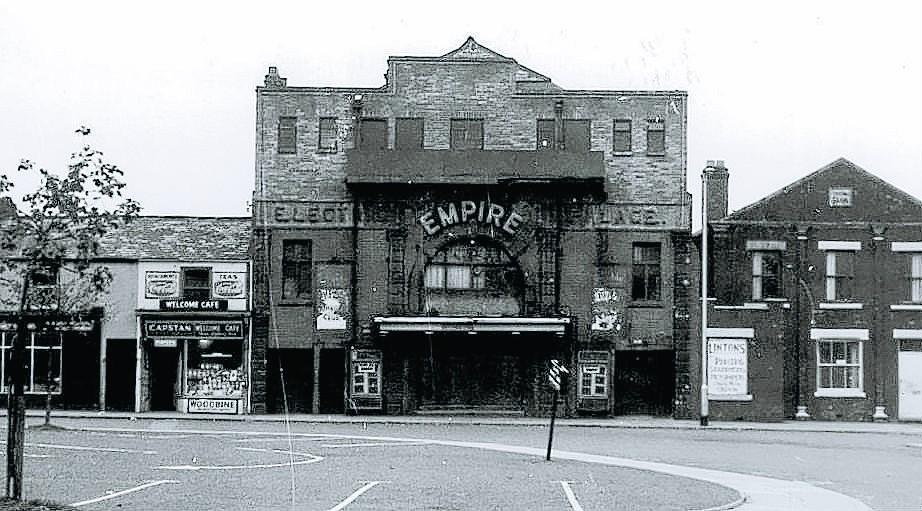

A determined band of enthusiasts are busy setting the stage for Britain's fourth oldest cinema - now a car parts store - to be brought back to life

AT the front of the building, Speedo Car Parts is busy selling everything from sparkplugs to turtle wax, from air filters to clutches, shock absorbers to suspensions…

Occasionally, a blue-overalled salesman opens a door behind the counter and darts off to get a bottle of lubricant.

As he goes, the open door reveals a tantalising glimpse of the other world that lies behind the car parts counter. There’s a hint of grandeur from gold paint on what appears to be a huge piece of arched decorative plasterwork, and there’s a feeling of faded opulence in the peeling mauve flock wallpaper.

And there are decades of dust.

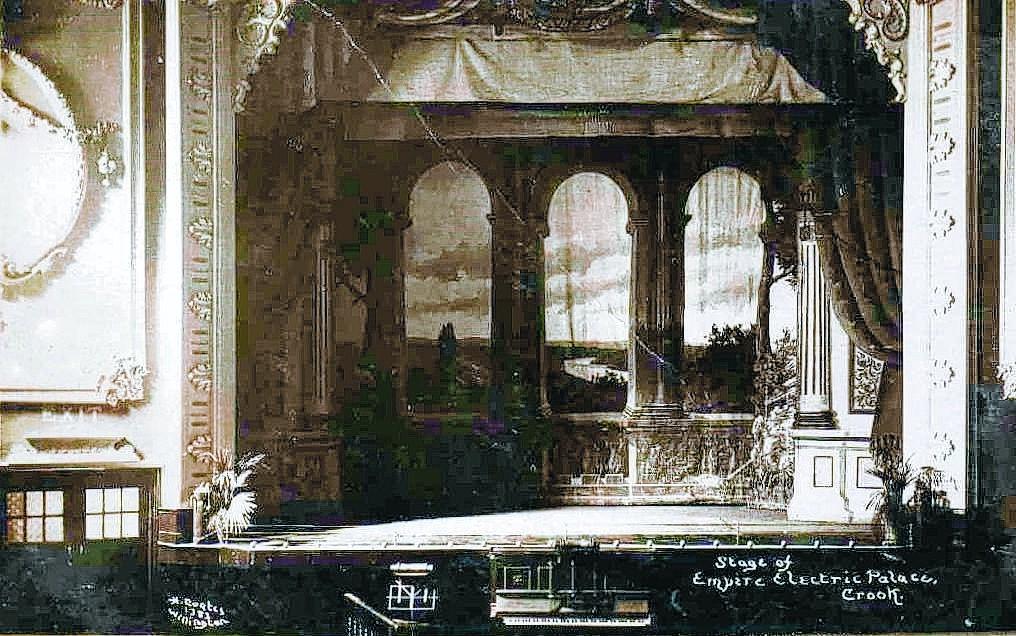

ON THE STAGE: Much of the mouldings around the Empire's arch remain from this early postcard. Note the organ in the centre of the picture for accompanying the silent movies

These are the remains of the oldest surviving purpose-built cinema in the North-East, which are practically untouched since it closed in the late 1960s.

Now a group of volunteers wants to bring the Empire Electric Palace in Crook – the fourth oldest surviving cinema in the country – back to life, and is appealing for help from anyone with time, skills, money or memories.

The Empire – or “Bottom House” – opened on Monday, November 14, 1910, overlooking Crook Market Place, “in the presence of a crowded attendance”.

