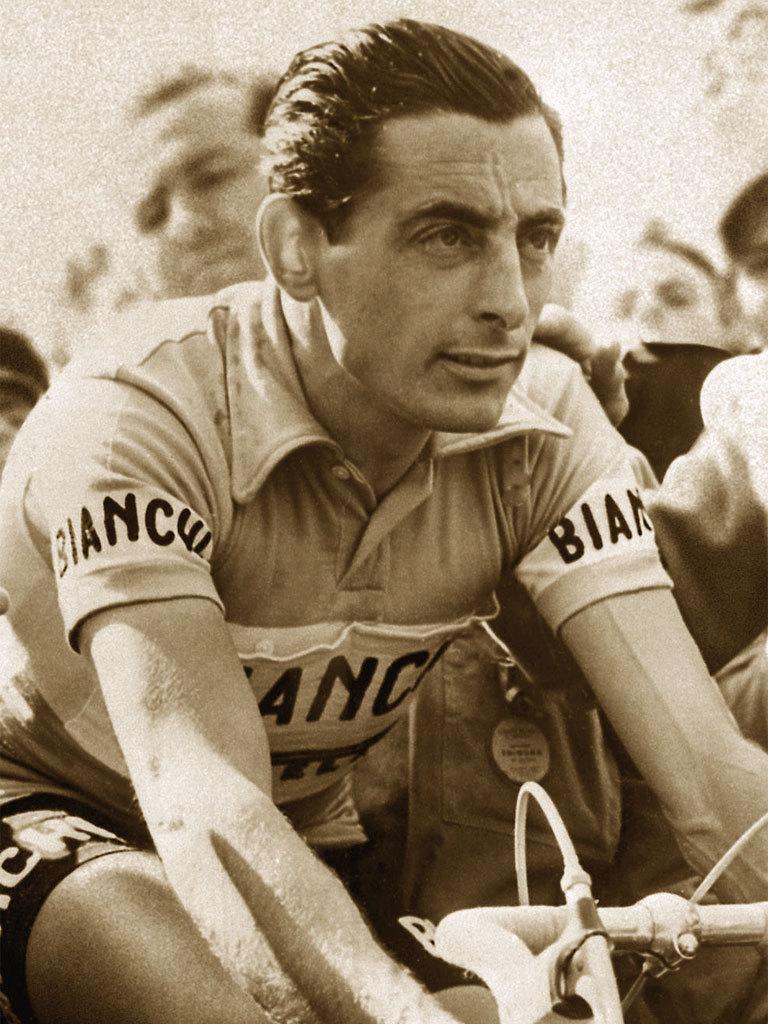

FAUSTO Coppi was a national hero who became the subject of a national scandal. As so often, it was a case of cherchez la femme (or whatever the Italian equivalent).

He was Il Campionissimo, the man they called Champion of Champions. She was Guilia Occhini, known as The Woman in White. The Pope personally urged Coppi to return to his wife, their landlord threw them out, the police raided their hotel room for evidence that they’d been sharing rather more than a bowl of pasta.

Italy was a much more strait-laced place back in the 1950s but Coppi, head over handlebars, had been smitten.

He was one of the world’s great all-round cyclists, five times winner of the Giro d’Italia, twice of the Tour de France and world champion in 1953. Many of his most epic races were against Gino Bartali, his arch-rival.

“A man who transcended sport, the stuff of legends,” says the Cycling Hall of Fame. A contemporary thought him “like a Martian on a bicycle,” though the source of his comparison is unclear.

Once he took the lead, none could catch him. Coppi, in every sense, was out of sight – so good that it’s said he’d sometimes stop for a coffee and still win comfortably, though coffee wasn’t Il Campionissimo’s only stimulant.

Long before Lance Armstrong pedalled his way into eternal notoriety, the attitude to amphetamines was altogether more relaxed.

Louise Riddell is so fascinated by it all that she wonders out loud if she might be in love with the guy. Last week, the 39-year-old mother of four opened her new coffee shop near the end of the C2C cycle route in Roker, Sunderland. It’s called Fausto Coffee.

