RICHARD GAUNT sends a couple of his books, insists that he’s not seeking publicity, earns it anyway. To ignore them would be dereliction: wonderful Christmas presents, these photographic essays of North-East England in the 1960s are a unique record of how the region has changed.

“The publisher will be pleased,” he says.

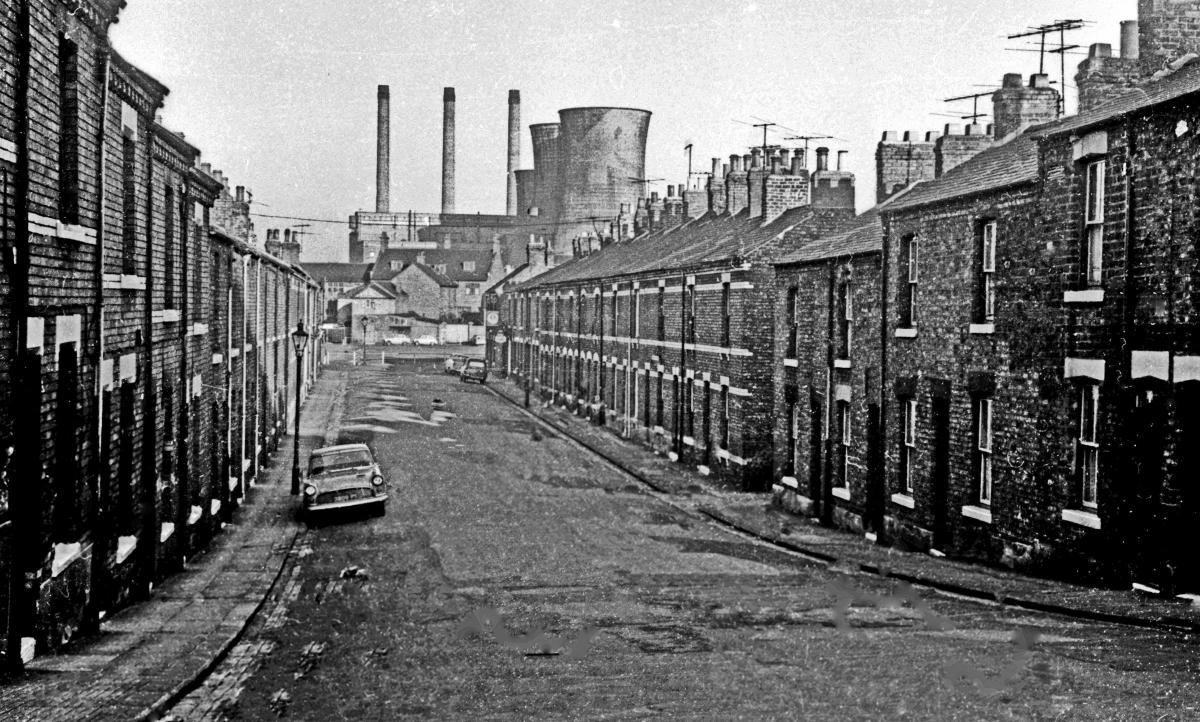

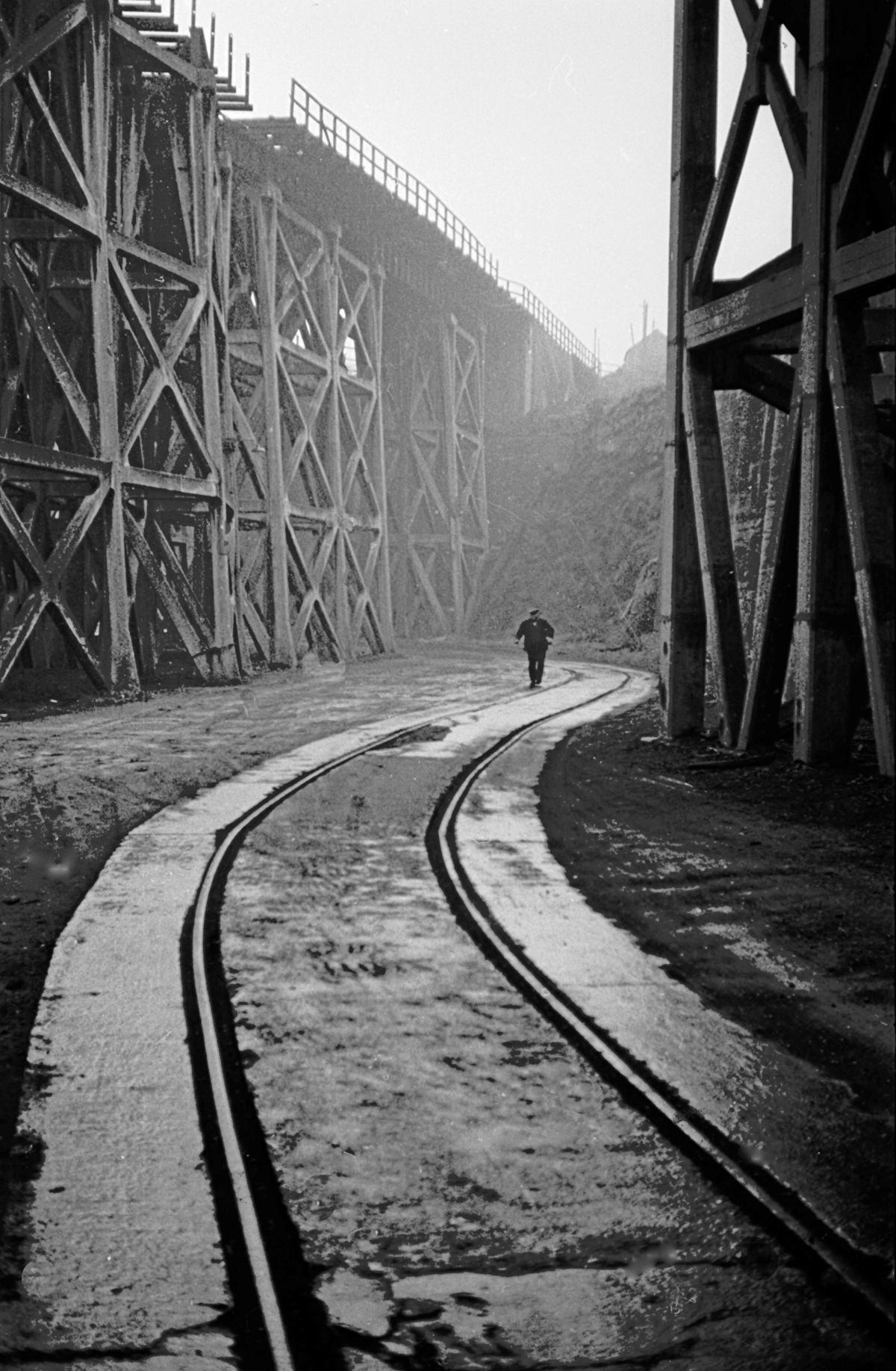

There are, of course, any amount of books of old picture postcards and all with pretty much the same stamp. These are wholly different, the region in black and white and never has monochrome more vividly told a tale.

Exclusively and extensively, they were taken by Richard during his teenage years in Darlington in the “vague belief” that the old order might be on the edge of epochal upheaval.

Without recourse to a dark room, he developed the 35mm film in a sleeping bag in the lights-out kitchen – “a mystery for those who’ve never tried it” – consigned the negs to a suitcase. There they stayed, surviving several house moves, for almost 50 years.

Often he’d get around on his push bike, later on a motor bike variously described as “flimsy” and “dismal”. Often he was drawn to the doomed steam railway, often to fog and snow. Often he didn’t have far to look.

The first book concentrates on Darlington and west Durham, the second on the North-East coast, allowing him to venture as far south as Whitby and to take pictures from the top of the Transporter Bridge (a vantage point to which he is greatly welcome.)

