IT'S six months since Mike Hoban died, a sadness which coincided almost exactly with the demise of his beloved Houghton-le-Spring cricket club. Jon Grant’s greatly affectionate tribute has just arrived – “as the 2017 cricket season reaches its conclusion,” it begins….

It was through football, not cricket, that we were first acquainted. Neil, Mike’s son, had several seasons with Shildon in the 1990s, his dad faithfully on the sidelines.

He’d been with Houghton since the 1970s – secretary, opening bat, much else – for most of which time the club hadn’t even a ground to call its own. Mike worked miracles to keep the club alive, says Jon.

They finally returned to Houghton in 1987 and joined the Durham Coast League two years later – a season in which Mike, then 43, hit his maiden century.

He retired from playing in 1990, watched his side lift the league title and then oversaw an outstanding season in 1992. “For a spit and sawdust organisation, Houghton had claimed a place at cricket’s top table,” says Jon.

Neil and his brother Graham also played – Graham for nigh-on two decades, Neil briefly but flamboyantly. Family club, Mike’s wife Jean and her sister Maureen made the teas.

“It’s still conceivable,” says Jon, “that many of the inhabitants of Houghton-le-Spring were aware that we even had a cricket team.”

Mike left Houghton in 1995, became secretary of Philadelphia and was particularly fond of the Bunker Hill ground. “It’s nice and compact. You can hear the batsmen’s arses squeak as they go out,” he once observed (in print.) He was also at Eppleton.

“The local cricket scene has lost one of its finest ambassadors,” says Jon Grant. “Perhaps it is worthy of note that it needed someone who came from Pity Me to give the community of Houghton-le-Spring something of which to be proud.”

MIKE Hoban most memorably featured hereabouts in September 2000, recalling the second battle of Bunker Hill while seated around the blazing fire in Philadelphia’s restored cop shop.

The original police station had been in an outhouse in Shop Row, its sliding window opening onto a world of mischief and miscreants.

“The place,” observed Colin Bertram, “where the sergeant chewed your lugs off.”

Four of us were gathered – the column, Mike, Colin and David Tindale, a retired organ builder who’d restored the nick to museum-piece splendour and who lived in the house down the yard. House and police station survive yet.

Bunker Hill was a battle in the American War of Independence. The second battle broke out on August 31 1912 when Philly hosted South Shields, Durham Senior League, in what might have been supposed a grudge match but was much more volatile than that.

At its black heart was Philadelphia wicket keeper John “Kellett” Kirtley, a bibulous and belligerent character who’d claimed 116 victims, almost half stumped, in 84 appearances for Durham County.

Space precludes a round-by-round resume. Suffice that there was a bit of class warfare about it – Philly the miners, Shields the merchants – that Shields captain Tom Coulson thought it “more like a scene from a lunatic asylum”, that Shields historian Clive Crickmer wrote of “fury never witnessed on a scale before or since” and that Kellett Kirtley led the mob.

“A riot, no doubt about it,” said Mike Hoban at the time.

Kirtley was banned for life both from the league and from Bunker Hill, Philly were fined a guinea and had two points deducted, Shields censured for refusing to bat and fleeing for Penshaw railway station instead.

The league later gave Philadelphia their guinea back – “to show the true spirit of sportsmanship.”

Approaching its 150th anniversary in 2018, the club was said last week to be preparing a sesquicentennial history. Coals of fire, the events of August 31, 1912 will no doubt again be resurrected.

SO far as may be seen, Mike Hoban only once had a letter in Hear All Sides, All Saints Day 2004, concerning shamateurism both in Northern League football and in local cricket.

“Half-time oranges on the balance sheet of some clubs exceeded the Mexican national debt,” he wrote.

The same thing was happening in cricket, said Mike, putting further pressure on fund raisers. “We should go back to basics and tell the Pyramid and the rest of the world to go and whistle.”

The letter was headed “Crying sham.”

PERHAPS the longest gap between death and obituary – rather the opposite of a gestation period – followed the passing of former test match umpire Tom Spencer.

