IN an interview with a national newspaper in 1992, Hannah Hauxwell was asked she would like to be remembered when she died.

“With affection,” she told the interviewer. “I hope I’ve been able to give a bit of pleasure or do a little kindness to people I’ve met.”

She certainly achieved that aim, judging by the scores of tributes which flooded in yesterday when news broke of her death at the age of 91.

Born in 1926, Hannah Bayles Tallentire Hauxwell lived at the isolated Low Birk Hatt Farm in Baldersdale, near Cotherstone for more than 60 years.

For most families in the dale it was a struggle to survive, especially through the harsh winters, and it was no different for the Hauxwells. Few households had electricity or water on tap and the hard toil of farm work was relentless.

When all her older relatives died, Hannah was left to manage the 78 acres alone, struggling on by herself in the bleak landscape and rundown farmhouse.

She made a meagre living from five cattle and the barren acres which she hired out for grazing in the summer.

In severe winters she had to tunnel through snow drifts to lead her cattle to drink or trudge for miles with a sack of coal on her back.

Sometimes she used a pick axe to get water from the frozen stream and when it dried up, in high summer, she would search far and wide to get enough for her needs.

Hannah’s groceries were delivered once a month to a farm a mile away, and the coalman came once a year. She had to trek to the nearest village to pick up calor-gas drums so she could cook.

She had fond memories of the isolated but closely-knit community struggling to survive in the beautiful but sometimes cruel dale – but also spoke sadly of how the community had changed as the 20th Century gathered pace.

“Most people have left now either died or moved away,” she said. “I’m afraid that’s the story of Baldersdale today – the place they abandoned, the dale they left to die. No chapel, no school, no recreation room, no pub, no social life of any kind really.

“The place was full once, alive with activity and children. Baldersdale is an empty place now and all that remains for me are memories, sweet memories.”

HANNAH’S solitary existence changed forever in 1973 when she attracted the attention of a film crew from Yorkshire Television.

The hardy silver-haired hermit, wrapped in a ragged army greatcoat and a tattered woollen scarf became an overnight celebrity when the documentary Too Long A Winter beamed her story into the homes of millions of people.

The film showed a lost way of life. Viewers were enchanted by her gentle, uncomplaining nature, and passion for her homestead.

Well-wishers started to regularly call at the farm to meet her, and Electricity Board workers donated enough money – and their time – to install mains electric at her lonely farmhouse.

Hannah was finally able to turn off her oil lamps in November 1974. “It’s going to be marvellous,” she told reporters.

Fans desperate to ease her burdens donated goods including a cooker, electric iron, television and washing machine. “I’m a bit wary of that,” she said. “It looks so complicated.”

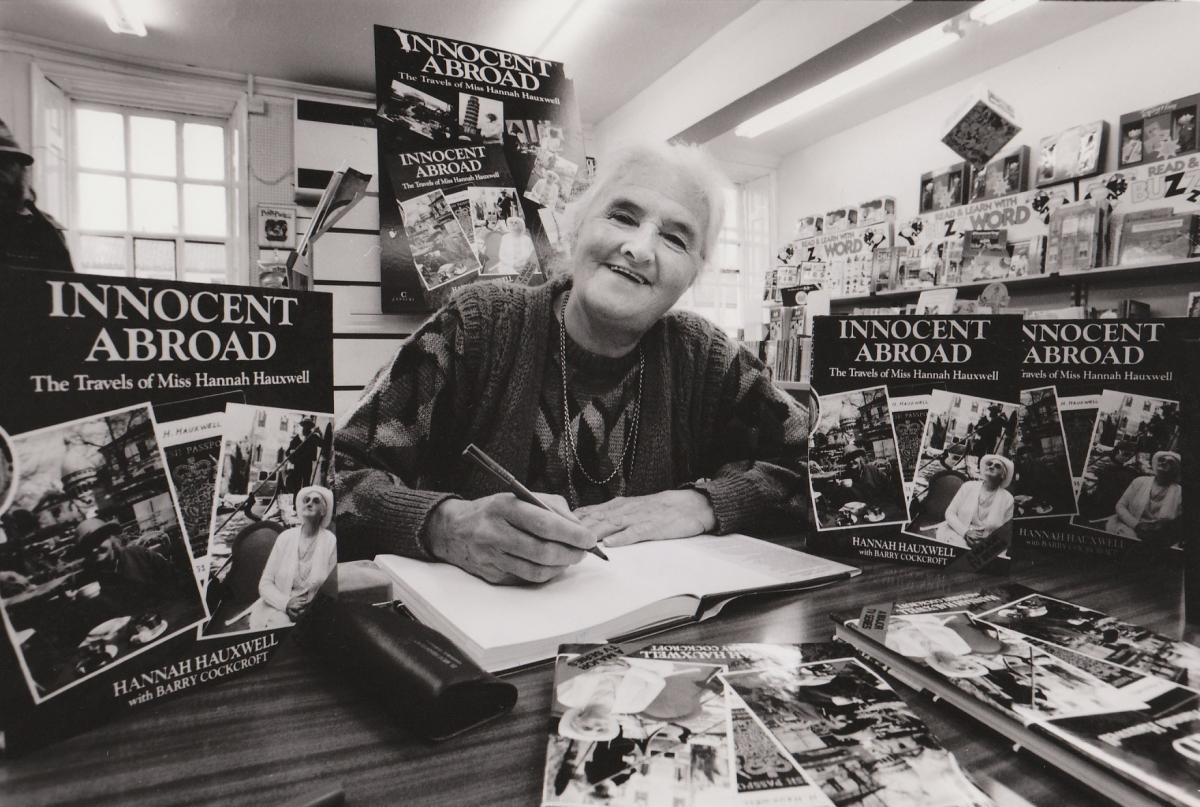

Hannah started to be inundated with offers for more publicity. Her first book Seasons Of My Life, a best-seller, was followed by Daughter of the Dales, with crowds flocking to signing events. More documentaries followed, including a series Innocent Abroad in which she travelled the world.

In 1980 she was invited a garden party at Buckingham Palace. Wearing a flowery brown nylon dress “bought at a Barnard Castle sale last week” and an ivory straw hat, she saw the Queen and Prince Philip at a distance and enjoyed the band playing Roses from the South – “a favourite of mine”.

In 1988, faced with deteriorating health, Hannah made the decision to put her farm on the market and move to a comfortable cottage in Cotherstone. “The winters are getting too much for me,” she said. “It’ll be nice to have a bath in a bath tub and not have to bother filling and heating cow pails.”

Her farm was split up – some was bought by private bidders, and 28 acres went to the Durham Wildlife Trust so rare upland meadows could be preserved.

Despite living out her latter years in relative comfort in Cotherstone – learning to cope with mod cons and life in a busy village – Hannah’s heart always remained at Low Birk Hatt.

“I know this place will always be loyal to me,” she said. “They cannot take it away from me. It’s mine and always will be even when I’m no longer here.

“In years to come, if you see a ghost walking there you can be sure it will be me.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here