THOUGH unavailable on the NHS, and thus £4.25 a month, advancing years allow incontrovertible allegiance to a magazine called The Oldie.

A feature in the December issue is headed “Whatever happened to Dr J Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne?” and in its wake trails a scant-suspected subplot.

It’s about the occasion that the good doctor not only saved the village of Trimdon, but won a gold medal for his pains – or, at least, for alleviating theirs.

John Collis Browne, his name once on every pharmacy stock list and his “mixture” still on sale, was a doctor with the Indian Army when, around 1848, he formulated Chlorodyne, said chiefly to be effective in treating cholera.

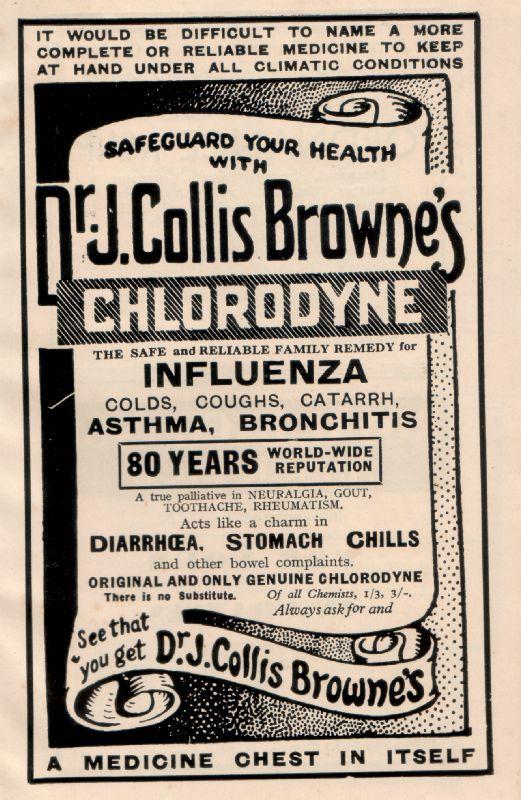

By the early 20th Century, its countless curative claims ranged from colds to croup, diarrhoea to dysentery and from flu to flatulence.

Since its principal ingredients included chloroform and cannabis, it was perhaps unsurprising that the stuff was said also to be good for insomnia.

Back in Blighty – dates are inconsistent, but early 1850s – Collis Browne was asked urgently to travel to Trimdon, a pit village in east Durham, where a cholera epidemic raged.

Though Collis Browne isn’t mentioned, a contemporary account on the Trimdon Times website supposes the outbreak to be “very fatal” – as opposed, presumably, to just mildly fatal.

At least 14 had died, another 40 or 50 were affected by the disease “in a bad form”, among the curious things that none of the surrounding villages appeared affected.

Trimdon was said principally to be on a hill and thus “rather favourably placed for sanitary arrangements, though there is a burning and sulphurous pit heap not far from the row”.

The disease, the account added, had been most fatal (here we go again) among the least prudent – “and hence the poorer portion of the pitmen, though temperate right living persons have been victim to it also”.

Though the pit surgeon and his assistant had done their best, they sent for the good doctor and his medicinal compound, the treatment so efficacious that Trimdon struck a gold medal – “a testament to his humanity, skills and ability during a visitation of cholera in 1854”.

Dr Collis Browne died, aged 65, in 1884. Whatever the cause, it probably wasn’t cholera.

SIMILAR symptoms, John Collin Browne was last mentioned hereabouts in 2002, an ad for Chlorodyne illustrating a book by Wensleydale lass Dulcie Lewis on traditional cures and remedies.

That, in turn, prompted David Walsh – then leader of Redcar and Cleveland council – to recall that in the 1960s it was much used by hippies.

“There was a huge rush by characters with twitchy eyes, Afghan jackets and droopy moustaches. I remember a picture of a pop festival with people lying on their backs shoving bottles of Collis Browne’s chloroform down their throats.

“I don’t know what else it did for the hippies, but I bet they weren’t half regular.”

Fifteen years on, David can’t remember it. “I wonder,” he says, “if Collis Browne’s works for memory loss, too.”

