VERY likely it’s the case, as Mr Noel Coward supposed, that only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the noonday sun. They and itinerant columnists, anyway.

Thus it was that, shortly before 12 last wipe-out Wednesday, we set out from the Swaledale village of Healaugh along the steep and rugged pathway to the pub.

As Coward observed, the English detest a siesta.

Healaugh’s a charming little place, said in Ella Pontefract’s classic 1934 book on the dale to have a “peaceful but rather mournful air, as though it remembered former greatness”.

Though clearly she loved the dales, Miss Pontefract – as her name suggests – was a West Riding lass by birth.

The byroad rises empty, silent save for the sheep, to the ruins of the Surrender smelt mill a couple of miles away. Notices advise that the ground nesting birds have European special protection, others tell of sites of special scientific interest.

Another area’s not only identified as a dog exclusion zone, but (it says) patrolled by wardens and covered by video surveillance.

It’s inapplicable. Nothing, not even the wag-tailed aphorism about not having a dog and barking yourself, would ever persuade me to have one. Nor a puss cat, either.

The Surrender Leading Mining Company, inexplicably named, prospered mightily in the 19th Century, working conditions most kindly described as Victorian.

A large notice in the Swaledale Museum, down dale in Reeth, advises that boys between 12 and 16 must work no longer than 54 hours a week underground, or more than ten hours a day.

The smelt mill’s a listed ancient monument, the moors more wondrous yet. On the road to Surrender just a single vehicle passes, though there’s a little flotilla of white-van-men – mostly of the DPD genus – as it turns north towards Arkengarthdale, and Langthwaite.

Footpath signs point towards places like Little Punchard and Gill Head Moss, a footbridge across a ford featured in the opening sequence of All Creatures, a set of rugby posts rests against a remote farmhouse wall.

Goodness knows where the skipper gets the other 29 from, or a couple of touch judges, either.

The road drops sharply to Langthwaite, a tranquil spot where Rowena Hutchinson has for 54 years run the Red Lion, a gorgeous little pub, without ever once whetting her whistle.

Up there, says Rowena, they’ve not had a drop of rain. Springs have dried, distant farm are without water.

It’s touching smugness to report that the Black Sheep was in fine fettle, that a good pork pie and a smidgeon of mustard is the only food that a proper pub needs and that the six-miler, though oft-vertiginous, is utterly glorious.

As Noel Coward might have observed, mad for it.

THE lady, up to Langthwaite in the car, has called at the Swaledale Museum en route and is keen that we return. It’s a smashing little place, vividly illustrating how greatly dales life has changed.

Particularly she’s taken by the poster for the first Reeth Show, in 1840, when the first three prizes went to the lead miner who’d brought up most children under ten without recourse to the parish and only by the fourth did they get round to the best tup.

Should we, she wonders, let them have a cutting of the memorable Sunday morning in 1986 when three times in an hour they called for Reeth fire brigade, though never once to a fire.

A little more about the Swaledale Museum in the next week or two. Suffice that it’s open every day from 10-5pm – free to under-12s, price of a pint to their elders and absolutely lovely.

ANOTHER of our favourite walks is the seven-mile round trip between Wolsingham and Frosterley, alongside the river and the railway. Half way, pint in the Black Bull, we look into Frosterley Co-op for a copy of the Weardale Gazette, edited by that most ardent and celebrated of royalists Anita Atkinson. The Co-op’s sold out, but at 5pm there’s still a copy of the Morning Star, mouthpiece of the Communist Party of Great Britain. God save the Queen.

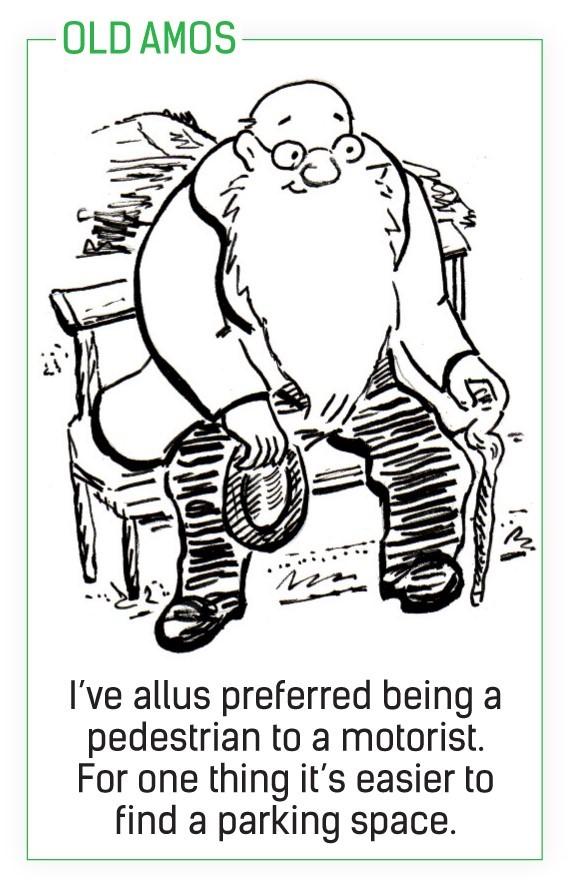

AMID all this hoofing about the hills, there was a wonderfully appropriate Old Amos cartoon in the July issue of Dalesman magazine – reproduced with permission of the magazine and of Peter Lindup, the artist. Dalesman editor Adrian Braddy reports that the hirsute sage has just passed his 65th anniversary in the mag, making him eligible for the pension. He’s still the youngster of the family – but as usual, he’s right.

BY train, inevitably, we head last Saturday for the 175th anniversary celebrations at Bishop Auckland railway station, and no matter that it was really opened in January 1843.

“A little white cottage and a water pump,” says railway historian Gerald Slack, though the station – in its steamy prime four platforms with a triangular lay-out – was to see much headier days.

Efforts to promote both Bishop and its railway are enthusiastically pursued of late, not least through the efforts of the Town Team and its secretary Clive Auld, a long serving former polliss in the town.

Clive’s originally from Wearside. “I’m a Sunderland lad when the football team’s doing well and a Bishop lad when they’re not,” he said.

Most of the time, added Clive, he was a Bishop lad.

There, too, was the tusky Bishop Boar, one of the burgeoning breed of mascot-monsters first seen on football grounds.

Lest anyone be homophonic, Bishop Boar has his name spelt correctly over his expansive stomach – but, honest, the old place is much enlivened these days.

BACK on the buses, Peter Chapman draws attention to a website thread on “underrated bus routes.” Among those extolled – “great bomb along the old A1, various diversions through 1950s new towns and former colliery villages” – is the No 7 from Darlington to Durham.

It’s one of Arriva’s Sapphire services – “making your everyday journey sparkle” it says on the side of the bus – and takes an hour-and-a-quarter.

We happen to be on it last Friday, at least as far as Thinford – ever-fattening Thinford – the experience little enlivened by two women intent on discussing fallopian tubes.

The friendly driver refers to his double decker as “her". Much more, and he’ll likely propose holy matrimony to it.

The journey to Thinford takes 58 minutes, the first 15 spent slipping the surly bonds of Darlington, another 15 on a circumnavigation of Newton Aycliffe, that well known 1950s new town. If the bus seems a bit slow, it can’t be said that the pulse is exactly racing, either.

What’s that they say about familiarity?

It has 17 minutes to get from Thinford to Durham bus station. Old Amos walks down to Spennymoor instead.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here