FIFTY years after his death it remains difficult to talk about the life of Tom Simpson without conversation turning to the day he died.

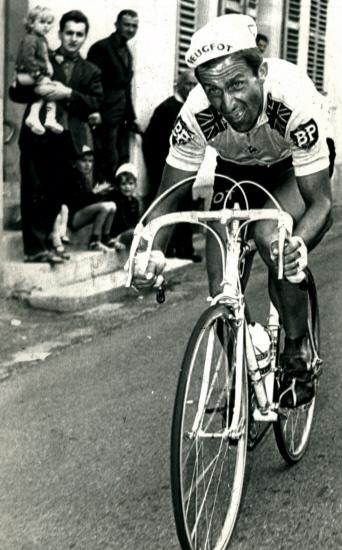

County Durham born Simpson was Britain's first cycling world champion, the first Briton to wear the yellow jersey in the Tour de France and remains the best Classics rider the nation has produced.

But talk to former team-mates, family members or his biographers, and the spectre of that fateful day on Mont Ventoux keeps returning.

It was on July 13, 1967, during stage 13 of the Tour, that Simpson collapsed less than a kilometre from the summit of Ventoux. Race doctors tried to resuscitate him to no avail. Simpson was dead at 29.

The official cause was "heart failure caused by exhaustion" but there were other factors. Race doctor Pierre Dumas said he found amphetamines in the back pocket of Simpson's jersey, while an autopsy said he had alcohol in his bloodstream.

Viewed through today's lens, it is easy to lump Simpson in with cycling's many pariahs, but it is a simplistic view.

Just two years after any form of doping controls were introduced, this was a time when the use of stimulants was still widespread. Many tested positive and were given a one-month ban before returning to race. For Simpson, being caught was the last thing he did.

"They talk about his death as though Tom was one in a couple of hundred who took anything," said his former team-mate Barry Hoban.

"You can't talk about Tom's death 50 years ago with the knowledge we have today because it's distorted."

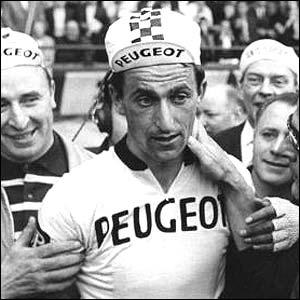

To understand Simpson, you must also understand him as a pioneer not only in cycling but in sport, an innovator and entertainer whose popularity in Britain exceeded that of his chosen profession.

"He'd been BBC Sports Personalty of the Year in 1965, he was the Bradley Wiggins of his time," said Jeremy Whittle, author of Ventoux: Suffering and Sacrifice on the Giant of Provence.

"He was suited, booted, sharp. He was on stage at the London Palladium. He liked cars, he liked champagne, he liked oysters. He was fully into the idea of being a rock star."

In an era before image rights, Simpson realised earning power was directly linked to public profile, and he played up to the cameras - adopting the 'Major Tom' persona of an Englishman abroad as he posed in a bowler hat with an umbrella and copy of the Times in hand.

Simpson raced fast and lived fast. The son of a Durham coal miner, raised in Nottinghamshire, had always been impatient. After winning Olympic bronze in the team pursuit in 1956 aged 19 he packed his bags for the continent and quickly made an impression on the road.

"He finished fourth in his first professional race and carried on succeeding like he didn't know how to fail," said his nephew, cycling journalist Chris Sidwells.

Simpson piled up an envious record in cycling's greatest one-day Classics - known as the Monuments. He would win three of them in his career - the Tour of Flanders, Milan-San Remo and the Giro di Lombardia, and recorded 11 top-10 finishes in his 15 Monument starts.

"When you tot up his wins in the Classics and then you tot up his top-10 placings, wow, that's one hell of a career," said Hoban.

The world title was his breakthrough moment at home. But for Simpson everything came back to the Tour de France. He was desperate to make money during a career he knew would be short, and to earn the serious sums he had to make it in the Tour.

His 1962 performance, when he wore yellow and finished sixth aged 24, suggested he could contend, but the Tour was not a race that truly suited Simpson.

"Basically, it was out of reach for Tom," said Brian Robinson, his former team-mate and flat-mate.

"Maybe he could finish second or third, but he lacked the stamina over three weeks."

He also lacked the discipline.

"The Tour was the race he wanted the most but suited him the least," said Andy McGrath, author of Tom Simpson: Bird On The Wire.

"He was too attacking, too nervy, too spasmodic. You could keep him cool for maybe 10 days and after that you didn't know what he would do."

Impulsiveness was a theme in many aspects of Simpson's life, but so was innovation. He was always pushing boundaries.

He was into marginal gains long before the phrase existed. He made his own saddle out of his wife's handbag, using a design which is now commonplace. He carefully managed his own diet, drinking gallons of carrot juice after learning of its health benefits.

He sought every advantage, every margin. It is soon easy to see the pathway to the tragedy on Ventoux.

"Tom would try anything to win," said Robinson. "It was so sad. He didn't need the drugs."

The 1967 Tour was no ordinary Tour for Simpson, who was negotiating a move to a new team and needed a good result to land the contract he wanted.

He piled pressure on himself, and things only got worse when he fell ill during the race.

The man who rode up Ventoux in stifling heat was a man already on the edge of exhaustion and dehydration, but a man who would never give up.

"He was a stubborn mule," Hoban added. "He went to his limit. But he wasn't someone who could step back and able to fully understand the long-term implications of what he was doing."

There may never be a consensus on what Simpson's true legacy should be, but when friends, family and well-wishers gather on Ventoux for a memorial on Thursday, they will do their best to separate his life from his death.

TIMELINE

1937 - Born November 30, in Haswell, Co. Durham

1956 - Wins bronze medal in the Olympic Games team pursuit in Melbourne, but blames himself for loss to Italy in semi-final.

1959 - April: Moves to France with a suitcase, two bikes and £100 in his pocket.

June: Signs his first professional contract with the Saint-Raphael-R.Geminiani-Dunlop team.

July: Wins stages four and five of his first professional race, the Tour de l'Ouest.

August: Finishes fourth in the world road race championships - the best British result to that point.

1960 - Made his Tour de France debut and narrowly missed wearing the yellow jersey, finishing 29th overall.

1961 - Wins Tour of Flanders

1962 - Moves into the yellow jersey in the Tour after finishing 18th on stage 12, having attacked on the Col du Tourmalet.

1963 - Wins the Bordeaux-Paris, a 557km race which started at 2am and used motorised pacing.

1964 - Beats Raymond Poulidor in a sprint finish to win Milan-San Remo.

1965 - September: Simpson beats Rudi Altig of Germany to win the world championships.

October: Won his third Monument race with victory in the Giro di Lombardia.

December: Won the Sportsman of the Year award and was named BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

1967 - March: Won Paris-Nice ahead of team-mate Eddy Merckx.

July: Simpson collapsed and died on Mont Ventoux during stage 13 of the Tour.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here