VERONICA BIRD joined the Police Service on May 6, 1966, the day that Myra Hindley was imprisoned for life. Years later, in November 2002, the month that Hindley died, she retired and now lives in Harrogate. The intervening decades she spent working her way up the career ladder, becoming a well-respected prison governor and being awarded an OBE.

“It is an irony, is it not, that completely innocent people with no criminal record whatsoever allow themselves to be held behind bars in grim prisons each day, where they can smell, and feel the experience of the inmates doing their stretch,” it says in the foreword to her biography, Veronica’s Bird.

An innocent abroad when she first joined the service – as a young WPC, Veronica had no idea what a condom was when a prostitute emptied some out of her bag – her determination and ambition overrode all the obstacles she found in her way.

These included a tough upbringing. Veronica was one of nine children living in a tiny house in Barnsley with a brutal coal miner for a father. Life was a despairing time in the Fifties as Veronica sought desperately to keep away from his cruelty.

Astonishingly to her and her mother, she won a scholarship to Ackworth Boarding School where she began to shine among her classmates, becoming a champion in all sports. At last, she’d found some happiness… until her interfering brother-in-law Fred came into her life. He began to take control over her life, removing her from the school she adored, two terms before she was due to take her GCEs, so he could put her to work as cheap labour on his market stall.

One day, a kind neighbour stopped Veronica and told her she needed to get away, that she was nothing more than a little slave. “I knew in my heart it was true,” she says. “My neighbour’s comments struck a chord; they became a tipping point.”

Abused for many years by her father, then Fred, Veronica eventually ran away and applied to the Police Service, sensing that might be a safe place she could trust. “Women in the police force were few and far between in those days; it was, after all, still a male-orientated society… but the only alternatives for me were to be a bus conductor or work on a factory line, both jobs which I could learn in a week, after which boredom would set in,” she says.

Veronica was still under scrutiny from Fred, however. He turned up at her digs, and would stalk her; one night she was playing cards with friends, she caught a glimpse of something at the window out of the corner of her eye and realised it was Fred, peering in. An idea formed in Veronica’s mind. If she became a prison officer, there was no way he could come and interfere. “He would be locked out behind secure gates – and I would be, literally, locked in – and he would have no chance of being able to see what I was doing or who I was seeing,” she says.

Veronica was under no illusions that she was running away from the problem, but she took an exam at Askham Grange, just outside York, and was accepted into the Prison Service. Her first posting was a remand centre, Grisley Risley, near Warrington, where she soon noticed that many of the inmates were mentally disturbed. “I had landed in hell,” she says. Even then, Veronica harboured a belief that this was a long way from what a prison should be, but when she was posted on to Holloway, she found an even bigger hell.

“As I came to the end of my time there, I knew the future would lead me down a path of seeking ways to improve conditions, but I was fully aware I was still a trainee and not yet a prison officer with a voice,” says Veronica.

At a time when there were few women working in the Prison Service, Veronica applied herself to learning her new craft surrounded by many dangerous inmates. With no wish to go outside the prison, she remained inside on-duty while her colleagues went out to the pub, the theatre or to dine where she didn’t feel able to join them. Her dedication was recognised and she rose rapidly, moving from looking after no-hope prisoners on long-term sentences to ferociously violent men and coming up close to such infamous names as the Price sisters, North-East child killer Mary Bell, Rose Dugdale and Charles Bronson. The threat of riots was always only a step away, and escapes had to be dealt with quickly.

After becoming a Governor, Veronica was tasked with what was known within the Service as a ‘basket case’ - Brockhill Prison. However, with her diligence and enthusiasm – she managed to turn it around. “We bought duvets and curtains and enough paint so we could lose the green mire which dominated everything,” she says. “Lastly, importantly for the women, I put them all in clean clothes provided by the WI. Now they looked like women, rather than pantomime clowns in trousers too big for them.” It became a model example to the country, and she was recognised with an OBE from the Queen.

