the following morning and the Durham Pals found themselves unexpectedly in the frontline of the Great War.

FACING the might of the German navy were two small artillery units, two six-inch guns at the Heugh Battery and one six-inch gun at the Lighthouse Battery, both manned by gunners from the Durham Royal Garrison Artillery and protected by soldiers from 18DLI.

Writing the battalion’s official war history five years later, Lieutenant Colonel William Douglas Lowe, recorded: “There was a mist which allowed the enemy ships to come in close before being detected and they used a clever ruse of firing out to sea as if they were English ships retiring and so misled the coastal batteries for a few moments.

“Most unfortunately, one of the first rounds burst near one of our guards which was being relieved and the battalion suffered its first casualties, losing five killed and eleven wounded, of whom one died shortly after.

“For forty minutes, the furious cannonade continued.”

One of the first shells from Seydlitz landed in the trenches beside the Heugh Battery and killed four of the Durham Pals outright.

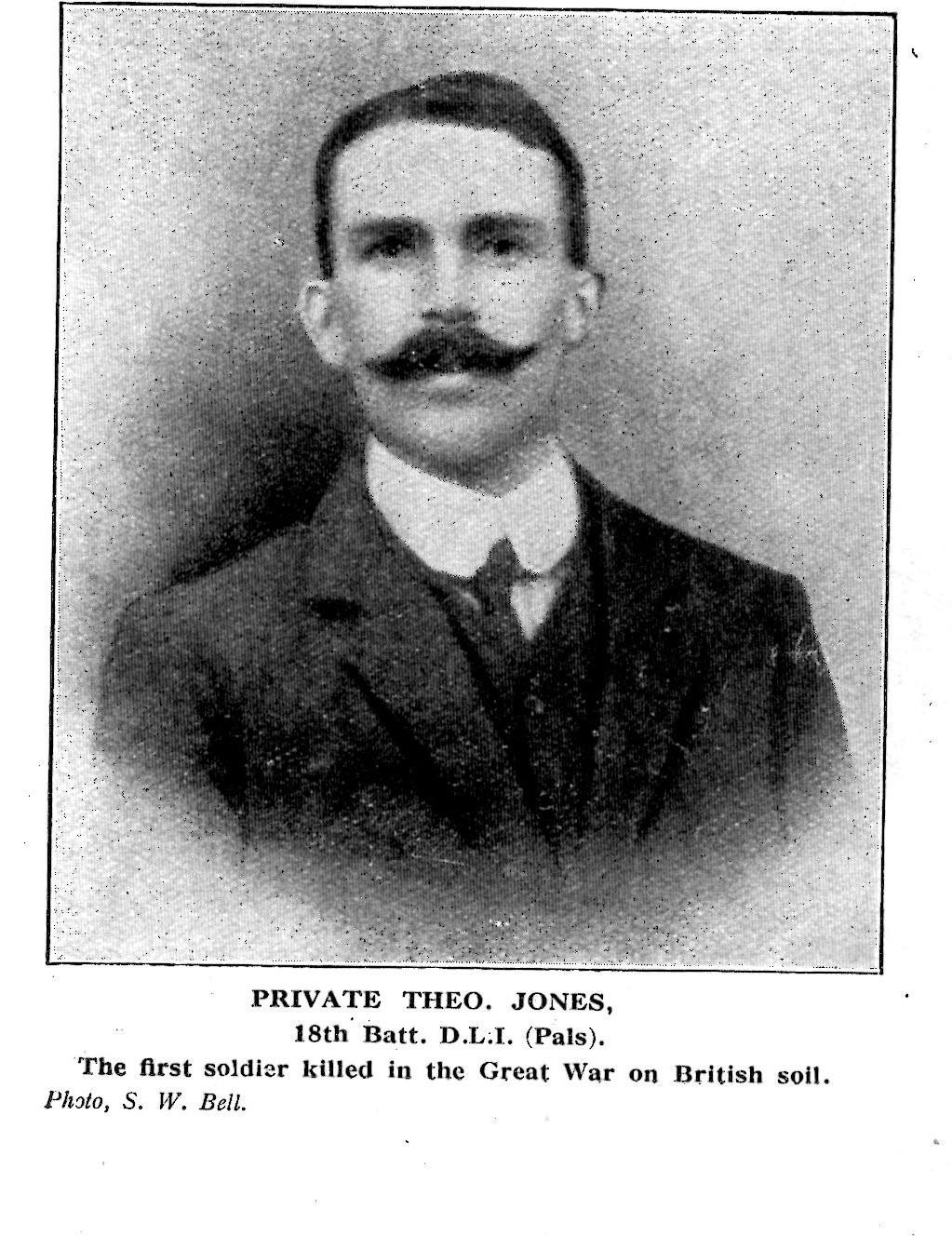

It was claimed that the first was Darlington-born Private Theophilis Jones, a teacher from West Hartlepool, who died defending his home town, although it seems more likely that all four men died simultaneously and Pte Jones was singled out for propaganda purposes.

