This year marks the 50th anniversary of a unique film and photography collective which documents the harsh realities of life in the North-East. Sarah Millington talks to one of its members

IT could be said that Amber saved the Quayside. It was the late 1970s, and the film and photography collective had just opened Side Gallery at its base at the Newcastle riverside site, then under threat of redevelopment. Desperate to safeguard it, founder members Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen and Graham Smith embarked on a photographic project faithfully documenting life there in all its richness and diversity. This led to an exhibition, a booklet and a film – and crucially, to Amber’s Murray Martin being given a useful government contact. He ended up forming a clandestine action committee – comprising himself and Newcastle Bookshop owner Brian Mills – and securing the listing of almost all the Quayside’s buildings.

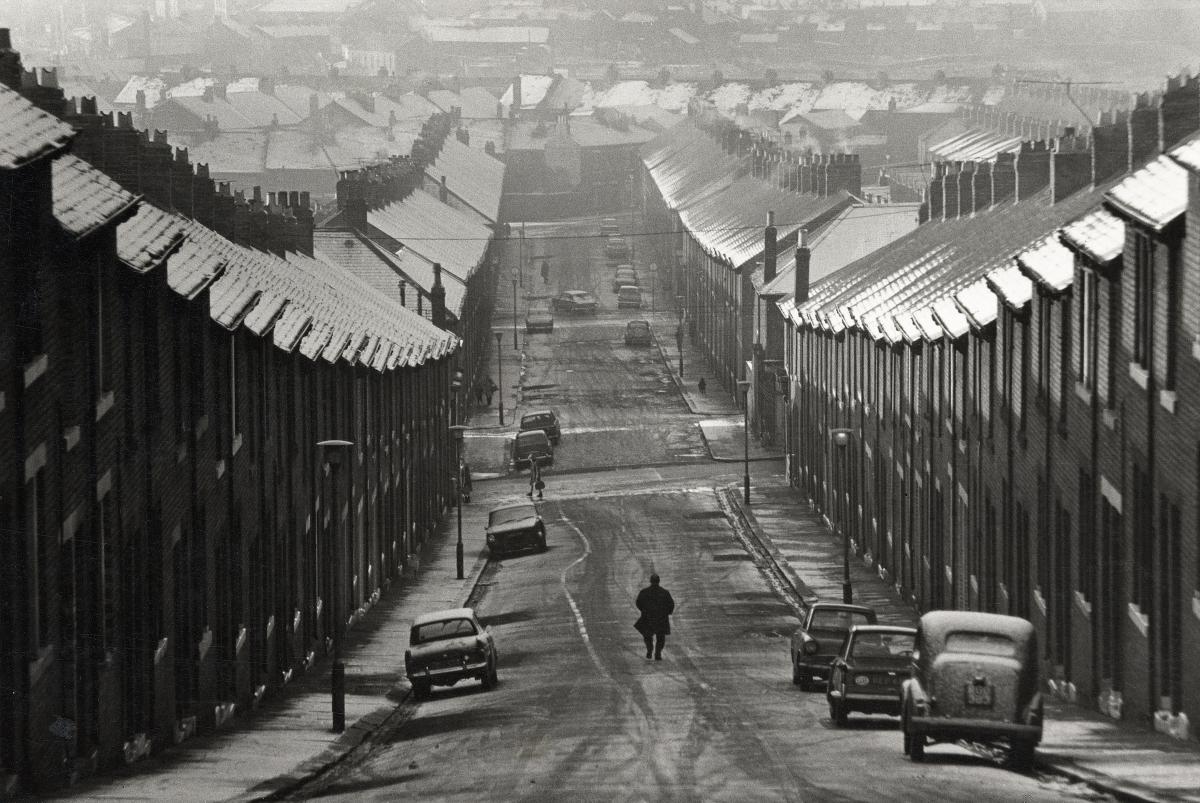

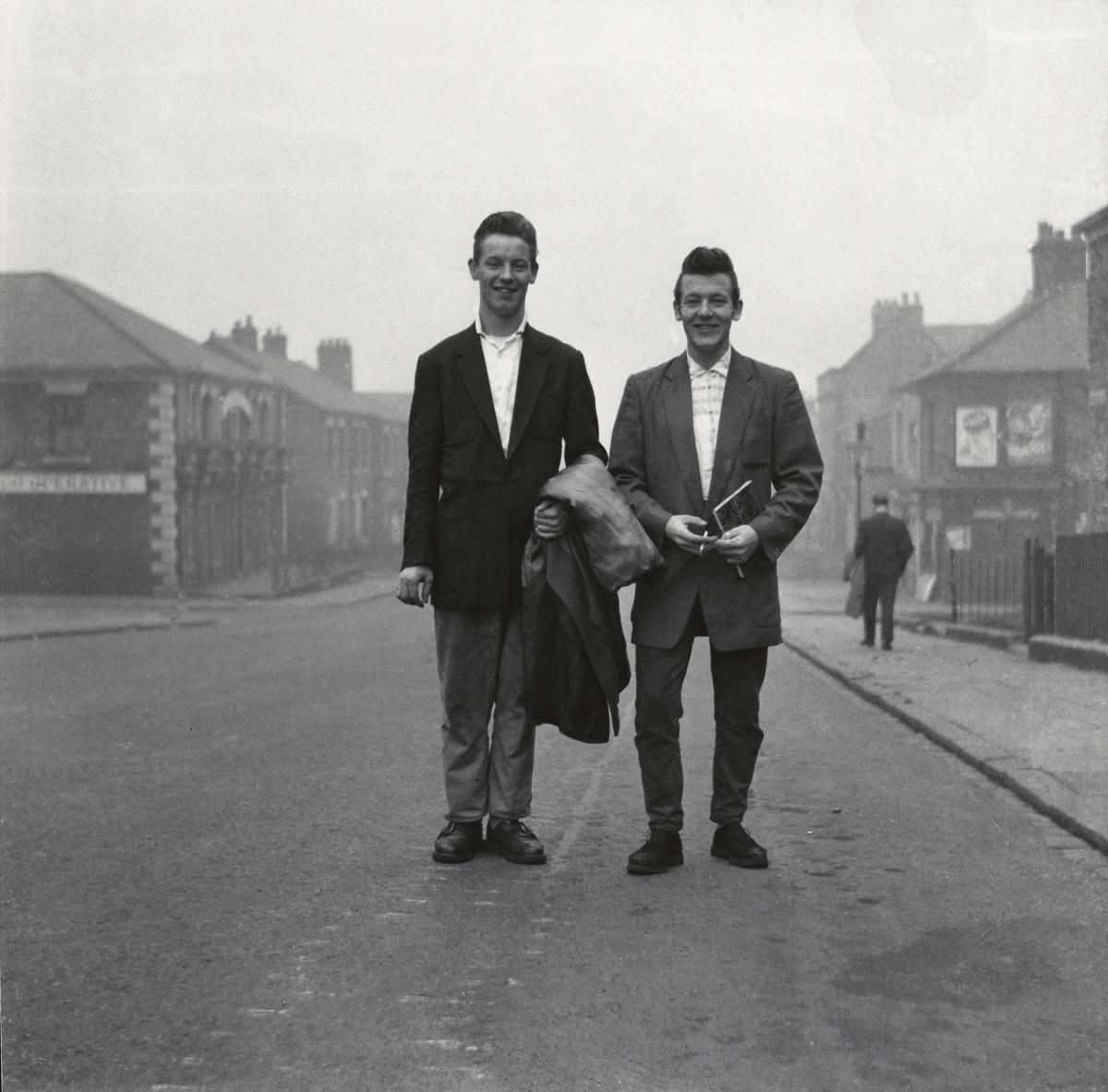

This act of preservation is a fitting testament to Amber’s ethos. Established 50 years ago, the group aims to document the lives and landscapes of working-class communities in the North-East. In the years since its inception, it has amassed a fascinating archive of film and photographic material – a real treasure trove of memories. Drawing heavily on the region’s industrial past, it has recorded everything from shipbuilding to steelmaking, faithfully preserving these now-defunct livelihoods for posterity.

While some of the collection is what you might expect – dour-looking individuals that fit the “grim up North” stereotype – there’s also fun and frivolity. The point, collective member Graeme Rigby explains, has always been to present life as it really is.

“What we’re concerned with is opening up on the voices from these communities and people being able to present their lives through our work,” he says. “It’s always complex and ambiguous. It’s not about making dogmatic work from an ideology – it’s about recognising and celebrating the complexity of what happens in these communities. Too often people reduce their stories.”

A sense of injustice at working class culture being misrepresented – or, worse, simply ignored – was what prompted a handful of students at London’s Regent Street Polytechnic to set up Amber in the first place. The year was 1968, and there was a feeling of estrangement among the group. “Murray Martin and other members of the collective were themselves from working class backgrounds, which they felt they were being pushed out of by education,” says Graeme. “They wanted to celebrate the kind of communities from which they themselves had come. The reason they moved to the North-East was because there was a sense of really strong working-class culture at the time, which there still is.”

