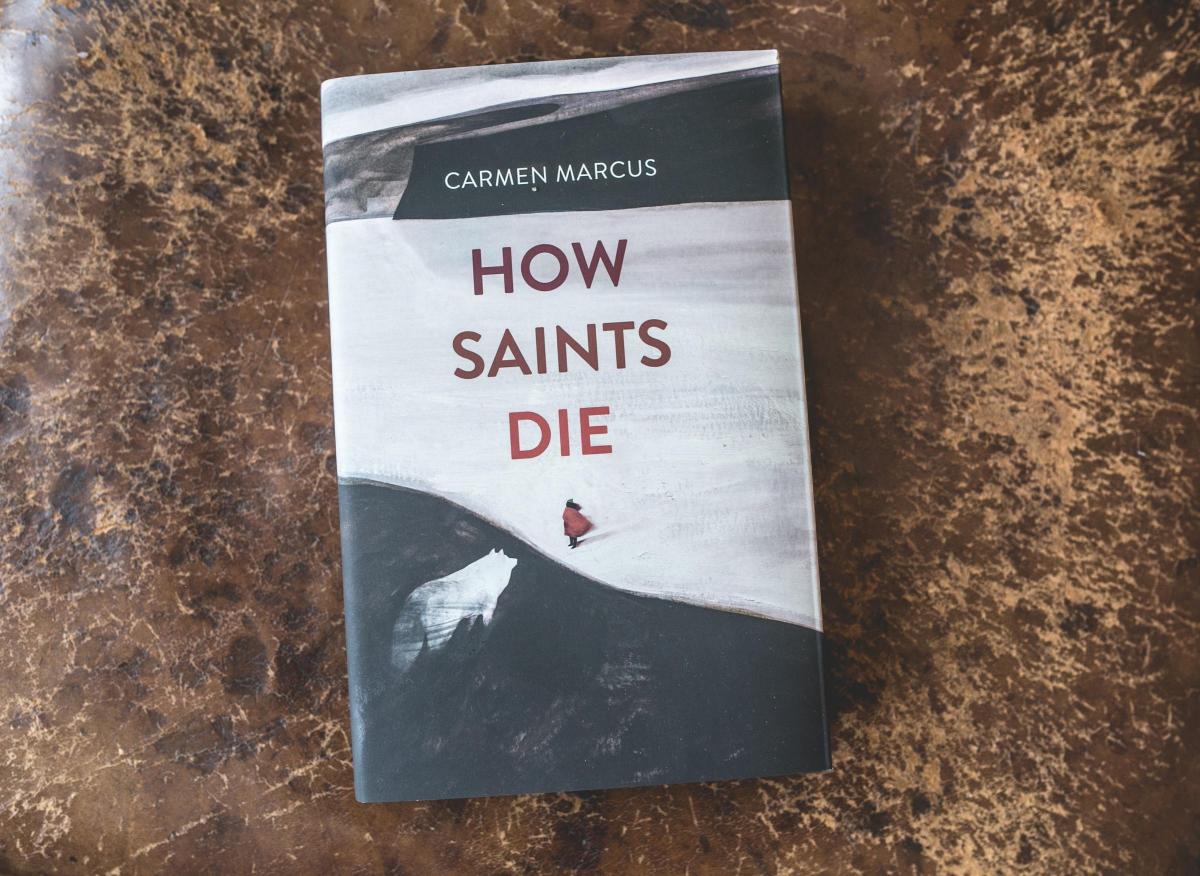

Award-winning poet Carmen Marcus has published her first novel, How Saints Die, a moving tale set on the brutal and beautiful North-East coastline where she grew up and still lives