Veronica is still an active proponent of the justice system, continues to lecture across the country and is a supporter of Butler Trust, which acknowledges excellence within the prison system.

She has never married or had children; instead, she says the Prison Service has been her home and her family. “In the end,” she adds, “every one of us must do what we want to get the most out of life.”

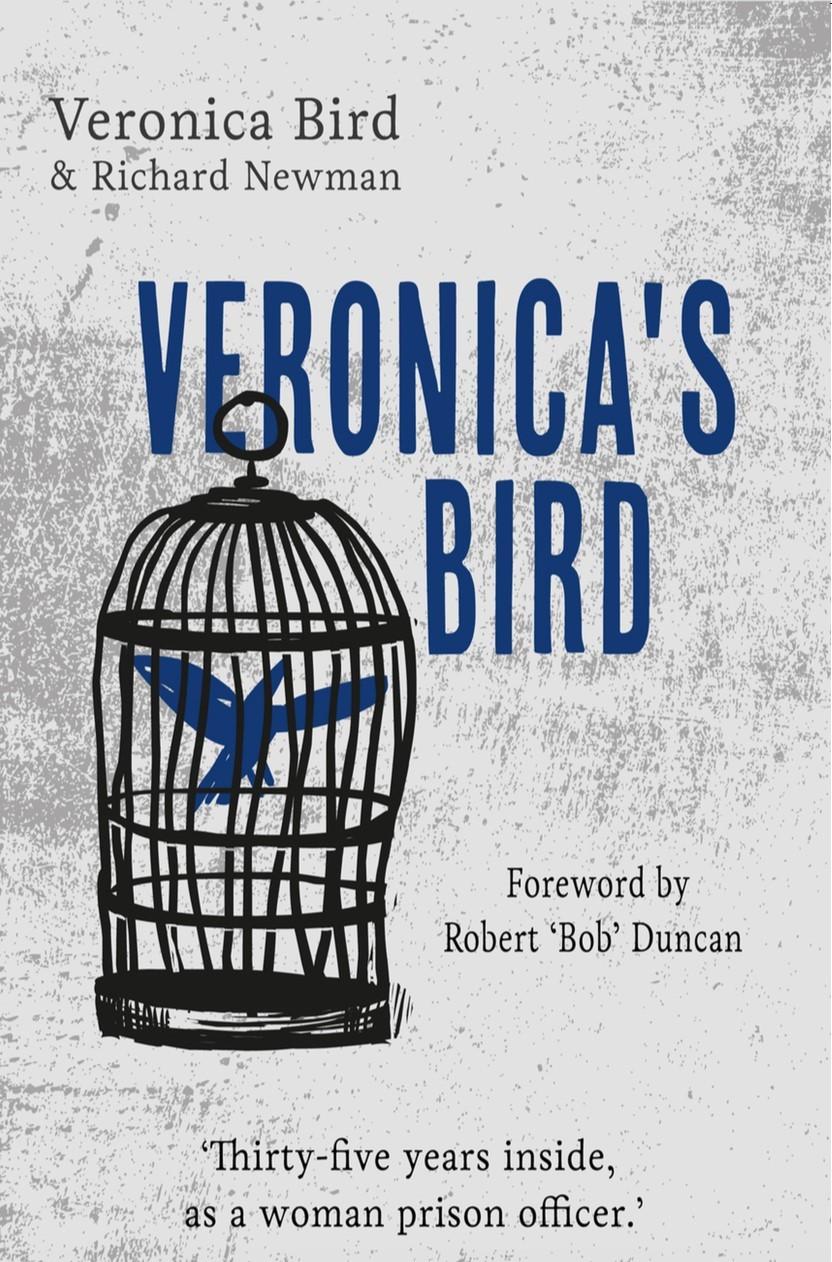

Ironically, for someone called Bird, Veronica found her freedom in a life behind bars.

n Veronica’s Bird by Veronica Bird and Richard Newman (Clink Street Publishing)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here