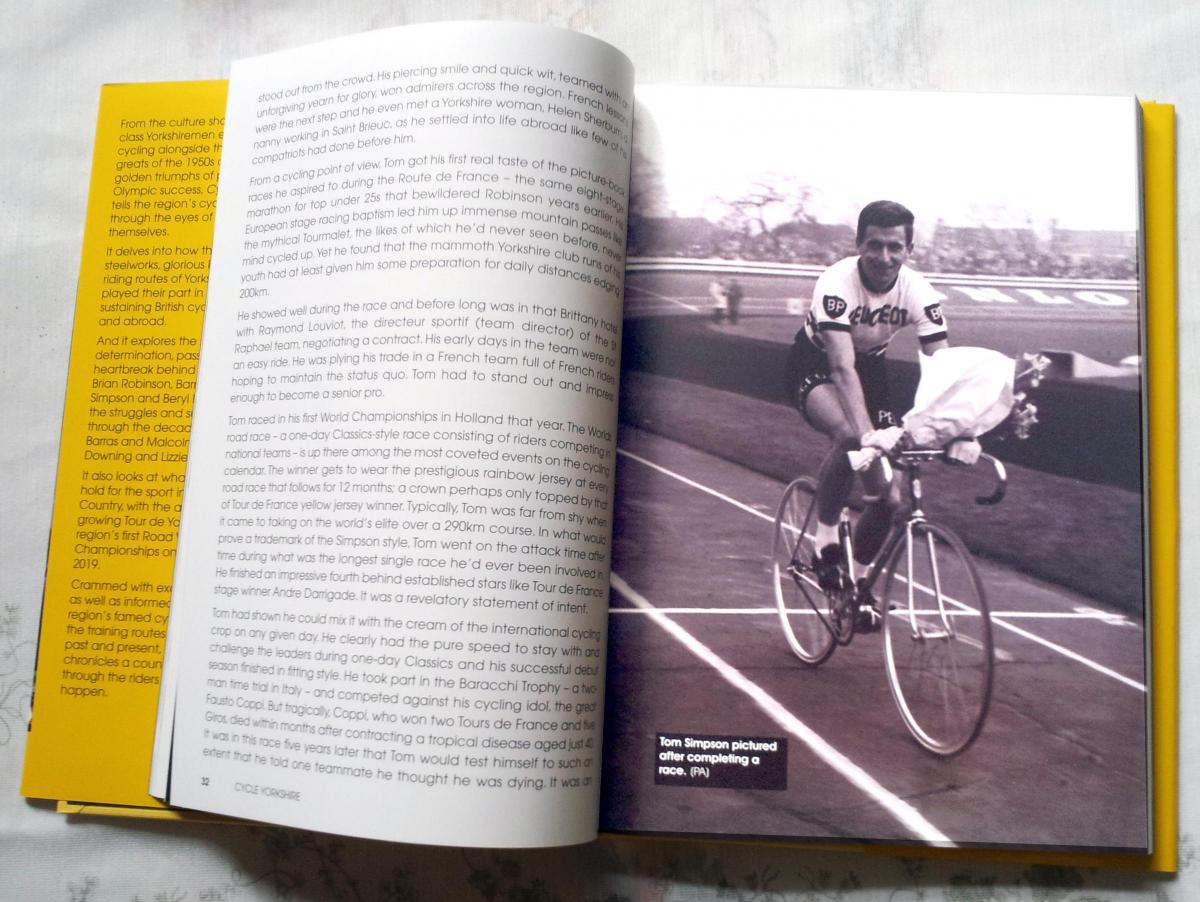

It’s 50 years this week since County Durham born cyclist Tom Simpson died while competing in the Tour de France. A new book, Cycle Yorkshire, by Jonathan Brown tells his story

Matt: It is 50 years this month since the death of Tom Simpson, how important a figure in cycling is he in the North of England and in the sport as a whole?

