THE Priestgate palace that is home to The Northern Echo is 100 years old today.

The landmark building was ceremonially opened on September 13, 1917, with plenty of speeches and a fine luncheon attended by the great and good of the area, who immediately moved on to an afternoon of more speeches and feasting as Darlington celebrated the 50th anniversary of the creation of its council.

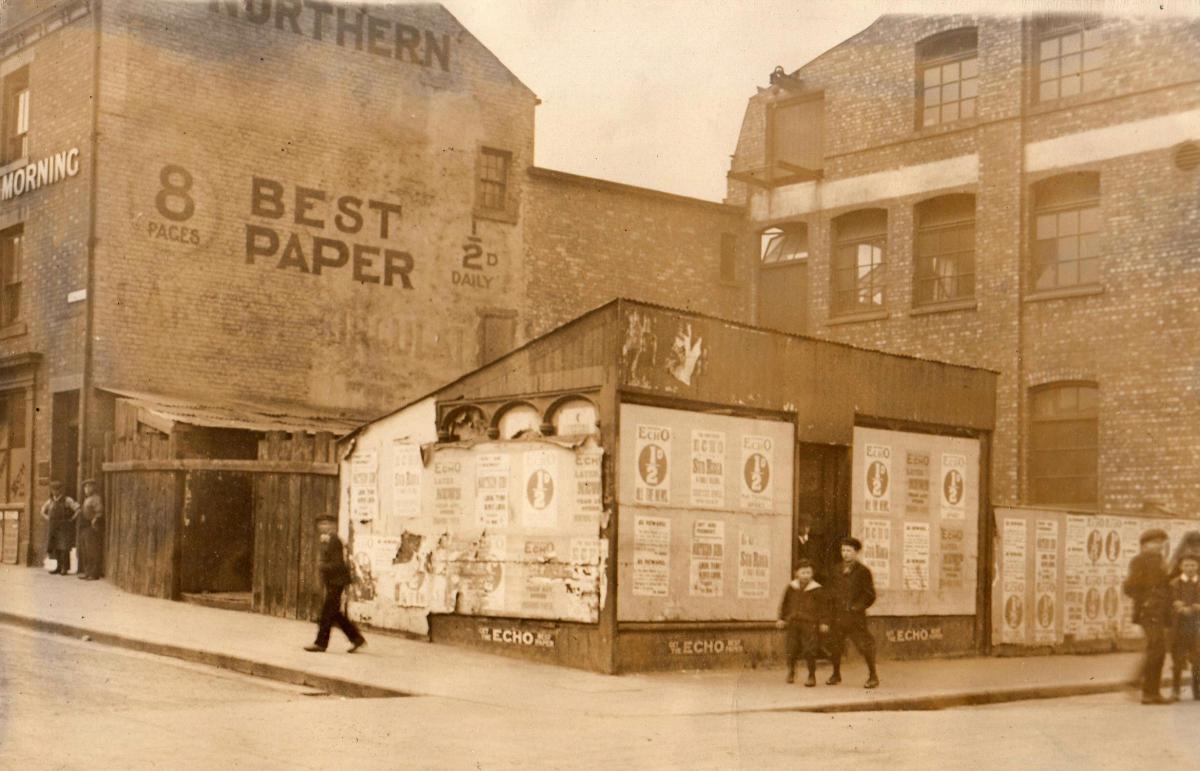

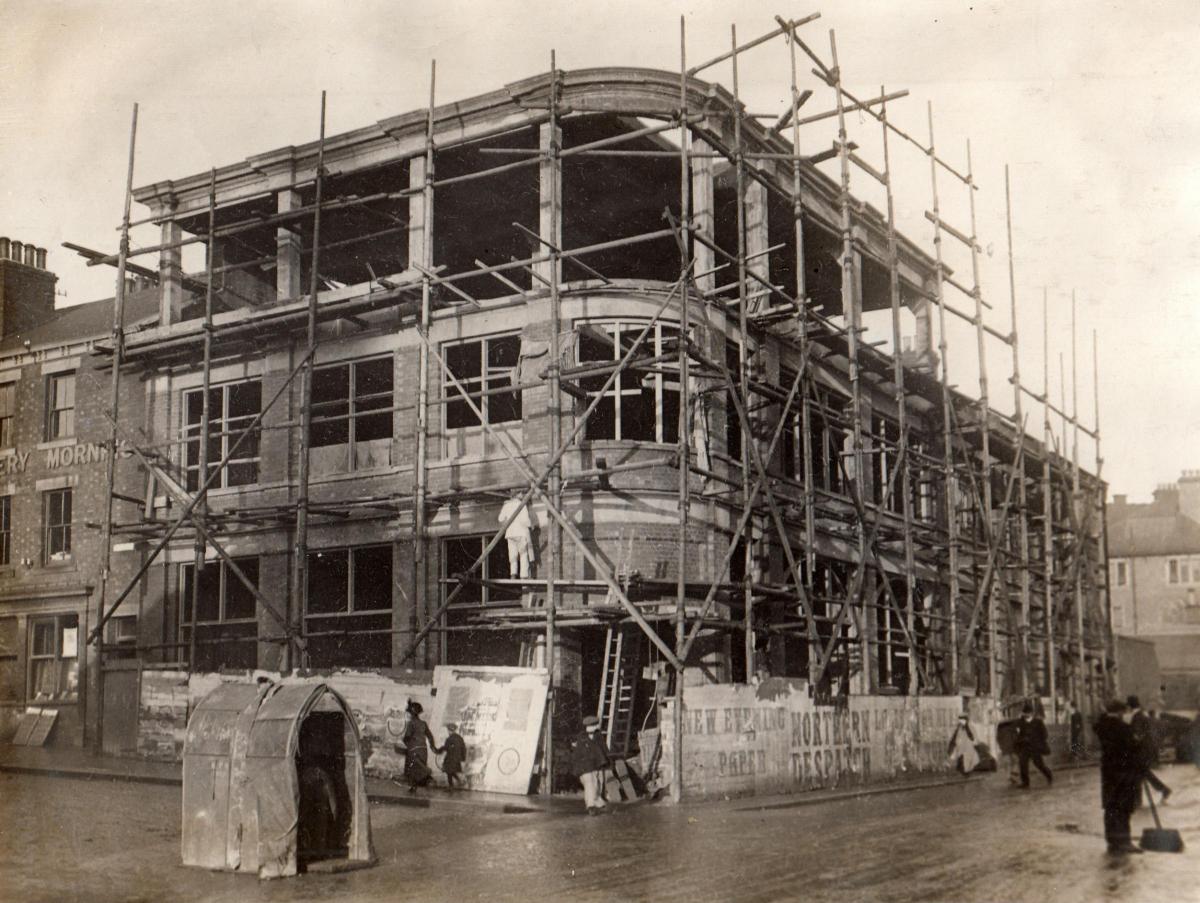

The paper had been based in a former thread and bootlace factory on Priestgate since it was first published on January 1, 1870. Before the outbreak of the First World War, with circulation and advertising revenue rising, it decided to expand around the corner into Crown Street with a £3,000 extension.

Construction commenced in 1914, but the start of the war put the project on hold. Work crawled along during 1915, stuttered in 1916, but the building was complete in time for the 1917 jubilee of the signing of Darlington’s Charter of Incorporation by Queen Victoria.

A silver key, “of chaste design” was presented to the guest of honour, Arnold Rowntree, the Liberal MP for York who was chairman of the Echo’s board of directors as well as heavily involved in his family’s chocolate business.

Watched by the paper’s 200 employees, he stepped through the corner door and declared the building open.

The paper’s managing director, Sir Charles Starmer, immediately drew his attention to a memorial in the entrance hall dedicated to the men serving in the war – 73 employees had joined up, of whom seven had paid the supreme sacrifice and ten were wounded.

The ceremonial party included the mayor of Darlington, Alderman JG Harbottle, the Cleveland MP Herbert Samuel who had recently been Home Secretary, and the newly-ennobled Lord Gainford of Headlam Hall. He was the grandson of Joseph Pease, whose statue stands on High Row, and in the 1920s would become the first chairman of the British Broadcasting Company.