Amber set up Side Gallery in 1977 because there was nowhere else that showed the kind of work it produced. At first niche and relatively unknown, in the 1980s it hit its stride. “It was very well funded through the 1980s,” explains Graeme. “But at the end of the decade, gallery funding got cut by 80 per cent. The gallery itself had a lower profile through the 1990s and it was really only from the end of the Nineties that we were able to rebuild it and it’s taken a long time.”

Fortunately, in recent years, the pendulum in contemporary visual arts has swung back towards documentary, and Amber has once again benefited from this. “From the early 2000s, the Heritage Lottery Fund was very keen to be able to support the collection and it was ultimately through it that in 2014, we redeveloped the gallery and the collection and we’ve been able to develop a whole strand of education work,” says Graeme.

This latest initiative, involving collective members going into primary schools, is a major part of the current agenda. Graeme says the response has been overwhelmingly positive. “The work has been great – really exciting,” he says. “A lot of the industry through which these communities defined themselves has often been erased. There are traces of it, but unless you know what you’re looking at, you don’t know what you’re looking at. I think children have been quite excited to see how rich the stories of their communities are.”

One of Amber’s key objectives is raising awareness of the importance of these stories – and encouraging people to take ownership of them. “A lot of what documentary is about is being able to see the stories in the community in which you live,” says Graeme. “There have, at different times, been people saying, ‘Why are you doing that? What are you still doing there?’ But what’s happening in these lives is really important.

“One of the interesting things now is high-resolution cameras and the ability to take really good photographs. It’s part of everybody’s everyday lives now. The idea of sharing those skills in the community is something that we’ve developed as a core strand of work. The process has evolved, but at the same time we’ve stayed committed to the same kind of communities we’ve always gone into.”

As far as the future is concerned, Graeme is clear about one thing – if Amber is to survive, production must continue. “People often don’t think that the present is worth documenting in the North-East,” he says. “They’re really glad that stuff was documented in the Seventies and Eighties but actually, the present is part of the process of extraordinary change and it’s really important that we continue to document that. It’s crucial that we are able to continue the narrative that we’ve been building over the last 50 years.”

Amber Film & Photography Collective, 5-9 Side, Newcastle, NE1 3JE

T: 0191-232 2000

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here