Easter Monday, 11am. Though inland it’s a beautiful morning, Roker seafront is still fretful, the nautical fog horn mooing mournfully through the mist. The car parks are curiously full, the promenade curiously empty.

Looking remarkably spruce – not filthy lycra at all – North Tyneside Riders have already colonised the little coffee shop, about the size of a saddle bag, their bikes piled up outside.

On the wall there’s a blown-up image of Coppi and Bartali sharing a bottle of wine during a race – they even argued over who’d offered it to whom – on another wall a sort of topographical cross-section of some fearsome Italian pass.

North Tyneside Riders are discussing the relatively easier challenge of a dander through Boldon Colliery.

The magazine rack has copies of Cyclist and of Cycling and – rather more off the wall – Homes and Gardens. “I don’t want to marginalise my customer base, everyone’s welcome here,” says Louise. It’s only cyclists who get ten per cent off, though, and only those who’ve completed the C2C who got a free cake with their drink.

She worked for 16 years as a British Airways cabin crew member, then set up a pre-school music and singing business in Sunderland. Peter, her husband, is regional director of British Cycling.

“Over the years I’ve become quite smitten by cycling,” she says. “I never thought I’d hear myself say that but it really is one of those sports which consume you. You live it.”

She discovered Coppi while flicking through a book, noted a marked resemblance to her grandfather, decided to find out more. “I was just fascinated, his life is so full of scandal and sadness.

“There were times when he’d win a race by so much that they’d have to play music to the crowd while they waited for the second man to arrive. If it wasn’t for the Second World War he’d probably have been the greatest cyclist in history.

“There’s firm evidence that cycling is massively on the up and coffee drinking is massively on the up. The name just came to me. Fausto Coppi was fabulous.”

Coppi was born in 1919, a sickly, brittle boned and malnourished child who showed little interest in school. After truanting in 1927 he was given lines: “I ought to be in school, not riding my bike.”

The bike in question was a rusting wreck, his first real bike subscribed by a generous uncle when Fausto was 13. It cost 600 lira.

He won his first race at 15, the debut triumph earning 20 lira and a salami sandwich. In his first race as an attached rider he won an alarm clock – but Coppi was ahead of his time already.

“When Fausto won,” said a contemporary, “you just wanted to check the time gap to the man in second place. You didn’t need a Swiss stopwatch, the bell of the church clock tower would do the job just as well.”

He won his first Giro when only 20, set in 1942 a world one-hour record (45.798k) that was to stand for 14 years, had joined the Italian army and in April 1943 was captured in North Africa, becoming a British prisoner of war and camp barber.

Peace signed, hostilities resumed with Bartali. Bartali was devoutly religious, Coppi – as Pope Pius XII was to discover – had other gods. “Bartali prays when he is pedalling,” said an Italian sports journalist. “Coppi is filled with doubts, believes only in his body, his motor.”

Success continued despite about 20 serious bone fractures. Coppi’s stomach was said to be sensitive, too.

Bartali was also strongly disapproving of his rival’s drug-taking and would sneak into Coppi’s hotel room to check what his rival was on. “I became so expert at interpreting all those pharmaceuticals that I could predict how Fausto would behave and how and when he would attack me,” he claimed.

The Woman in White was married to an army captain, she and Coppi first setting adoring eyes one on another in 1948, apparently in a traffic jam. “Strikingly beautiful with thick chestnut hair divided into two enormous plaits,” said the French broadcaster Jean-Paul Olivier.

Soon they moved in together, permanently pursued by the press pack. His wife refused a divorce; a nation that had worshiped Coppi turned against him, spitting at him as he passed.

As his ability declined, so more greatly he turned to legal drugs. Criteriums were cut to 45k in an attempt to ensure that Coppi finished. In 1959, he and other riders were invited to Burkino Faso, where he contracted malaria. On January 2 1960, aged just 40, Il Campionissimo died.

Louise Riddell serves bread and hummus, a bowl of olives, a couple of Americanos. She looks again at the photograph on the wall. “What an athlete,” she says. “What a wonderful man.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here