The 29-year-old had joined the Durham Pals as one of the contingent of old boys from Bede College, the teacher training establishment. At the outbreak of war, he gave up his headteacher’s post in Leicestershire to return home and join the Durham Pals and a prayer book given to him by his schoolchildren was found in his pocket, shrapnel lodged in it.

He died alongside Lance Corporal Alix Liddle, a 25-year-old accountancy clerk born in Carmel Road in Darlington, who worked for colliery firm Pease and Partners. A bellringer at St Cuthbert’s Church in Darlington, he had been married for less than a year.

Also killed in that first salvo were Pte Charles Clark of West Hartlepool and Pte Leslie Turner of Newcastle.

The gunners manning both shore batteries heroically returned ferocious fire and for 40 minutes traded shells with the German ships, landing several direct hits on the Blucher, as enemy fire rained down on their positions and the town.

One round destroyed the Heugh Battery’s radio and the defenders passed orders by megaphone or running amid the falling shells as they tried to help their fallen comrades.

Private Walter Rogers, a 25-year-old, from Bishop Auckland died trying to help those hit in the first salvo. The Northern Despatch reported: “He was killed while in the act of covering up Cpl Liddle. Pte Rogers received the full force of another splinter from a shell in the chest, but he lingered for three hours.”

Another of the wounded, Private Thomas Minks, a schoolteacher and Bede College graduate from Rowlands Gill, died of his injuries two days after the bombardment.

