The previously untold stories of women in mining communities across the region are being brought to the surface in an exhibition which opens in Bishop Auckland today. Jenny Needham reports

HANNAH was born at Great Lumley and at the time this image was taken she was living in tied agricultural workers accommodation in Paradise Row, Shadforth, working on the farm in lieu of rent. At the end of her life she opened and ran a hardware shop in the front room of her private-rented accommodation at Ludworth.

I believe her husband, John, would be sending money to her via the local Post Office in Shadforth. As both were unable to read and write, they would both be dependent upon the literacy skills of Post Office staff.

John was away for eight years and he returned to County Durham in about 1864, finding employment at Ludworth Colliery. Like most miners in the 19th Century Durham coalfield, he was unhappy with his working conditions and the treatment miners received at the hands of the private coal owners. This lack of recognition for the difficult and dangerous jobs they did was responsible for miners becoming unsettled. When coal mines opened in Australia and America, some men, John included, felt they had nothing to lose by taking up the offer of a new life in a new world. John went to Australia to assess whether his family could settle there.

The picture of Hannah is the earliest example of naturally developing colour on a glass plate that Beamish Museum had ever seen. As photography was in its infancy, I am surprised at how Hannah, an illiterate woman from an isolated farming community, would even know about the new invention. The gold on the photograph is actual jewellery and indicates that she was able to make a decent living for herself and the children whilst John was away.

– Wheatley Hill family history researcher Margaret Hedley, Hannah Porter’s great great granddaughter

THE image is striking. A mother and her two daughters in a photographic studio in 1862, precious gold adorning fingers, necks and belt buckles. The dresses and jewellery might give the impression that the family enjoyed some wealth and a life of relative ease.

Their faces, though, belie this tale; they speak of tough times. The woman is Hannah Porter, from County Durham, who established and ran a hardware shop from her home, took in lodgers, worked as a dressmaker and did all manner of jobs to earn a wage after her husband left for the newly-sunk mines of the United States.

Commissioned at great cost at the very advent of photography, the hand-coloured image was sent to her husband overseas, perhaps as a message that the family were thriving in spite of his absence. What the picture really illustrates is Hannah's resilience and ambition in the face of hardship. And the fact that she was obviously a shrewd and skilful financial manager.