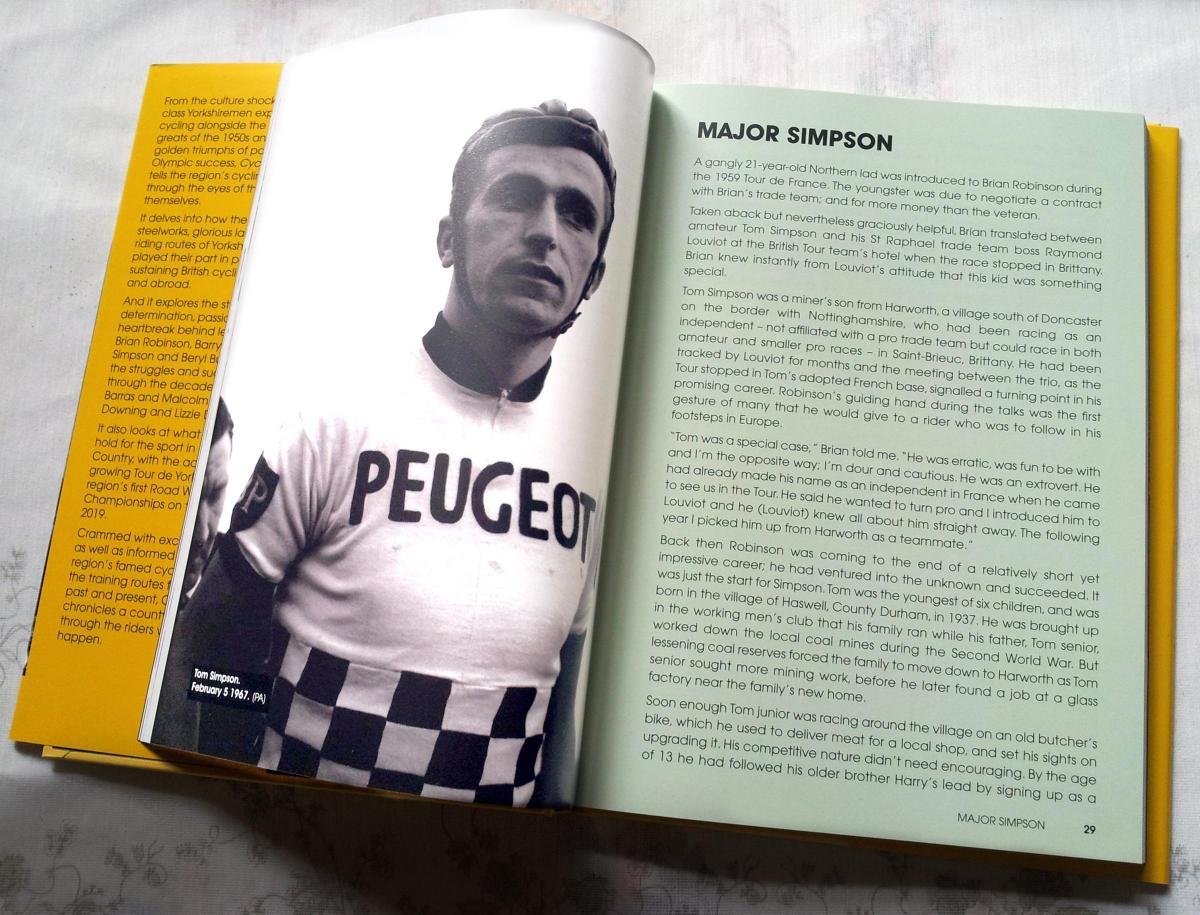

Jonathan: Tom Simpson was Britain’s first real cycling celebrity. He was the charismatic, approachable Sir Bradley Wiggins of his day, with a public image and persona to go along with his unquestionable talent as a cyclist – in fact he played up to the English country gent abroad stereotype that the French because he knew the value of it in terms of contracts and reputation. He was before his time in many senses – more than just a sportsman.

