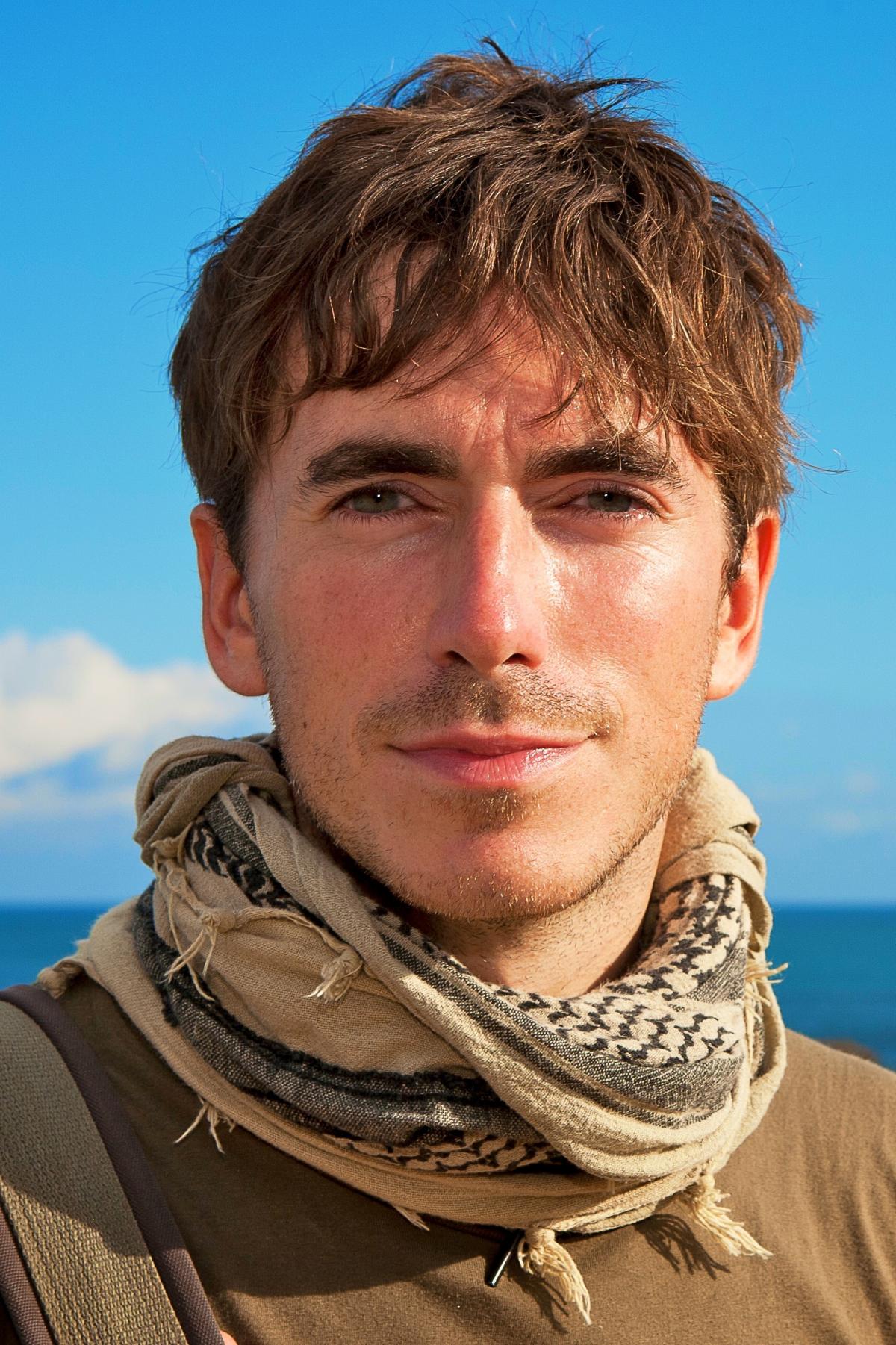

SIMON Reeve has been to some of the most dangerous places in the world. His live show aims to inspire people to follow in his footsteps, he tells James Rampton

What inspired you to do this new live show?

I’ve had some magnificent adventures and met some of the most inspiring people on the planet. So obviously I’ve got lots of tales from my travels, and this show is a tremendous opportunity to share them. There’s a lot that I see and film that never makes it into the programmes, so there’s also behind-the-scenes stories to tell and footage to show.

I’m very keen that people push themselves into unfamiliar territory. The world can seem a scary place, but it really isn’t. This is the golden age for travel. These days, ordinary people can have adventures that in the past only kings and queens could have dreamt of. You can go anywhere now. But people are sometimes reluctant to leave their holiday resort. They are told that they should simply go to a resort and sit by the swimming pool being milked for cash while being served drinks in primary colours. I’m urging people to go beyond the confines of the resort. That’s where you get the best memories.

Will you have some pre-show nerves?

Yes. Imminent death doesn’t bother us as much a social embarrassment!

Do you hope this show might inspire people?

I hope it might prompt them to go on their own adventures and encourage them to get out of their comfort zone in life. I also want to remind people that starting from nothing doesn’t need to stop you from achieving your dreams. Everyone seems to think that to be on TV you need to have got straight As at public school, but I don’t come from a media family or a wealthy, travelling background, and I left my local comprehensive with basically nothing and went on the dole. I started work in a mailroom. I never went to university.