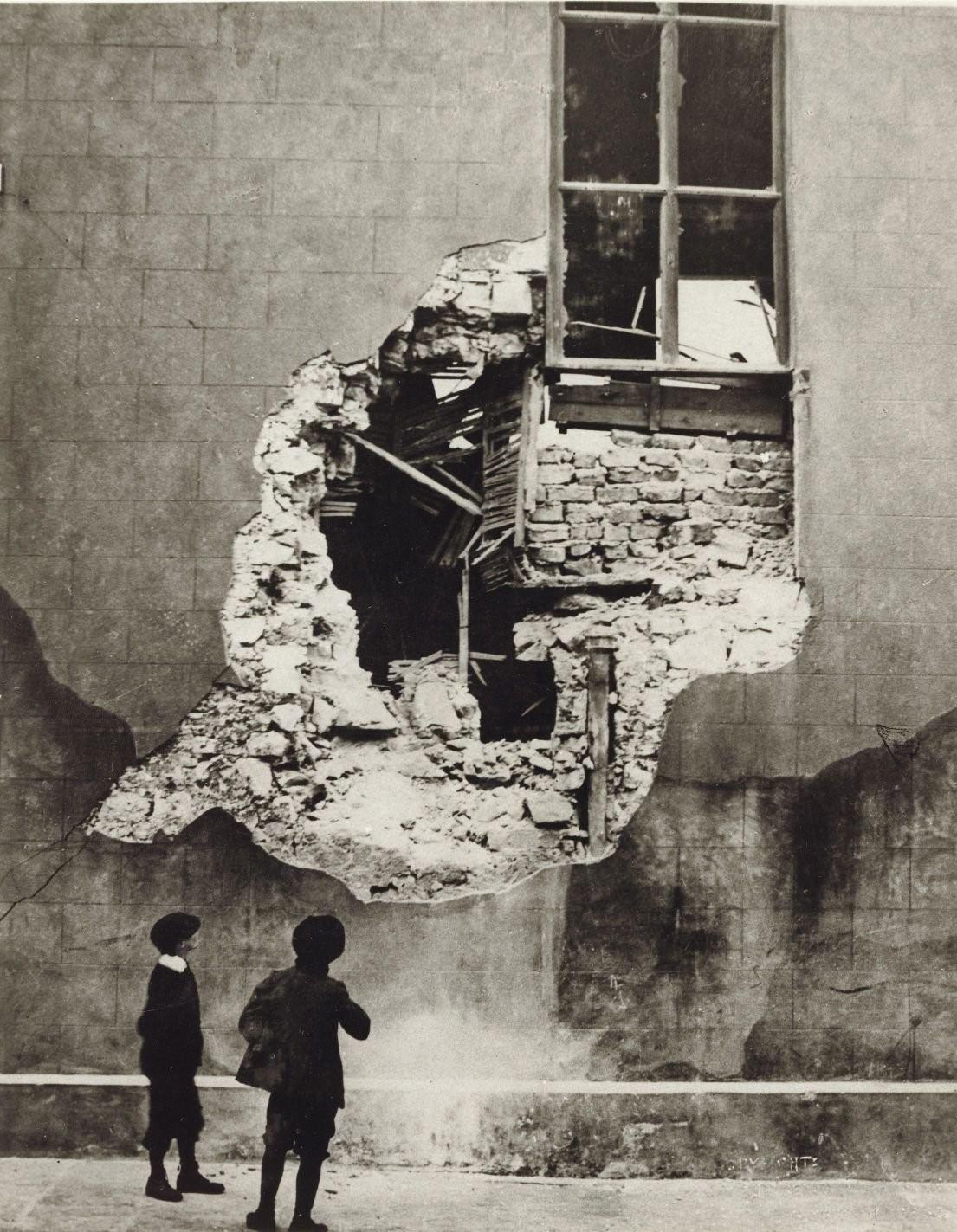

A FURIOUS exchange of fire continued, with the shore batteries landing hits on all three German ships while more than 1,000 enemy shells bombarded the town.

Around 300 houses were hit, with families killed in their own homes, churches were destroyed, children died on the way to school, three of the town’s gasometers went up in flames.

Lieut Col Lowe’s battalion history records: “During the bombardment, some fishermen were bringing in their smack and tried to land on the beach. One of them was left wounded on the beach in the thick of the shelling. Sergeant Heal and Corporal Brewerton at once asked permission to leave the trench and under heavy fire ran down to the shore to the shore and brought him to safety.

“The streets of the old town suffered terribly, the gas works was destroyed and one of the big ship building yards damaged, but the docks and other yards were not touched. Churches, hospitals, workhouses and schools were all struck. Little children going to school and babies in their mothers arms were killed.”

Private Robert Webster, from Hartlepool, witnessed the rescue of the fisherman. He said: “I was ordered into a trench and watched the bombardment of Hartlepool from there. Our trench was hit by a light shell and Corporal Scott was wounded and nearby the gasometer was blazing. Fishing vessels at sea ran for the shore and men jumped into the sea and ran for it. One man hurt or broke his leg and Sergeant Heal and Corporal Brewerton immediately went to his rescue.”

Private John Carr, previously a Weardale tailor, wrote home: “A terrific heavy gunfire was kept up for half an hour.

“A shell burst on an embankment above us, splinters dropped within a few feet of us. Other sections of our battalion have not come through this, our baptism of fire, as well as us. A section on guard at the Lighthouse Battery had a serious misfortune, having five men killed and several wounded.

“Out of 20 men only four escaped unhurt and this was all done with one shell. I am told they behaved courageously and died like true British soldiers.

“The number of civilians killed in considerable. There are many houses in ruins.”

BY the time the German ships sailed away, 86 civilians and seven soldiers, including six from 18DLI, were dead or dying and hundreds of others were wounded.

Amid national outrage, the Durham Pals were left to bury their dead. More than 500 members of the battalion attending the funeral of Pte Jones at St Aidan’s Church in Hartlepool where he was laid to rest with full military honours.

The teachers and clerks of 18DLI had held their nerve under intense enemy fire and had not been found wanting.

General Plumer, senior officer with Northern Command, reported to Lord Kitchener: “If the enemy had followed up the bombardment by attempting to set foot on our shores, the behaviour of the troops was such as to assure everyone that they were fully prepared and would have been able to render an excellent account of themselves.”

With typical understatement, Lieut Col Lowe recorded in the battalion history: “The behaviour of the battalion was equally satisfactory, they had been the first service battalion to come under fire and the men all displayed coolness and gallantry under heavy fire.”

• Next week: Submarines and sandstorms – the Durham Pals’ desert adventure

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here