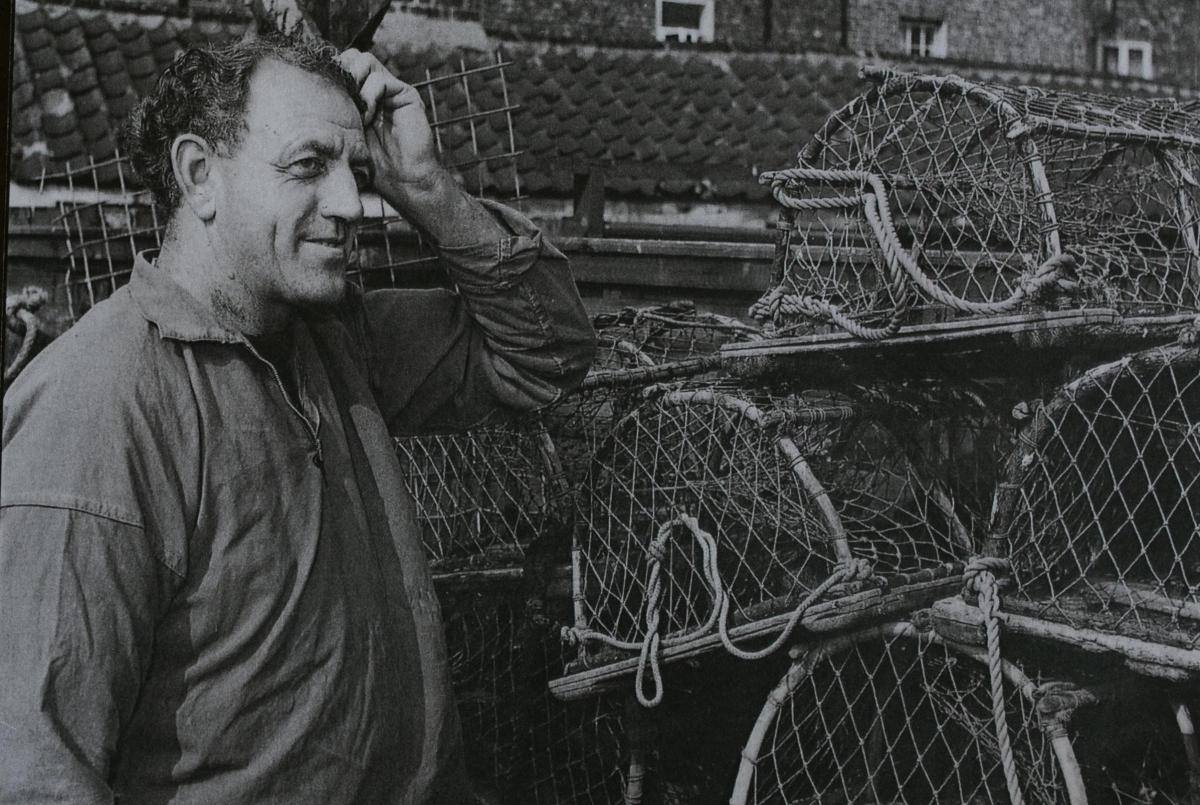

WRITER Carmen Marcus is bound to the sea. She grew up in Redcar in the 1980s in a tiny fisherman’s house with no central heating, car or phone. She and her fisherman father gathered sea coal from the beach for fuel, but also ate fresh lobster most days.

He came from a long family line of Yorkshire fishermen who had been living and working the coastline for 300 years, and her whole childhood was formed among their myths and rituals. She can still make a net with her own hands.

Carmen is a BBC Radio 3 New Voice and also won New Writing North’s ‘Northern Promise’ Award. She is much in demand as a performance poet and has appeared at the Royal Festival Hall. Before becoming a writer, Carmen was a teacher, then worked to bring theatre into classrooms. She volunteers to run creative writing workshops with young carers. Carmen was also a chocolatier, something she credits with teaching her to ‘finish things’ properly, something, she says, that is very difficult for would-be writers.

The title on your website is Carmen Marcus Fisherman’s Daughter. Is the sea integral to your work?

The sea isn't only a major subject for my work, but it reflects form and process too. I want to write about the light on the surface and the dark world beneath it.

I lived in Lancaster for a year. I felt as though I couldn't breathe even though it was so beautiful. I transferred to St Andrews. The School of English there, Castle House, overlooks the sea. Whilst waiting for my interview, I sneaked down to the beach and watched a curlew picking through the rocks. I knew I'd be happy there.

Living here, I can see daily the dramatic interplay between sky and sea. You can see a storm brewing out to sea, the shock of summer birds returning. I can find the secrets the sea hands over at the tide mark. There is no substitute for that kind of inspiration.

I compose and rehearse poetry to the sea, often performing at the end of the empty pier to the gulls.

Tell me about your family and home...

My father was born in 1920 and died in 1995. He was 56 when I was born. My mother is still thriving at 83. She came over from Donegal in the late 1950s and worked her way up to becoming a head chef. She's a great storyteller of dark ancestral tales. She says that she can taste love in food. I have a sister who lives by the sea.

