THE Beast from the East has caused the sands of time to shift on Redcar beach and create an unusual tourist attraction.

Hundreds of people visited the seaside to see the 6,000-year-old petrified forest and peatbed that have been revealed by the storm which has sucked out millions of tons of sand.

In truth, the trees are on show fairly frequently – the last time was 2013 – although this appears to be the most complete revelation for many decades. This time, even a shipwreck has been unsanded, although there have yet to be any human remains unearthed as happened on previous occasions.

To understand all this, we need to go back more than 10,000 years when the last Ice Age was coming to an end. Britain was not an island. It was connected to mainland Europe by Doggerland, a rich, wooded land of hills and valleys, populated with birds and animals, and peopled by thousands of hunter-gatherers who could walk, without getting their feet wet, from Redcar to Denmark.

As the glaciers began to melt so the sea levels began to rise, but what really did for Doggerland was the Storegga Slide. About 6,200BC (more than 8,000 years ago), there was an underwater landslip off the western coast of Norway. About 180 miles of coastal shelf crashed to the seabed setting up a megatsunami, a huge wave of water – perhaps the largest ever seen on the planet – which washed southwards down the east coast of Britain towards the English Channel.

It overwhelmed the forests of Doggerland.

Even when the waters subsided, Doggerland was left awash, its hills had become islands poking their heads up above the sea.

As the glaciers continued to melt, the waters continued to rise and gradually all of the islands submerged so that today they are just underwater sandbanks. The best known of them, of course, is Dogger Bank which is about 60 miles off Redcar. It is a good fishing ground and is named after Dutch single-masted fishing vessels, known as doggers, which caught cod there in the 17th Century.

The loss of Doggerland was obviously catastrophic for the humans of Doggerland. Hartlepool also has a petrified forest beneath its beach and when it was exposed in 1905 a human skeleton was discovered. Radiocarbon tests on the bones in 1984 suggested they came from about 3,700BC (about 6,000 years ago).

The smothering of the sand and the seawater blocks out the oxygen and so preserves the remains, be they tree or human. They tend, though, to go black which is typical of the anaerobic conditions in which they are sealed.

The tides of time have sucked out the sealing sand on countless occasions over the last 6,000 years, although it is only since the publication of newspapers – which like to tell their readers about local oddities – that we begin to see how frequently the forest reappears.

The first recorded sighting was by the Redcar and Saltburn-by-the-Sea Gazette in September 1871 which spoke of the “peaty deposits” beside the West Scar Rocks, which today lie in front of the vertical pier.

The Northern Echo of 1871 wasn’t interested in mere “peaty deposits”. It had a far more juicy story to tell.

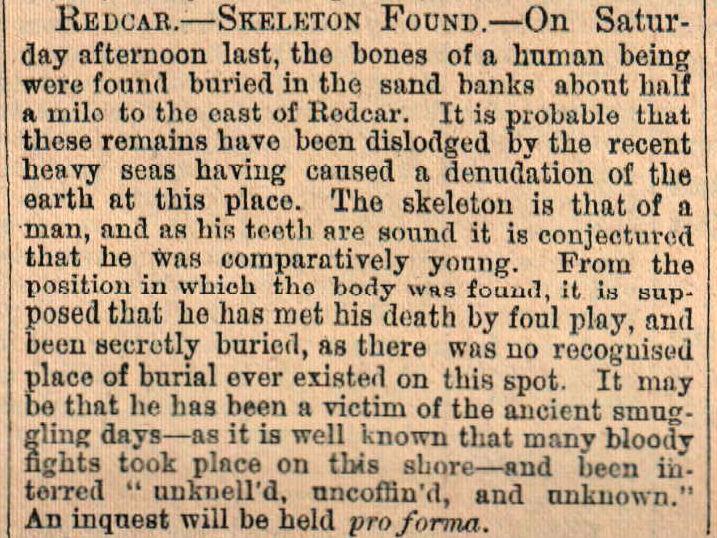

“On Saturday afternoon, the bones of a human being were found buried in the sand banks about half a mile to the east of Redcar,” it reported on October 2. “It is probable that these remains have been dislodged by the recent heavy seas having caused a denudation of the earth at this place.”

It was a male skeleton with sound teeth, so the Echo conjectured that “he was comparatively young”.

