Educated at the illustrious St Martins college, Mark Rowney has produced work for everyone from Vogue to Prince Edward. Now the Weardale artist is focusing on his intricate leathercraft, which he says is the pinnacle of his career. He talks to Sarah Millington

MUCH of Mark Rowney’s life has been dictated by luck and boredom, and it is to both that he attributes his latest specialism of leatherwork. Living in New York, having exhausted life as an illustrator for leading London publishers, he was replicating his success on titles like the New York Times and Time magazine. Then he made a discovery in the basement of his apartment, and the course of his life changed irrevocably.

“I found a box of leather and tools and I recognised it because my father did a bit of leatherwork,” explains Mark, who speaks in a warm Yorkshire accent. “I just started making things and then about six months after I found all this stuff, I had a bag full of things that I’d made and I thought, ‘I wonder if any shop would be interested in selling them’. I pounded the streets down Fifth Avenue with this shopping bag full of leather things and I saw this Paul Smith shop and I went in and saw the manager and ended up pretty much supplying goods for Paul Smith for about three years.”

If all this sounds too good to be true, then the same can be said for a lot of Mark’s life. The son of Country and Western-obsessed parents who created a ranch at their Weardale home, Mark grew up with the dual influences of cowboys and the countryside. Always artistic, he studied at London’s Central Saint Martins art school, famous for churning out celebrities, and dreamt of becoming a wildlife illustrator. His heroes were the those whose drawings graced the pages of the Radio Times – and, fresh out of college, he found himself among them.

“On the very last day of my degree show I went and looked in my book and the very last comment was left by the art director at the Radio Times,” says Mark. “I couldn’t believe it. It was like, ‘Where do I go from here?’”

He came to the answer of New York via a stint working for Penguin – but after several years as an illustrator, the job was beginning to wear thin. Despite his success, Mark was bored – or at least, creatively unfulfilled – and it was this that prompted him to take up leatherwork. Paul Smith provided the perfect showcase and, at one point, Mark’s two careers converged when Vogue featured his artwork and models wearing his leatherwork in the same edition. His presence at the designer store also led to a job offer.

“There were two ladies who were buying my work who approached the manager to speak to me and asked me if I would be interested in becoming their designer,” says Mark. “They were starting up a soft furnishing company. I jumped at the chance. It was mainly embroidery work, which I’d never done, and they said, ‘Would you be interested in moving to India to help start up the factory?’”

Over the next three years, Mark found himself making regular trips to India, spending six or seven months there at a time establishing the new company. He describes the experience as “sort of beautiful and horrible”. “It was exciting, but very hard work and very tough conditions,” he explains. “By the end of it, I was burnt out, so I decided I was going to return to the family home in Weardale and pursue my own love of painting. I kind of realised that I went to art college to become an illustrator. I always had a passion for nature. When you’re working in the commercial world, you don’t really have a chance to do that.”