The Northern Echo said: “Mr Lowther JP, in a neat speech, declared the palace open, and said he hoped there would always be exhibited pictures which would be entertaining and elevating.

“It was a splendid house of entertainment for Crook.

“The National Anthem was sung by the audience. The pictures were of the highest order, and gave immense satisfaction.”

The first films were shown in London by the Lumiere brothers in February 1896. Their popularity rapidly spread, first through travelling fairgrounds, and then through hasty conversions of music halls and shops, which, with their windows blacked out and a rear wall painted white to act as a screen, became “penny gaffs”.

But those first, flickering pictures were on cellulose nitrate film, which had a worrying habit of bursting into flame.

In 1909, the Cinematograph Act was passed, requiring all film projectors to be enclosed within a fire resistant room, and all buildings showing films to be inspected by the local council to make sure audiences could be evacuated safely in the event of a fire.

Many of the crudely converted penny gaffs failed the most basic test. Suddenly, the race was on to build proper, safer, cinemas.

Quite how Crook came to be at the head of the race is difficult to say. The Electric Empire Palace seems to have been a speculative venture based in North Shields – architect Pascal Stienlet was from there, as was the builder and first owner, WS Shepherd.

Much of what they created still survives, even though the downstairs chairs – including the lovers’ favourite doubleseats – have been ripped out to create room for the Speedco Car Parts shop.

But above the shop – up a knee-creakingly steep staircase – is the balcony, with several hundred red, plush, flip-up seats, filled with scrunchy, scratchy, horsehair, still waiting for an audience.

At the back of the balcony is the projection box, its ceiling asbestos and its floor an enormous dollop of concrete. Fire would have struggled to break out of here – and if it did, on opening night the Empire boasted that its auditorium could be evacuated in just three minutes.

The projectors threw the films over the heads of the people in the flip-up seats and down towards the proscenium arch and the screen.

Today, the proscenium arch looks like it has been cut off at the knees, but that’s because a false ceiling has been put horizontally across it, so that the car parts company has storage space behind its front counter.

Covered in dust, the gold arch still looks splendid, with its fanfare of acanthus leaves on the sides and a grand shield in the centre.

The arch is flanked by large oval plaster mouldings, like grand picture frames, with ornamental vines tumbling from them. In the 1920s, gold-and-purple wallpaper with a leaf pattern was pasted into the picture frames to give them an air of extravagant elegance.

The ceiling, though, is bare. Its black paint is peeling off in streaks that hang down, and on a side wall, where the plaster has fallen off, there is a bricked-up window – a reminder that when 700 or 900 people crammed in during the early days, mingling their body odours and puffing out cigarette smoke, ventilation was desperately needed.

But it would be magnificent to get an audience back in the historic cinema – and a group of volunteers has been formed to Save the Empire. They are already registered as a charity, and are beginning to apply for grants to turn the Empire into a community facility, showing films, putting on performances, holding exhibitions, training young people…

“We want people to become aware of what we have here,” says Aaron Cowen, the group’s founder. “A lot of our potential funding is reliant upon us showing we have got lots of people supporting us. We need people to get involved, to distribute leaflets, to sell ice creams, to give us their memories.

“We need their enthusiasm.”

You can email the Save the Empire group at info@eep-crook.org or call 01388-240024, visit their website eep-crook.org or like them on Facebook: facebook.com/Save-the-Empire

THE Empire Electric Palace was designed by architects Pascal Stienlet and Henry Gibson. Mr Gibson first worked in Crook in 1897 when he designed the belltower on the Our Lady Immaculate and St Cuthbert Roman Catholic Church.

Mr Stienlet was of Belgian descent, the son of a South Shields’ ships chandler. The palace was his first cinema, and over the course of his career, he may have designed as many as 200 of them. The most extravagant was completed in 1922: The Majestic at Leeds. It held 2,500 filmgoers, was richly decorated with a grand Sunderland-built organ, and had a ballroom in its basement.

But The Majestic was badly damaged by fire on September 3, 2014.

Mr Stienlet’s grandson, Vincente, 75, still runs the architects’ practice on Tyneside, and visited the Electric Empire Palace for the first time last week. “It’s nice and cosy and has great potential,” he said. “It has a great sense of its time.”

ON November 19, 1910, at the end of the Empire’s first week of operation, The Northern Echo said: “An excellent programme will be submitted at the new Empire Picture Palace at Crook next week. Amongst the many pictures which will be shown will be: A Rural Romeo, The Broken Symphony, Cowboy Chivalry, Sorrows of the Unfaithful, Glimpses of Bird Life, A Tour Through Indo-China, and a host of comic subjects. The Bijou Orchestra will render selections each night.”

Long feature films weren’t made until 1914, so this programme of silent shorts was entirely typical. The first four titles appear to be romantic America films, all made in 1910.

In A Rural Romeo, for example, a wealthy city girl crashed her automobile around a country tree and a big, muscular yokel carried her to his shack for treatment – can their love from such different backgrounds thrive?