He became a cycling icon throughout Europe and at home, which was incredible in a climate in which road racing was in its infancy in Britain – he was the first cyclist to win BBC Sports Personality of the Year. He broke boundaries as a rider and inspired countless others to follow in his footsteps, after saving a few hundred pounds and packing up his belongings to travel to a foreign land and try to learn the language and survive. He was immensely important to the development of British cycling and his stock as a cycling legend, despite the manner in which he died, is still high across the cycling world.

M: Have his achievements have been rightly remembered by cycling historians and how does your book add to this legacy?

J: Yes, his achievements took decades to match and, seen in the context in which they were realised, it’s hard not to be impressed. Parts of his story, and particularly his demise, have been told and retold but I feel that my book, Cycle Yorkshire, adds an important backstory to what he did on and off the bike. It looks at his upbringing in County Durham and then Harworth in a mining family in which he was the youngest of six children, how the geography of those places meant he had the perfect training ground on his doorstep, how cycling was evolving in that period and how it had become a pursuit of the working class at a time of post-war petrol rationing. For me, looking at the wider story makes his journey more understandable. He wasn’t a molly coddled athlete who was molded into a world beater, he was a self-made man whose skillset was added to by his environment and who sought guidance from people he respected on what was a driven journey to the top.

Another aspect that I explore is how his achievements helped inspire and drive British cycling to bigger and better things, not just years but decades after his death. Sid Barras cites Simpson as his childhood hero, Sir Bradley Wiggins has praised Tom’s example throughout his career, while Tom’s 1965 rainbow jersey and a montage of his Road World Championship win were presented to Mark Cavendish and his GB teammates by British Cycling bosses in a bid to inspire them to repeat the feat in 2011 – and it worked.

M: Are his achievements in any way tainted by the use of drugs that were rife at the time he competed?

J: I think it’s fair to say that Simpson’s death made him a somewhat divisive figure. There will always be people who say he was a doper who won some big races but, like you say, he was competing in a different era. We’re talking about a time before drug testing, when some of the sport’s biggest names like the legendary Italian Fausto Coppi and five-time Tour de France winner Jacques Anquetil talked openly about the use of stimulants – in fact the latter famously said “you can’t ride the Tour de France on mineral water.”

The likes of his ex-teammate Brian Robinson, the first Brit to win a stage of the Tour, told me during interviews for the book that Tom had the ability to win big without drugs but that he simply wanted to win too much. Simpson saw himself as the best natural bike rider in the world at the time and he may well have been right, but his desperation to win cycling’s greatest race evidently pushed him too far. As time’s progressed I think the understanding of the drugs question has matured, and when you hear of Tom’s all or nothing approach – the stories of his dramatic crashes and spectacular blow outs – it becomes clear that this was an immensely talented yet flawed rider who achieved a great deal.

M: From speaking to those who knew him, what were his key attributes and how was he able to use these to his advantage in his chosen sport?

For a start, his contemporaries were in awe of Tom’s raw determination. Simpson wasn’t a specialist sprinter, nor was he a natural mountain climber, he was an all-rounder who managed to squeeze every ounce of potential from his pretty scrawny frame. In fact, he was nicknamed ‘Four-Stone Coppi’ for his pace and diminutive physique in his early days.

He thrived at hill climb events and time trials in Yorkshire and the North East as a youth and came to national attention with his raw pace on the track. That translated into an Olympic bronze in the team pursuit in Melbourne in 1956 at just 18. His career was an early template for today’s track-cum-road riders, and the stamina and pace he built there served him well on the road. His record – winning Classics like Milan San Remo – suggests one-day races were the format in which he thrived the most, but he always aspired to win stage races like the Tour de France, although his all-guns-blazing tactics probably weren’t best suited to the game of arithmetic that is the General Classification.

M: Assuming he had the latest technology, how do you think he would fare against today’s top cyclists?