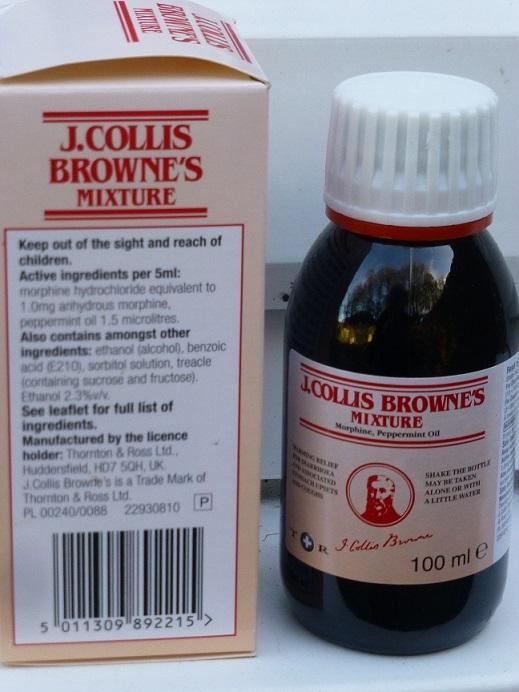

AFTER diligent searching of which the Magi themselves would have been proud, we find a 100ml bottle of J Collis Browne’s Mixture – £7.02, or £7 for cash – at a little pharmacy in Richmond.

“None genuine without the name of J Collis Browne” it says on the side of the box, though these days the stuff’s claims are more modest.

“Warming relief for diarrhoea and associated stomach upsets and coughs,” it says, the chief ingredients listed as morphine and peppermint oil. An accompanying leaflet details all manner of caveats, including the doubtless sensible precaution of not taking it while unconscious.

It was the last bottle; the lady in the shop said they wouldn’t be getting any more. If there’s a cholera outbreak in Richmond, they’ve had it.

RECORDING the opening of the Mining Art Gallery in Bishop Auckland, the column a couple of weeks back recalled a Spennymoor painter and decorator who in his spare time was an artist who’d give his broad brush customers a painting for Christmas.

We said he was called Robert Dodds. “Did you mean Bertie Dees?” asks John Yeomans, gently, and undoubtedly it is so. “He was rarely seen without his dust coat and trilby hat except when treading the boards at the local operatic society,” John adds.

George Courtney well remembers him, too, grew up a couple of streets away in Low Spennymoor. “His living was painting and decorating, but his passion was art, often seen painting woodland in what’s now called Cow Plantation or encouraging young artists at Spennymoor Settlement. I don’t think he got the plaudits he deserved.”

LAST week’s note on Eddie Roberts’s funeral in Richmond reported that his musical repertoire ranged from the Welsh national anthem – that, particularly – to I Thought I Saw a Pussy Cat. Wendy Fellows, rightly, suggests that the correct title is I Tort I Taw a Puddytat – which is how it was pronounced in the eulogy. “I can hear Tweetypie singing it now,” says Wendy, “but I bet Eddie’s rendition was better.”

DAVID WILBOURNE, mentioned a couple of weeks back, was vicar of Helmsley, in North Yorkshire, before becoming assistant bishop of Llandaff, in south Wales.

The At Your Service column encountered him in 1998, pedalling an “essentially ecclesiastical” bicycle to morning service at East Moors church, four miles north of the town.

The bike was something called a Raleigh Jaguar, and in British racing green to add lustre. “I tell people I drive an open top Jag,” he said.

Now back in North Yorkshire, agreeably close to the cycle path that was the Scarborough to Whitby railway, Bishop David has been in touch.

Prolific writer and himself a son of the vicarage, he recalls his father’s 16-week confirmation classes – “long and boring”.

David’s were different, he, his wife and 14 youngsters re-enacting the Last Supper – “flat bread and a little wine” – beneath the kitchen table.

“We pretended we were in the catacombs,” says David. “Safeguarding would have had a fit.”

MARTIN BIRTLE, who watches television with sub-titles, reports a programme last week about how Hadrian’s Wall was built to keep out the barbarians. Words had a think and translated that it was to keep out the Bavarians. “I thought,” adds Martin, “that that’s why we had Brexit.”

...AND finally, The Times reports that acerbic columnist and broadcaster Rod Liddle was left high and dry in the buffet on Darlington station two Sundays back.

Liddle, raised in Guisborough and now back in east Cleveland, arrived at 11.55am and asked for a glass of white wine. The girl said she wasn’t allowed to serve alcohol until noon and, despite protestation, remained obdurate.

On the stroke of 12, he rejoined the queue and again asked for white wine. “Sorry,” she said, “we haven’t any.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here