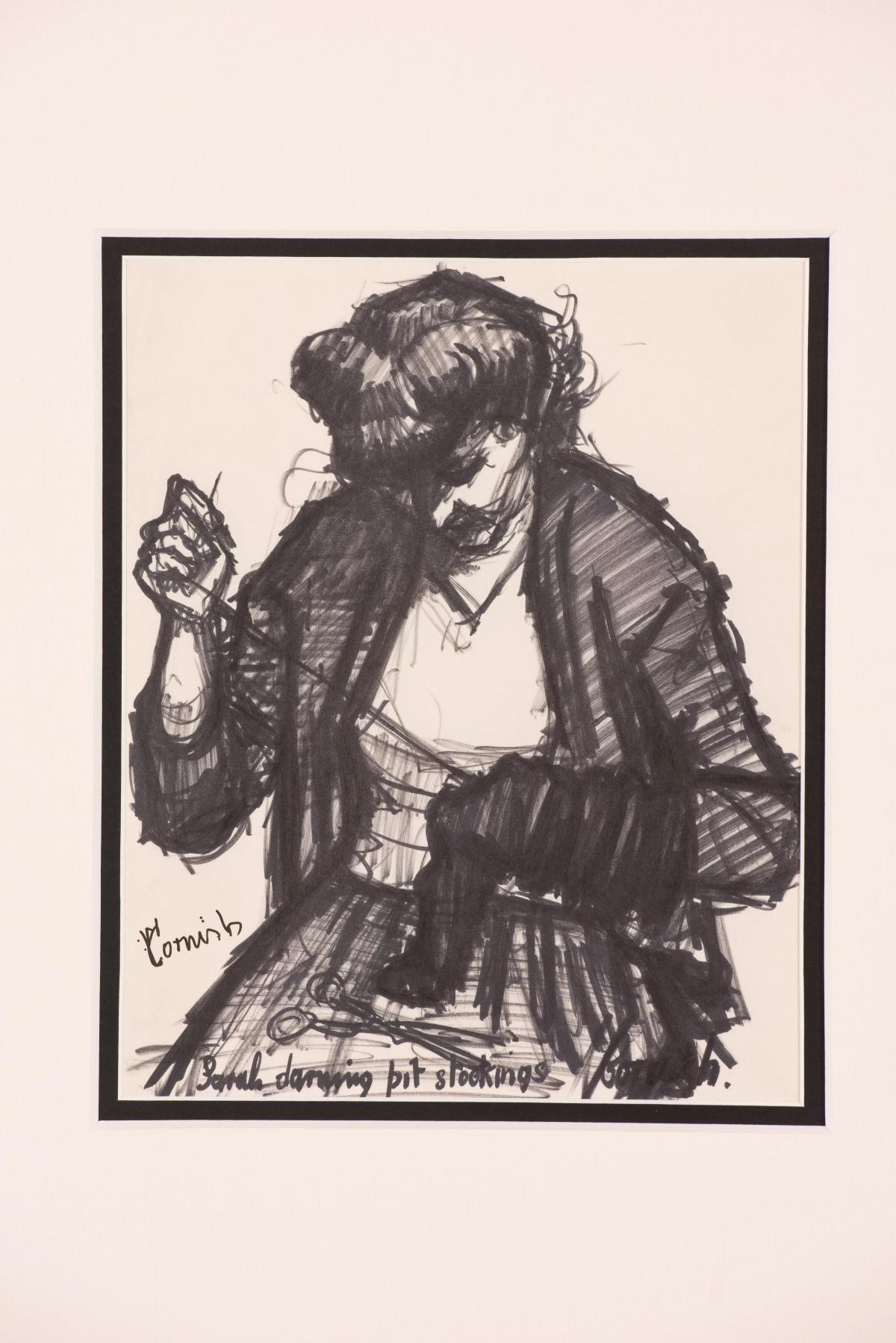

Hannah's tale, and previously untold stories of women in mining communities across Durham and Northumberland in the 1800s are being brought to the surface in a new exhibition, Breaking Ground: Women of the Northern Coalfields, which opens at the Mining Art Gallery, in Bishop Auckland, this weekend. The temporary exhibition showcases the role women played in the regional coal mining communities of the 1800s. Artworks, archive images and personal histories all highlight the tenacious spirit of these women, whether working at the colliery as "pit brow lasses" or taking on multiple jobs to keep a roof over their families’ heads.

The "pit brow lasses" – also known as "tip girls" or "pit bank women" – earned a wage doing hard physical work hauling tubs or picking stone from coal. Wearing rough trousers and heavy boots instead of demure dresses, these women shocked Victorian society, but in spite of multiple attempts to force them from the pit heads, they continued until the last one retired in 1976.

At one time, there were between four and five thousand pit brow women, which represented only a fraction of the total colliery workforce and less than seven per cent of surface workers, so the stir they caused was out of all proportion to their numbers. But the investigation which brought about the Mines and Collieries Act temporarily shone a light on this self-contained working community that outsiders found difficult to comprehend. "For them, the work that the women were doing was indistinguishable from the work that the men were doing and in the most masculine of domains," says Angela Thomas, curator of Mining Art at The Auckland Project. "It was as far removed from the Victorian drawing room as society could imagine."

Other women in mining communities inhabited more traditional roles, often holding down a number of jobs to feed the bairns and keep the bailiffs from the door.

They were, almost without exception, talented seamstresses. This was a skill they were trained in from a very young age and as well as making/mending their own family’s clothing, they would take in mending to make extra money.

Due to the richness of the huge amount of mines being sunk in the area during the 19th century, there was an huge influx of able-bodied men from other areas of the country such as Wales and Cornwall. Populations of towns and villages doubled and sometimes tripled with single men who had moved for work – women took in these men as lodgers, which significantly increased the family income, but also increased the cooking/cleaning/washing workload. "Other miners' wives took on agricultural work, particularly around harvest time," says Angela. "We also have reports of women opening shops from their homes and outbuildings to supplement the family income."

Local stories like that of Hannah Porter's feature in the exhibition alongside works by artists such as North-East artists Tom McGuinness and David Venables. Venables' own mining heritage can be traced back at least as far as the 19th century and as a young artist he felt compelled to rediscover his roots. He knew his family had originated in Lancashire but had moved to the North-East to follow work as miners. In the 1960s, when visiting relatives in Wigan, David found himself at one of the local collieries. Fascinated by the machinery, buildings and the people, he began to make a series of sketches, some featuring women hard at work on the conveyors and screens, sorting and processing the coal brought up from the pit bottom. It was only three years ago that he finally brought together the sketches he had made over 50 years ago to produce the painting entitled Pit Brow Lasses.

Earlier in the 18th century, women worked underground, though they appear to have stopped going down the pits in the North-East around the 1780s – well before the Mines and Collieries Act forced women to the surface in other areas. "This could be due to the large amount of men that moved to the region to work in the pits, meaning there were fewer vacancies for women to fill," says Angela. "Additionally, the North-East had a high standard of safety and fewer accidents compared to other regions of the UK, which meant there were fewer widows or women who had to support injured miners."

In fact, most experiments to make mines safer were concentrated in the North-East and the South Shields Committee set up in 1835 to investigate safety openly condemned female pit labour. "There are few records that mention women even working at the surface of the collieries of the North-East, probably because they just didn’t need to," says Angela.

Nevertheless, life was terribly tough for pit village women, an endless round of hard work, hunger and grinding poverty. "With 2018 marking 100 years since some women in the UK were granted the right to vote, this is the perfect time to shine a light on the significant, but often overlooked, role of women in the northern coalfields," says Angela. "Their strength and fortitude was constantly put to the test, whether they were fighting to keep their jobs or determinedly keeping the home fires burning.”

n Breaking Ground – Women of The Northern Coalfields, Mining Art Gallery, Bishop Auckland, until Sunday, March 24

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here