Both speak of a different age: those were the days of cranes and corner shops and kids playing in the back street, of clothes lines and Category D, Double Diamond (which worked wonders) and, manifestly, of pollution.

Richard’s wary of stereotypes, insists that he’s not trying to say anything – “either momentous or sentimental”. It’s the positives, not the negatives, which are accentuated here.

NOW 68, he was a Darlington Grammar School boy, played rugby, supported the Quakers, recalls that they had a dentist – and so they had – at centre forward.

Having won a place at Cambridge, he worked in the labs at ICI Wilton, discovered both the dubious delights of the ICI spam fritter and that he wasn’t a natural scientist, worked thereafter on the A1 motorway site through County Durham.

The great north road was completed on time, as was the resurfacing of a number of garage drives in the Sedgefield area.

After switching to economics at university he moved to Cardiff, became the city council’s head of corporate services, remains in Wales, takes – he insists – fewer pictures, but with more care.

The books are a careful running commentary, too, but if ever a picture was worth 1,000 words, it’s here.

DARLINGTON – “in a lot of ways a different world” – features prominently. There are tremendous pix of the 1967 Durham Miners’ Gala at which Harold Wilson kept dry in his Gannex, some lovely studies of the dying days of the old Bishop Auckland railway station – “barrows long after you were able to find a porter to push them”.

There are wonderfully evocative shots of industrial Teesside, some smashers of Seaham, where pits and privies emptied into the sea, and than which few places may more greatly have changed (and, very likely, for the better.)

He’s also strong on sheds “place where men had Very Important Things To do”.

For some, of course, they were the swinging sixties; for others, the bad old days. However clouded the skies, however recycled the images, these are a breath of fresh air.

n Richard Gaunt’s books of images of the North-East in the 1960s Durham, Darlington and County Durham and Industry and the Coast, are published by Fonthill Media at £17.99, but are also available, discounted, on Amazon.

IT is to be a books page. A volume simply called Gresley’s A3s comes gently to a halt.

The A3s were (of course) steam locomotives, a class of 78 familiar to us smutty-faced kids waiting with dog-eared anticipation at the business end of Shildon tunnel for something unexpected to turn up.

All had names, mostly borrowed from racehorses, though we always wondered how 60039 – Sandwich – came by its cheese-and-pickle plate.

60100 was Spearmint, 60085 was Manna, though whether from heaven or from Gateshead shed it was impossible to say.

Peter Tuffrey’s 128-page book has memory stirring images of every one of them, frequently burning up the East Coast main line, and a special section on The Flying Scotsman, the best known of them all.

n Gresley’s A3s, Great Northern Books, £25.

GERALD SLACK, that indefatigable railway historian, has privately published a 24-page booklet – an “illustrated essay”, he modestly calls it – called Shildon: the World’s First Railway Town.

It records the fact that Shildon tunnel – “a major feat of engineering,” says Gerald – was opened 175 years ago next April. Still in use, it’s 120ft below the dear old town, 1,225 yards long, contains an estimated seven million bricks and cost around £120,000.

On opening day the gaffers were wined and dined at the Cross Keys, across the road from one of the ventilation shafts, while the workers caroused in six other pubs in the town.

Though the Cross Keys is long gone, something really should be done to mark the anniversary. These men bored for England.

...AND finally, another early Christmas present returns us once more to the birthplace. A reader sends Stop the World I Want To Get Off, the seventh annual collection of unpublished letters to the Daily Telegraph.

Since on busy days the paper still gets more than 1,000 letters for possible publication, that’s clearly most of them.

Among the best of the rest is one from Dr Bertie Dockerill in Shildon, though whether a medic or one of those clever folk with a PhD is uncertain.

We’ve encountered him before, again in the Telegraph, lamenting the changed recipe for Cadbury’s creme eggs – “an outrageous affront to the nation’s cultural heritage”.

Whatever his qualifications, Dr Dockerill is clearly one of those folk sceptical of the rash of dietary warnings. “It would appear that whatever I eat or do not eat, one day I shall die. In the meantime I shall continue to eat sausages. It is unthinkable for an Englishman not to do so.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here