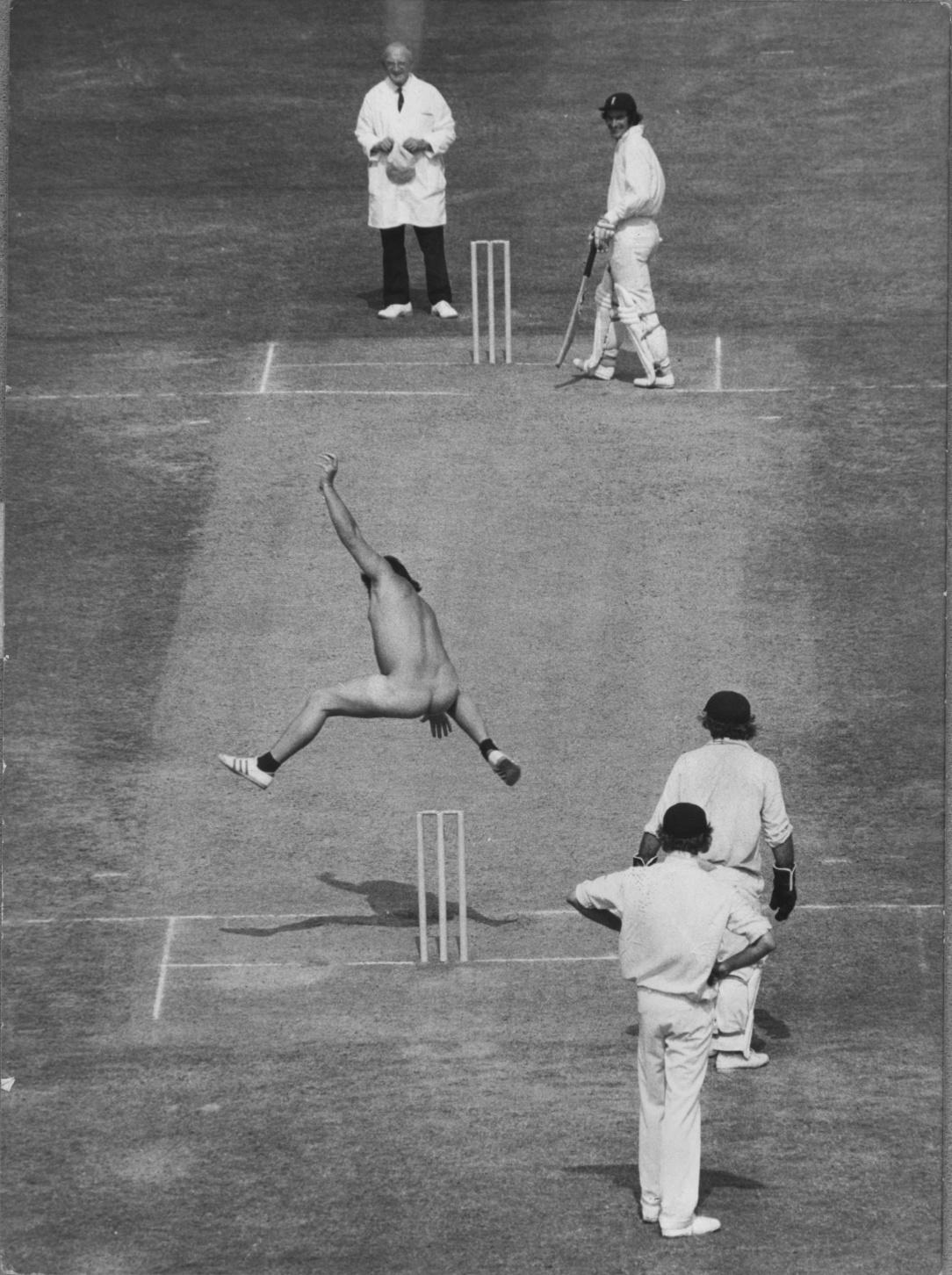

Tom, a delightful chap, was a man of Kent but had long lived at Seaton Delaval, north of Whitley Bay, where his wife’s family had run the chip shop. Known for what Wisden called a “gummy smile”, he was officiating at a Lord’s test in 1975 when a gentleman called Michael Angelow made an unscheduled appearance wearing only a pair of socks.

Mr Angelow later wore a policeman’s helmet though not, it may be recalled, on his head.

We’d interviewed Tom in 1990, he still in the habit of taking a photograph of the Lord’s streaker to show the lads at Seaton Delaval club. “It gives them a bit of a laugh, they never seem to grow tired of it,” he said.

He died, aged 81, on November 1, 1995. Six days later the column published an affectionate tribute.

It was thus a bit of a surprise, in January 2003, to field a succession of calls from cricket cognoscenti asking if we were quite sure that Tom was no longer with us. Hadn’t there been a funeral service at Earsdon Avenue United Reformed Church, for heaven’s sake?

“Everyone in cricket seems to have missed it. It’s amazing,” said Wisden editor Graeme Wright.

“It’s a bit weird, isn’t it?” said Andy Tong, of The Cricketer.

Even the near-infallible Association of Cricket Statisticians had failed to number Tom among those reluctantly given out.

More than seven years after the sad event, Wisden finally published a very good obituary. “His death was not widely noticed,” it said.

TOM Spencer stood in 17 tests, the first two 15 years apart. In 1971 he was umpiring at Edgbaston when Zaheer Abbas, the great Pakistani, hit 274 in only his second test.

“When he got 50 loads of people ran on, shoving money in my pocket for Zaheer,” Tom had recalled. “It happened every time he got another fifty.

Afterwards in the bar, Zaheer – “terrific gentleman, educated sort of chap” – asked Tom for some of the proceeds. The whole lot was still in the ump’s big white coat, locked in the dressing room.

“I had to lend him fifteen quid,” he said.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here