Was adventure part of your upbringing?

No. I definitely wasn’t born into it. When I was a kid, we only went abroad once when we took the ferry to France to go camping. I didn’t get on a plane till I was working. When I was growing up, people didn’t travel in the way they do now. People have forgotten that. I remember the first Spanish and Greek restaurants opening in London during the late 1970s. That was the result of British people taking Freddie Laker-type flights abroad. I only came to travel and adventure as an adult.

What was your childhood like, then?

I grew up in tropical Acton in West London. My adventures were restricted to riding my BMX and my grandmother’s magical mystery tours. She would take my brother and me in her car when we were very little to explore exotic, unknown places like Hounslow. Sometimes we even got as far as Chiswick!

How were your school days?

I didn’t get on with school. I flunked an exam, walked out and never went back. I was on the dole for a long while. Then I got a few jobs before becoming a post boy on the Sunday Times, and my world began to open up. Editor Andrew Neil was keen to give the post boys an opportunity to have a crack at working on the paper. Everyone else on the paper was Oxbridge, but I was keen and eager and they gave me a chance.

How did your career progress from there?

I was this pathetic kid suddenly thrown into an environment where people were doing very exciting things and working on serious investigations. I carved out my own niche. First I became an expert in fixing these vital big photocopying machines they had, so they couldn’t sack me. Then I fell into investigating terrorism, as you do. I started researching the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993, and eventually wrote the first book on al Qaeda, which came out in 1998. Nobody read it. Then I wrote some other books and worked on hardcore investigations where I spent time undercover.

What changed things for you?

9/11 happened, and suddenly I was chucked into the world of TV. I’d written the only book in the world about the biggest story of the time. I also knew people who died as the Towers came down - I’d met them when I was researching my first book.

The BBC wanted me to make a series for them. The first ideas were a bit daft. They included wanting me to infiltrate Al Qaeda. I didn’t think that was a very good idea. In the end we settled on the idea of going on adventures in parts of the world that weren’t often on the TV. The first BBC series I did in 2003 was called Holidays in the Danger Zone: Meet the Stans, and it was all about my journeys in the Stan countries to the north of Afghanistan, including Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. I loved it from the first day of filming. Since then I’ve made more than 100 programmes around the world.

What can you tell us about the BBC TV series on the Mediterranean that you are currently filming?

Well it’s an extraordinary part of the planet. Nowadays we can go anywhere in the world, but sometimes we overlook what’s closest to home. I’m just blown away by how extreme life around the Mediterranean can be. We forget there are magical and horrific places close to our own doorstep.

Is there anywhere you wouldn’t travel?

I don’t think so. It really is a very safe world, as long as you take some basic precautions. You can travel almost anywhere, as long as you wear a seatbelt and avoid hotel salad buffets!

What are the most unusual things you have eaten on your travels?

I’ve eaten everything from penis soup in Madagascar to barbecued rat in Laos. That was so bad that even the scrawny dogs in the local market wouldn’t touch it. I’ve even had a roasted sheep’s eyeball, which was actually rather delicious.

On your travels, you have done some extraordinary things, such as being arrested for spying by the KGB, electrocuted in a war-zone, protected by stoned Somali mercenaries and witnessed trench warfare in the Caucasus. But what has been your most extraordinary experience?

It’s hard to pick just one. But In the city of San Pedro Sula in Honduras – the deadliest place in the world outside an active war zone – two colleagues and I went into a prison controlled by the inmates. It had thousands of men crammed into a very tiny space. It housed some of the most dangerous people on earth, people who have skinned other gang members alive. It was a cross between Diagon Alley in Harry Potter and an 18th-century sweatshop. It had all sorts of shops like a barber’s and a café, and people were making candles, clothes and wigs in their little cell factories.

We thought of going in with special forces as our guards, but they would have been ripped apart, and the inmates would then have turned on us. So we went in with the very best bodyguard anyone could have in that situation: the Bishop of San Pedro Sula, wearing a very large crucifix. He could look after us and stop the ludicrously dangerous gangs from holding us hostage or chopping off our heads.

Do you let your young son come face-to-face with danger?

I’m really keen on people doing more and going further and pushing themselves. But that doesn’t entirely apply to my seven7-year-old son who I intend to tether to my ankle till he’s in his 30s! Having said that, we’re fairly relaxed about most dangers. We live in a wild and remote spot, and every day my son runs through the forest with our big dog. He’s got an enormous playground to enjoy right there.

What does your wife Anya (camerawoman and campaigner.) think of your trips?

For some reason she’s just keen I up my life insurance above the rate of inflation. No, she’s very adventurous herself, and she knows that adventures add huge meaning to life.

Do you think you’ll ever get bored of travelling?

Absolutely not! What telly presenter would say, “I think I’ve seen enough now”? As long as I’m allowed, I’ll be out there. When I’m travelling, my senses are not just tingled but rattled every minute of every hour.

- Tickets for An Audience with Simon Reeve are available at www.simonreeve.co.uk

- Billingham Forum ,October 8. T: 01642 552 663; W: forumtheatrebillingham.co.uk

- Sage Gateshead, October 9. T: 0191 443 4661; W: sagegateshead.com

- Harrogate Royal Hall, October 23. T: 01423 500 500; W: harrogateconventioncentre.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here