J: It’s impossible to compare Tom with today’s riders, but the people I’ve spoken to are convinced he had everything to succeed in the present. Sid Barras told me Simpson was the best in his era and would be the best today because of his drive and natural ability. And in my opinion, Simpson would be one of the first to embrace the benefits of modern-day racing. He took on board and pioneered new ideas in areas like nutrition and the lifestyle you lead off the bike, so I don’t doubt that he would do the same with power meters and post-race warm down routines. He wanted to be the best that he could be, and given that he was at one time the greatest one-day road racer on the planet, I wouldn’t put it past Tom to be up there just as Sid suspects he would be.

M: It would be easy for some people to assume that cycling’s popularity in the Yorkshire area stems purely from the likes of the Grand Depart, but for how long has the region been associated with the sport and what part has it played in its development?

J: Cycling has well and truly boomed in Yorkshire, and in Britain, over the last couple of decades but this really is the latest chapter in a story that stretches right back to the 1950s. Yorkshire’s been a hotbed of cycling talent ever since Brits discovered the thrills and spills of road racing in the early 21st Century. The terrain in Yorkshire has a big part to play, as do the down-to-earth, working class communities geared around the mines and steelworks that made this part of the country so important in terms of industry. In the early days Brian Robinson, Tom Simpson, Barry Hoban and their female counterpart Beryl Burton were all products of working class endeavour and a love of cycling that was inflamed by the undulating hills and beautiful countryside the North of England has been blessed with.

It’s been far from plain sailing, though. Since their early forays, cycling experienced surges and lulls in popularity nationally, and the perception of British riders wavered and strengthened but throughout those periods, Yorkshire has been a mainstay in terms of producing riders capable of mixing it with the best. The Grand Depart was incredible, but it was the tip of the iceberg in terms of Yorkshire’s cycling story.

M: What is it about the region that makes cycling so popular here?

J: For me, it’s a combination of heritage and nature. If you talk to or read into the likes of Barry Hoban or Brian Robinson, or fast forward to Russ and Dean Downing, Dave Rayner or Ben Swift, a lot of these people came from not just working class and hardworking areas, but from cycling families and cycling communities. The sport’s been the bedrock of some parts of the county since the early post war time trialing days, and that passion for the sport has been passed on from generation to generation. Beneath that you have natural terrain that is perfect for cycling, with fearsome hills and undulating roads that carve their way through our national parks and along our coastline. Those two aspects have become intertwined over the decades, and when Sir Gary Verity hatched a plan to bring the world’s most watched sporting event here, he stumbled upon that gold mine – a stroke of luck/ genius that he acknowledges in the book – and brought it to the attention of a global audience.

M: As a cycling fan, what was it like speaking to the likes of Brian Robinson and Sid Barras when you were putting the book together?

J: The men and women I interviewed were and still are legends of the sport, not just in British terms but internationally, and it was a privilege to speak to them. Brian and Sid are good examples as well, because they encapsulate the rough ride the region’s cyclists have been on over the years. Brian’s stunning achievements went largely unappreciated for years back home whereas Sid was one of the first real stars of British cycling’s domestic scene following the televised Kellogg’s races of his heyday. They both witnessed the sport’s doping darkside, and, for Sid, seeing drugs in the sport in the early 1970s made him come home and abandon the continental dream.

Obviously cycling’s changed immeasurably since then, and to talk to Ben Swift about how his family’s love for cycling inspired him, and also how the British Cycling talent spotting empire unearthed talent more by chance than through inheritance, like in the cases of Lizzie Deignan and Ed Clancy, was equally fascinating. To hear, first hand, how many of these people came from nothing to compete on the world stage was unbelievable and I hope that I’ve captured both the triumphs and struggles of their careers in a way that does them justice.

M: What is being done and by whom to ensure that cycling remains as popular as it is now in the years and decades to come?

J: The reality is that in years gone by, the likes of Brian Robinson were underappreciated. He told me that he left his beloved sport as a Tour de France pioneer on a Saturday and walked into his old life as a tradesman on the Monday and “nobody knew any different”. The romance of the Grand Depart shone a light on a story starring Robinson, Simpson, Hoban, Burton, Barras, Rayner, Walker and countless others, and it’s brought about an appreciation of our collective history that I’ve tried to explore in Cycle Yorkshire. The history is something we should be proud of and continue to build on.