Sorrows of the Unfaithful concerned two childhood sweethearts, Bill and Mary, growing up by the ocean from which, one day, Bill bravely rescues a stranger drifting on raft. Mary falls in love with the stranger, Joe, who clearly has affections for her, but rather than break the heart of man who saved his life, he re-boards his raft and prepares to let the currents seal his fate.

Just as he’s casting off, Bill arrives, furious that Joe has tried to steal his girl. He punches Joe in the face and pushes him out to sea.

Then Mary explains the honour behind Joe’s sudden departure and Bill, heartbroken by his violence, wades out into the breakers in a futile bid to find his drowned friend, leaving Mary standing all alone on the beach in tears…

Can you imagine the swirling, swelling music that the Crook Bijou Orchestra must have played to accompany such a melodrama?

THE Empire – or “Bottom House” – was the first of Crook’s three cinemas.

The “Middle House” was the Royal Theatre in Addison Street, which was opposite the Coach and Horses pub. The Royal Theatre is believed to have been run by Wallace Davidson whose grandson, Richard Greene, became a devastatingly handsome Hollywood actor and starred in the 1950s TV series, The Adventures of Robin Hood. He also appeared on Morecombe and Wise, Dixon of Dock Green and The Professionals.

The site of the “Middle House” is now a little car park.

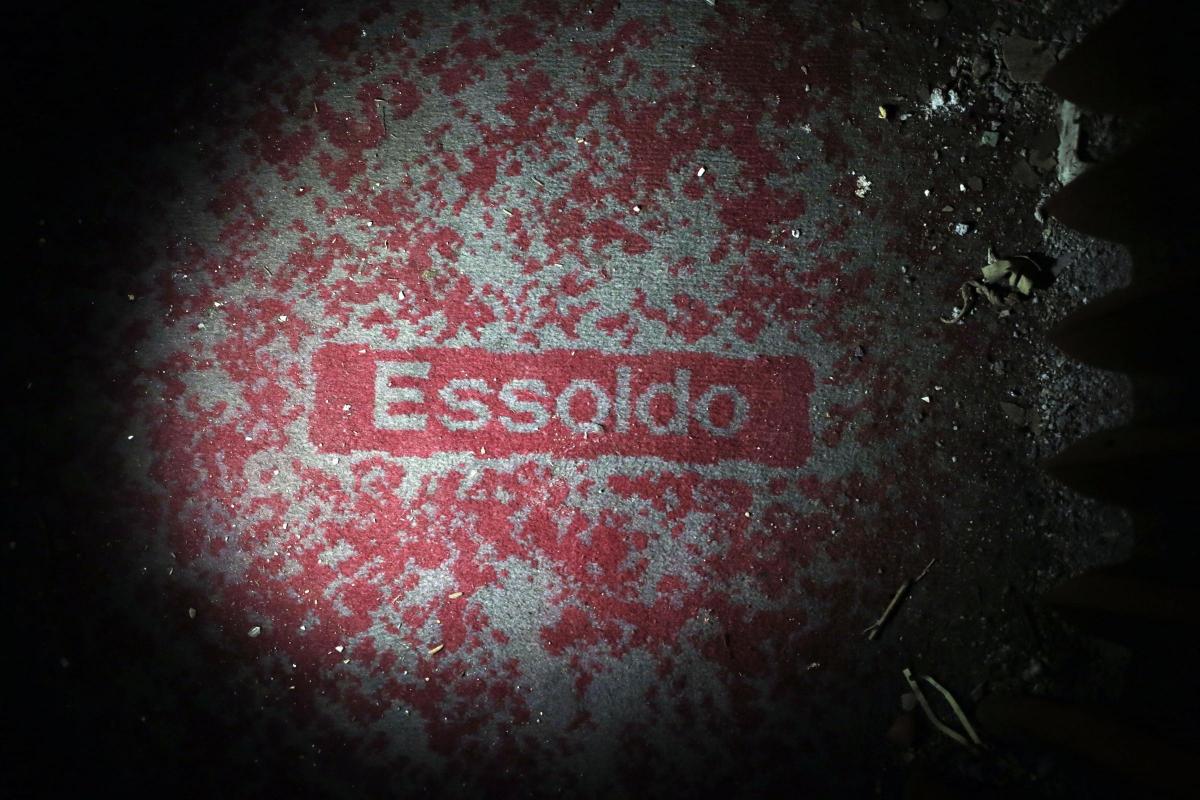

The third cinema was the Hippodrome – the “Top House”. It was built in the 1920s on the road out to Billy Row, was later known as the Essoldo and was demolished in the early 1970s so that Royal Grove could be built on its site.

So the Empire outlasted the other two. In 1949 it, too, became part of the Essoldo chain and an extremely grubby red and gold Essoldo carpet still lines the balcony.

In the 1960s, as the age of the cinema was overtaken by the era of the TV, the Empire became a bingo hall. It closed in 1968 and was empty for two decades until the car parts company moved in.

Hopefully in 2016, the Empire Electric Palace can be returned to something approaching its original glory.

DO you have memories of any of Crook’s cinemas? Please contact Memories: chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk or 01325-505062.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here