IT is now almost impossible to make a Saturday train journey without being cooped – cackled?

– with a hen party. This one seems to have overdosed on the Paxo.

It’s the 8.30 from Darlington to Liverpool.

Fairy wings, bingo wings, they’re already necking copious amounts of frozen cocktails and still not entirely happy.

“It’s shocking,” grumbles one of the better prepared among their number, “£1 for a packet of sick bags.”

As is customary at this time of year, it should be explained that this is not the Railroad to Wembley – that’s the FA Vase – though it’s mildly coincidental that locals in the former Lancashire cotton town of Nelson know their football ground as Little Wembley.

Nelson are playing West Auckland, FA Cup extra preliminary round. At Leeds we get another train to Skipton, from Skipton a Burnley-bound bus across the perfect Pendle hills.

Mr Kit Pearson is also in attendance and, renowned for his serial disorientation, has thoughtfully put a compass in his jacket pocket the night before. Trouble is, he’s wearing his other jacket.

Nelson, for reasons which may not need explanation, are known as the Admirals. West Auckland are favourites: England expects.

NELSON is an old mill town of around 29,000 people, of whom around 40 per cent now have Asian ethnicity.

Multi-cultural evidence abounds. Shop window posters urge donations for Gaza or promote Muslim faith rallies. “Sisters will be seated separately upstairs,” they add.

It’s Saturday lunchtime and the streets are near-deserted.

The town seems anxious, almost atrophied, its Wikipedia page claiming that William Hill’s are now the only tenant of the Victory shopping centre. You wouldn’t bet on them staying much longer, either.

Outside the transport interchange, a poor chap is loudly threatening to destroy the world, apparently beginning with the bus queue for Barnoldswick.

In the Station Hotel, an aphorism above the television declares that “Reality is a state of mind created by lack of alcohol”, though what seems particularly unreal is that a pint of top quality Moorhouse’s ale is just £1.85. They have Holland’s pies, too, but there’s only one left.

Kit insists upon having an egg and cress sandwich instead.

That’s what mates are for.

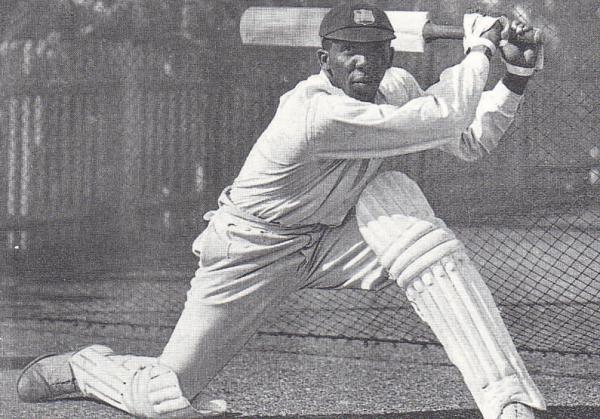

TWO of the Hollies were born in Nelson, someone from Life on Mars grew up there and there was one of the Hartleys, too. Much the town’s favourite son, however, was the magnificent Learie Constantine, a West Indian test cricketer who spent nine pre-war summers playing Lancashire League cricket for Nelson in the days when, like Chopwell, it was known as Little Moscow.

Those days are recalled in Harry Pearson’s splendid Slipless in Settle, a book about northern club cricket, chiefly because when Harry was an East Cleveland pub barman – the sort of boondock village where they threw stones at strangers, he adds, rather unkindly – Mrs Jessup, who worked in the kitchen, had been born and raised in Nelson.

“Mrs Jessup,” writes Harry – and this may not wholly be relevant – “had false teeth so pickled in dental whitener that in the twilight of a winter’s afternoon they seemed to emit an apocalyptic glow.”

Constantine signed for two years, stayed for nine, was paid £600 plus plentiful perks and at a time of maximum wage was reputedly Britain’s best-paid sportsman.

The club put up him and his family in a terraced house in Howard Street. An enterprising local, insisted Mrs Jessup, would form inquisitive townsfolk into an orderly line and charge them a farthing apiece to peer through the window.

Constantine, adds Harry, battled prejudice with charm and dignity. A more formal biography talks of “a compelling, magnetic and inspiring cricketer of extraordinary zest and dynamism.”

Known affectionately as Connie, he wrote books, broadcast, was called to the Bar, became an MP and minister back in Trinidad, returned to Britain as High Commissioner, was knighted and eventually ennobled.

He took the title of Baron Constantine of Maraval in Trinidad and Toabgo and of Nelson in the County of Lancaster.

FROM the Station Hotel we head down to the ground, more formally known as Victoria Park. The Hartlepool United team coach is parked outside. Either someone’s made a terrible mistake or West Auckland have been calling in favours again.

There’s a crisis: it’s barely 2pm and they’ve run out of beer. At an East Lancs derby four days earlier, it’s recalled, the bar only took £40 all match.

They’ve topped £40 within two minutes of the West Auckland supporters’ arrival.

Someone’s sent to the cash and carry, blue light job. The first chap returns with two carrier bags full of cheese and onion crisps, followed apace by someone else with cans of John Smith’s Smooth.

There are those of us who, in all honesty, would rather liquidise the cheese and onion crisps.

A further frustration, there are no team sheets because the photocopier’s dried up. “There’s not only no drink, there’s no ink,” says West stalwart Cliff Alderson, affably.

Though the pitch is pristine and the welcome warm, it’s perhaps a little difficult to see how Little Wembley serves its soubriquet, a residual mill chimney where the twin towers might have been and what once might have been a scrattin’ shed by way of grandstand.

The club also has a poet in residence, head of literacy at Bolton Sixth Form College.

Since “trembly” is the only word which properly rhymes with Wembley, she sticks to blankety-blank verse instead.

Wasn’t it Ossie Ardiles who first went to Wembley and discovered that his knees had gone all trembly?

Acknowledging the nickname, the FA had the previous week sent a people carrier to take four players and the manager down to Great Big Wembley to help launch this season’s FA Cup competition.

As Saturday turns out, it will be the closest they come to getting their hands on it.

NELSON was one of those clubs which made up the inaugural Third Division North in 1921-22, alongside the likes of Stalybridge Celtic, Darlington, Hartlepools, Ashington and Durham City.

In the first season they were 16th, at the second attempt they were champions. It was also the season in which they became the first English club to beat Real Madrid on Spanish soil, a victory of which Nelson remains proud.

Though they beat Manchester United at Old Trafford – doesn’t everyone? – they returned to the third division after one season, finished runners-up to Darlington the following year, attracted 14,143 for a match with Bradford Park Avenue in 1926 but four years later finished bottom and were thrown out.

On Saturday the crowd is just 168, half of them from Co Durham. The hosts take the lead, but West score twice in as many minutes, hang on a little anxiously and will entertain Darlington 1883 in the next round.

The little business with Nelson may be regarded as little more than a skirmish: the real battle awaits.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here