The conjecture continued: “It is supposed that he has met his death by foul play… It may be that he has been a victim of the ancient smuggling days, as it is well known that many bloody fights took place on this shore, and he had been interred “unknell’d, uncoffin’d and unknown”."

The inquest was held two days later at the Crown and Anchor Hotel, and the jury returned a verdict of “found dead”.

This was probably the most self-evident verdict in the history of verdicts, and so it was left to the Echo’s gossipy Whitby correspondent to fill in the gaps. “About 26 years ago a young man named Fishwick, a gamekeeper, in the service of Mr Vansittart, disappeared mysteriously from Redcar. It was at night when he was last seen. A search was made among the sandbanks for his body, but without success. He was a native of Yearby, near Kirkleatham.”

So much for the far more exciting theory about brawling smugglers and bloody fights.

The petrified forest re-emerged in 1883, and in 1902, when Henry Simpson of the Cleveland Naturalists Field Club wrote a detailed report of his sighting. He discovered “large portions of trees, chiefly oaks and firs, and they included trunks as well as branches, but seldom roots. Hazel nuts, acorns and decayed leaves were plentiful, apparently well preserved… antlers of the red deer and tusks of the wild boar were found”.

Mr Simpson also saw people carting off the peaty floor of the forest. They then dried it and put it on their fires where it blazed warmly.

Therefore, today's remains have been picked clean of the best bits over the centuries – skeletons, Neolithic stone tools, boar tusks, and free fuel for the fire – but there is still much of interest to see.

Attracting the most comments this week is the shipwreck near the rocks. It was last visible in 2013 when it was inspected by officers from Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council, which owns the beach.

Today, a handful of enormous container ships plies its trade serenely along the horizon and we forget how heavily sailed the east coast used to be: on one November day alone in 1807, 17 ships were wrecked on Coatham sands; on another February day in 1831, there were 12 wrecks and dozens of dead.

But the council officers were about to conclude that it was the uncovered wreck was that of either the Birger or the Mowbray.

The Birger was destroyed on Saltscar Rocks on October 18, 1898. She was carrying a cargo of salt from San Carlo on Spain’s sheltered shelter Mediterranean coasts to Abo, in her native Finland.

After five-and-a-half weeks at sea, the Birger was nearing the Norwegian coast when a hurricane blew her backwards over the Dogger Bank to Scarborough. Leaking and labouring, with her topsails in tatters and her masts broken, she was then driven north up the coast. Neither the lifeboats at Scarborough nor Robin Hood’s Bay could reach her; she was being flung so fast by the storm that the Whitby boat didn’t even have time to put to sea before she had disappeared.

At Saltburn, she was trapped among towering breakers beneath the brooding height of Huntcliff, but the turning tide through her back into the boiling sea which drove her up the sands until finally, at 2pm, she smashed through the matchstick legs of Coatham Pier and crashed onto Saltscar Rocks. Her mainmast snapped onto the deck, killing Captain KO Nordlink and his chief officer outright.

With immense bravery, Redcar’s two lifeboats tried to reach the stricken ship, and when they failed, people waded in. One chap had his leg broken when he was struck by wreckage, but they did haul out two sailors alive.

The other 13 drowned, and Coatham pier, which had opened in 1875, was also killed off and sold for scrap.

The wreck of the Mowbray, on December 9, 1834, was just as dramatic.

She was a brig from Sunderland which was driven ashore on the same rocks but this time the Zetland lifeboat managed to reach her and rescue ten crewmen.

As they came to the safety of the shore, the Zetland’s coxswain, George Robinson, saw that he had left behind two boys who had been lashed to the rigging to stop them from being washed overboard.

So, in a small boat, he set out again and, aided by the turning tide, he heroically brought them home, safe and sound.

Hopefully, the sands of time will be kind and leave the fossilised forest and the shivering timbers on view for a little while longer.

- The Birger’s anchor was discovered about a mile out to sea in 1999 and is now on display on the promenade. The Zetland is, of course, the world’s oldest lifeboat, and is the prize exhibit in the seafront museum which also contains the silver tankard that was presented to George Robinson in 1836 as a mark of appreciation for his bravery.

- With thanks to David Walsh and Chris Webber for their help with this article.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here