Welcome to Yorkshire and Sir Gary are certainly doing their best to do that. In the book he spoke to me about his passion for staging these big events, his desire to expand the Tour de Yorkshire to four days and his plans for the Road World Championships in 2019. The worlds will be huge for the entire region, and the closest thing yet to replicating the Tour de France, which coincidentally he wants to bring back here. From what I can gather, this man won’t stop until Yorkshire’s considered to be among the world’s top cycling destinations – and I wouldn’t put it past him.

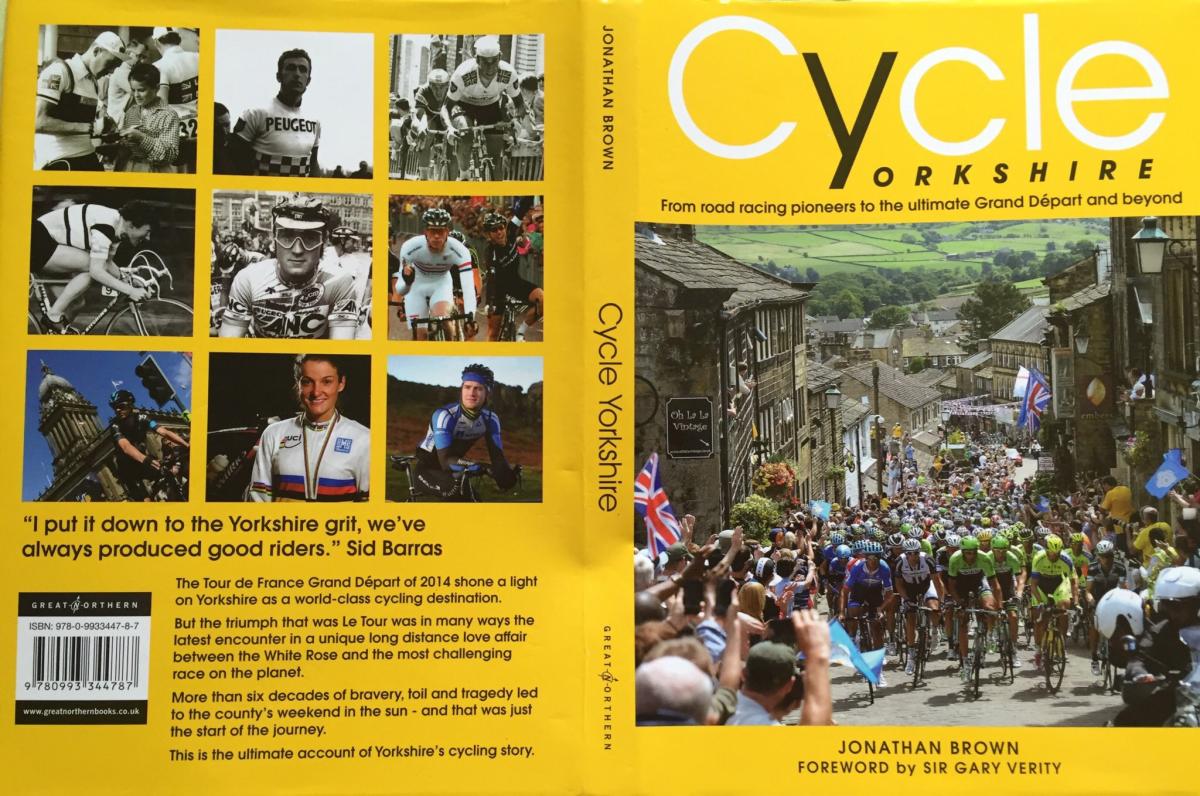

- Cycle Yorkshire by Jonathan Brown, published by Great Northern Books, is available for £17.99. ISBN: 978-0-9933447-8-7. Available from www.greatnorthernbooks.co.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article