Magnus was born in December. He's six months old and my first baby. My partner is a maths teacher, logical and pragmatic in ways that I love, but can’t comprehend. He supports me completely in my writing and keeps a watchful eye on random commas.

We live in a terraced Victorian flat with sea views in Saltburn-by-the-Sea. It's decorated to distract and inspire. In the living room there are antlers, a binnacle compass, a toboggan and a wooden leg.

The setting for How Saints Die is mostly Redcar with elements of Saltburn and a touch of wild Donegal where my mother comes from. It's very much a place from imagination, drawn from my father’s stories and my childhood. That Redcar doesn't exist anymore.

How do you feel about the demise of the fishing industry?

The problem I have with fishing is the “industry” part. My father was an inshore fisherman on a 32ft coble – not an industrial trawler. I have a beautiful letter my father wrote about fishing as a way of life. The lessons were to fish the seasons, respect the sea and not destroy habitats. He preferred using long lines as they don't tear up the fish. He hated nylon nets – I can't count the number of times we found seabirds entangled in them on our walks.

There is such a delicate relationship between fishermen and the sea. I think most of the superstitions exist to protect that balance. Humans have broken that compact with the sea, as fishermen and by using the ocean as a dumping ground. A farmer can restore the land to an organic state; we can't so easily undo what we have done to the sea.

Were you an unusual child?

As a child I lived in my head. It was hard being the only Carmen in Redcar, but I'm grateful now. Having an unusual name gave me permission to be weird. I was named after my father, Marcus Carman, the male version. I love that connection.

I felt the need to speak up, but it got me into trouble with students and teachers. In the1980s, you were schooled to know your place. Writing was a place where I could tell the truth quietly. The first poem I remember writing was about a fox being killed by a gamekeeper. I was nine. My teacher wrote “weird – minus one house point”. It was clearly too dark for primary school.

Describe your creative process...

I've written everywhere from boneshaking trains to park benches, but having a baby has changed how and when I write. I used to free-write by hand in beautiful notebooks for first drafts, but that requires two hands. Now I type with my thumb on my phone’s notes app. I haven't written anything long form in this way yet, just poems, non-fiction pieces and flash fiction. I write when my baby feeds and sleeps. The rest of the time I am fully his. He feeds through the night so I have these stolen hours in the early morning which are a new territory for me. I love the clarity of 4am thoughts.

Being a mother is a rupture in identity. It is a rebirth for the mother as well as a birth for the child; there is no bigger struggle with ego than to surrender to the raw need of your child. So yes – there is so much inspiration here as I am learning what kind of mother I'm becoming. It also changes your relationship with everyone around you. It is a fascinating and beautiful detonation in a family’s life.

What do you love most about the region?

I think that a wild animal doesn't know where its body ends and its territory begins as they are in constant conversation. That's how I feel about my home. How I move, think and feel is a reply to the ground beneath my feet.

People here are generous and supportive – if you ask for help, it's there. The people where I live have seen me struggle and grow as a writer. They’ve heard me reciting to myself on the pier; asked how it's going. They called me a writer before I could believe I was. “How's the writing going?” they would shout across the street against the wind. It's their achievement too.

I dare not say I'll never leave – fishing superstition – but I love it here and I want my son to grow up close to the sea. Maybe even take him sea-coaling.

- How Saints Die by Carmen Marcus (Harvill Secker, £14.99)

The Red Kite

This day, exactly a year ago we set off too late to Fountains. We didn't think we'd see anything.

It was so cold, there'd been snow, I ate all the chicken. That surprised him he was waiting to finish my lunch like he always did.

I was upset, not with him. I didn't even feel full.

It was the other women, the bright noise of their kids.

He said we were losing the sun but I set off up the hill.

There it was, the red kite, spiralling above us, a sort of god like the unknown red dot inside me, my son.

On being a chocolatier

I loved being a chocolatier, but it is not romantic work, it's brutal. When making an Easter egg you have to hold a mould filled with a litre of melted chocolate with one hand whilst bashing the mould with a rubber stick to get the bubbles out with the other hand; all to achieve that beautiful flawless finish. Chocolate is a diva of a material to work. To mould it has to be body temperature, 37°C; in summer it’s too hot to temper and in winter it gets shocked by the cold. What I enjoyed most was starting the day with nothing then finishing with 30 hand-made eggs and seeing people in the shop excited to buy them.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here