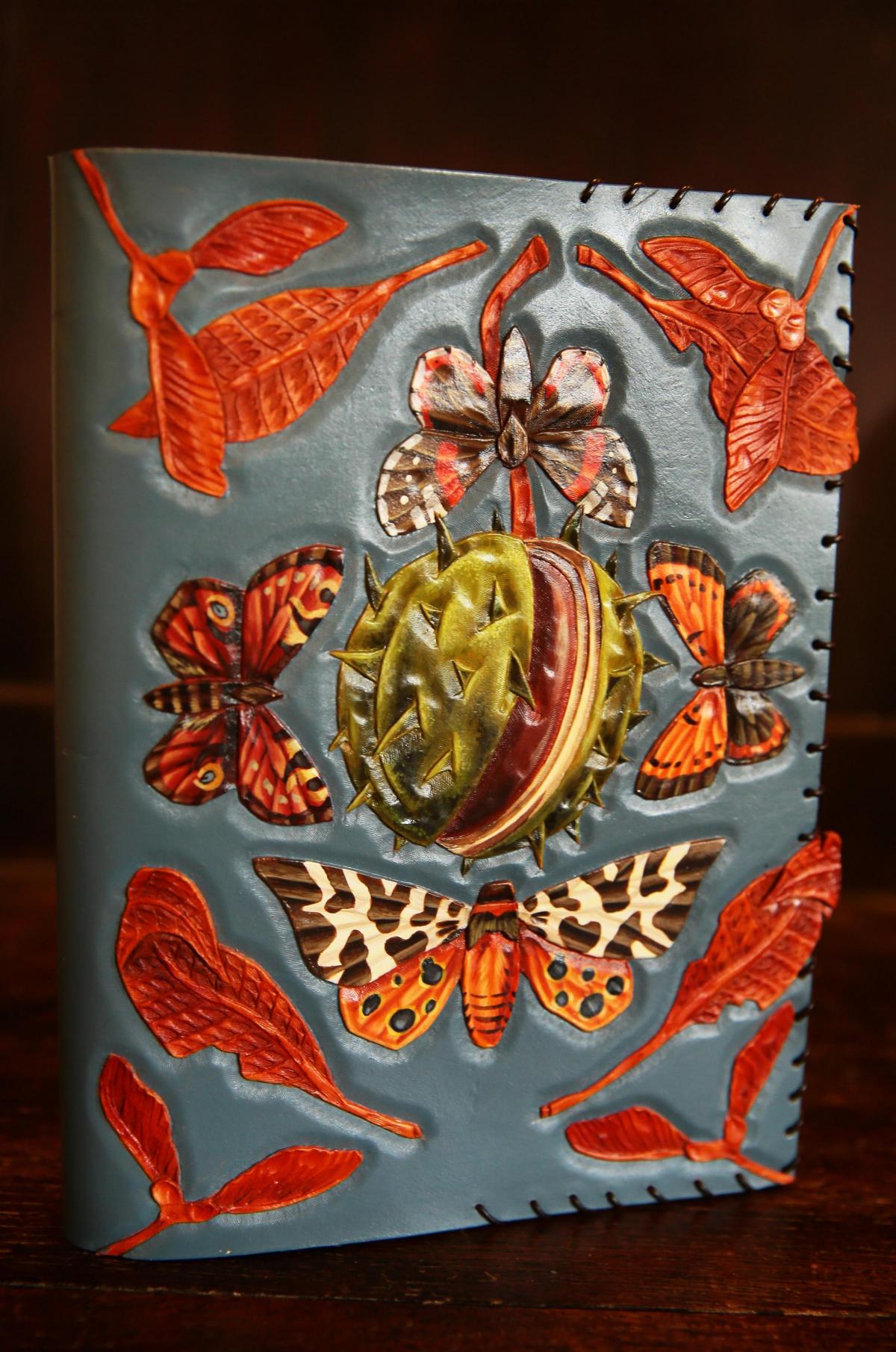

For a while, Mark combined painting with leatherwork, using the countryside around him as inspiration. Intricately carved, and with breath-taking detail, his leatherworks to date have been mainly decorative art on things like book covers. A career highlight was being asked to produce a journal for Prince Edward to mark the opening of the Forge Studios and Art Gallery in Allendale. “It took me six weeks and it was absolutely beautiful,” says Mark. “You’re waiting for the phone to ring to get work from lots of important people, but it never seems to happen that way. Thank God for the internet. It opens up your work to people you would never meet.”

While admitting that he’s no millionaire, Mark is successful enough that, with a supplementary income from his wife Mary, he can follow his own artistic path and doesn’t have to bow to commercialism. To him, this is crucial – and as his leatherwork has developed, he has decided to concentrate exclusively on it. A true craftsman, he loves its tradition and its discipline.

“I just do sculptural leatherwork now – probably the most interesting work I’ve ever done,” says Mark. “I kind of feel top of my game. It’s a very, very old craft. It’s very popular in America – I would say 80 per cent of my commissions are from America – but actually, it’s a very ancient English craft as well. There are not many exponents of it and I always just saw there was a gap in terms of what was being produced, and that was the more artistic way of working.”

Mark is currently working on a new collection, exclusively previewed here, which he plans to show early next year. Describing it as “a brand new departure, typical of me”, he explains that it’s made up of leather sculptures, larger than his previous work, to serve as art for interiors. “For instance, I’m doing doors with leather panels now,” he says. “Each of the panels tells a story. I’m doing pieces with a situ in mind – there are little love letters to people that they can hang above their beds. It’s the culmination of 30 years of leather carving.”

Often spending 18 hours at a time in his workshop and working seven days a week, to Mark, his art is his life – he simply couldn’t exist without it. He describes his inspiration as “the bees that sting me, the midges that bite me and the birds that sing so sweetly”, yet isn’t content simply to represent the wildlife around him, preferring to explain and interpret it. “When you observe nature, even the lowliest bugs and the greatest birds have their own stories and idiosyncrasies,” he says.

Another prevailing impulse is to see things afresh, as if through a child’s eyes. “Last year I had to go and teach in schools and when it came to an end, I was almost in tears, I loved it so much,” says Mark. “I loved the way they saw the world. They had so much freedom of expression. It seems to me that there is an age where children are able to react in a very personal way to all sorts of stimuli. I’m trying to draw that out of myself, without, I hope, producing childish work.”

Ultimately, Mark considers himself profoundly fortunate. “It’s never been about making a living for me,” he says. “I’m now 54 and I’m still here doing what I want to do. If I have another 15 or 20 years doing what I want to do, then I will have succeeded.”

- www.rowneyart.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here