Because of its disjointed beginnings, the Priestgate palace is a curious mix of pre-war ostentation and mid-war make-do. Few original features survive, but the corner entrance once had grand stained glass windows and a dark wood sweeping staircase.

However, it was proclaimed as the first building in Darlington to be made of “ferro-concrete” – concrete that was reinforced with metal.

After a brief tour, 80 guests left for a luncheon provided by Mrs Ballantyne in the King’s Head Hotel. The guest were amazed when before the starter arrived, a photographer took a group picture and dashed off to develop it. Before the dessert had been served, he returned with a souvenir print for everyone.

Mr Rowntree took up this theme of changing times in his post-luncheon speech. He said: “To show the great difference that railways and the Press have made to our life, one has only to mention the fact that 100 years ago, during the Napoleonic Wars, the news from Europe came by mail coach and was read aloud to the crowd in Darlington from the boulder stone. Contrast now the way in which we get news from the awful conflict which is raging in Europe today.”

What would he have made of the developments 100 years later where news of the latest awful conflict about to rage across the global is transmitted instantaneously in a tweet by the President of the United States?

After a further seven speeches and a series of toasts, proceedings were wound up by the editor, Luther Worstenholm, whose 20-year-old pilot son would be killed on the Somme 12 days later.

The Echo’s report concluded: “The guests then departed, most of them going to the celebration of the Municipal Jubilee in the Mechanics’ Hall.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel