In the first of a two-part series, Chris Lloyd tells the story of 'The Donald of Darlo' - the man who brought democracy to the town and tried to drain the swamp of the Peases

IT is 150 years ago this week that democracy came to Darlington, largely due to the efforts of a maverick megalomaniac businessman who had many Trump-like characteristics.

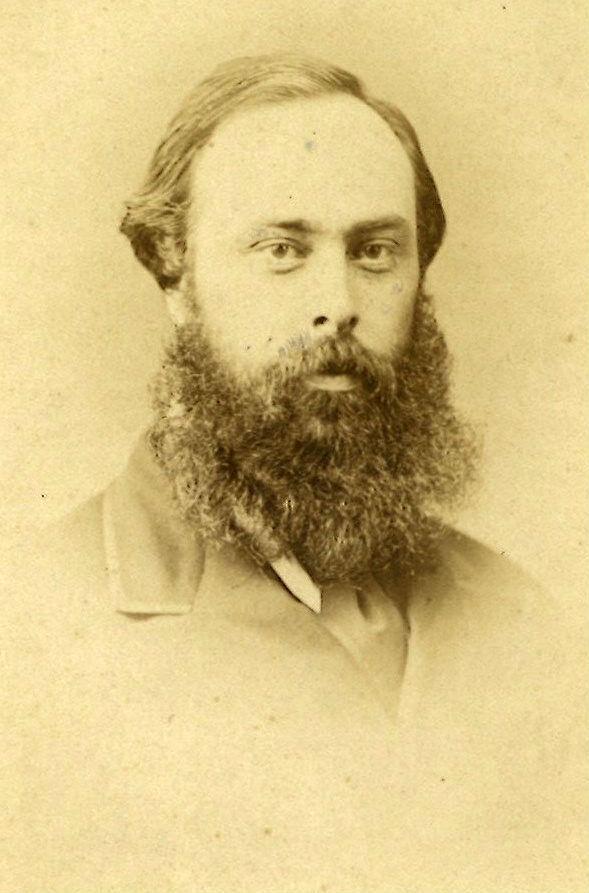

His name was Henry King Spark, and he led the challenge the town’s ruling Quaker elite. He promised freedom, he promised to drain the swamp of Peases, he alleged that his opponents used all sorts of underhand methods to defeat him and, through his newspapers, he railed against their fake news.

In fact, he could have been “the Donald of Darlo”.

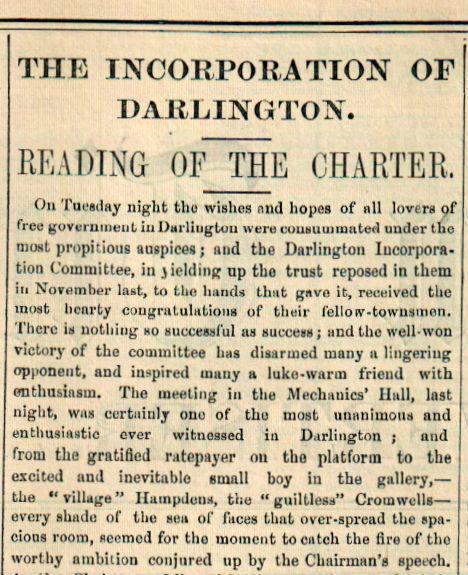

His first victory came on September 13, 1867, when Queen Victoria gave Royal Assent to Darlington’s new charter. This created the democratically-elected borough council which is commemorating its sesquicentennial during the Festival of Ingenuity later this month.

At the peak of his powers, he was received rapturously by his supporters wherever he went – if you believe everything that was written in his newspapers, the Darlington & Stockton Times (D&S Times) and the Darlington Mercury. As the prospect of power went to his head, just creating a council wasn’t enough for him. He wanted to become the town’s first mayor, and began campaigning under the modest slogan of “King Henry the Ninth”, and then he made an extraordinary, audacious attempt to topple the Peases’ candidate and become Darlington’s first MP.

This curious character was the son of a leadminer, born in Alston in 1825. He grew up in Leeds, where he showed such precociousness that he was evangelical preacher by the age of nine. He served an apprenticeship as a printer, and when Barnard Castle solicitor George Brown started the D&S Times in 1847, he got a job as a compositor – putting the hot metal pages together and proofreading.

In 1848, the D&S moved into Darlington, and Mr Spark came too. One day when he was putting together a page, a job advert for a “clerk and assistant traveller” to Mr Porter, a coal merchant based on High Row, caught his eye. He applied before the paper had gone to press, and got the post.

After a couple of years, Mr Porter mysteriously absconded. Mr Spark seized the opportunity, and took control of the business. With the gift of the gab, on one coal deal alone, buying low and selling high, he fluked £30,000 – nearly £4m in today’s money.

With the proceeds, he bought a collieries at Shincliffe and Houghall, near Durham City, and he opened up the Merrybent branchline, which ran to quarries near Scotch Corner. He promised the villagers of Barton that theirs would soon be a boomtown with a population of 6,000.

He bought a mansion, Greenbank, in Darlington and regularly threw his estate open to the working man. And in 1863, he bought the D&S and its midweek sister, the Mercury.

In political terms, he was a Liberal, like the Quakers of the Pease and Backhouse families, who dominated Darlington. Initially, he was part of the Liberal establishment, but they kept him at arm’s length, refusing to share their power.

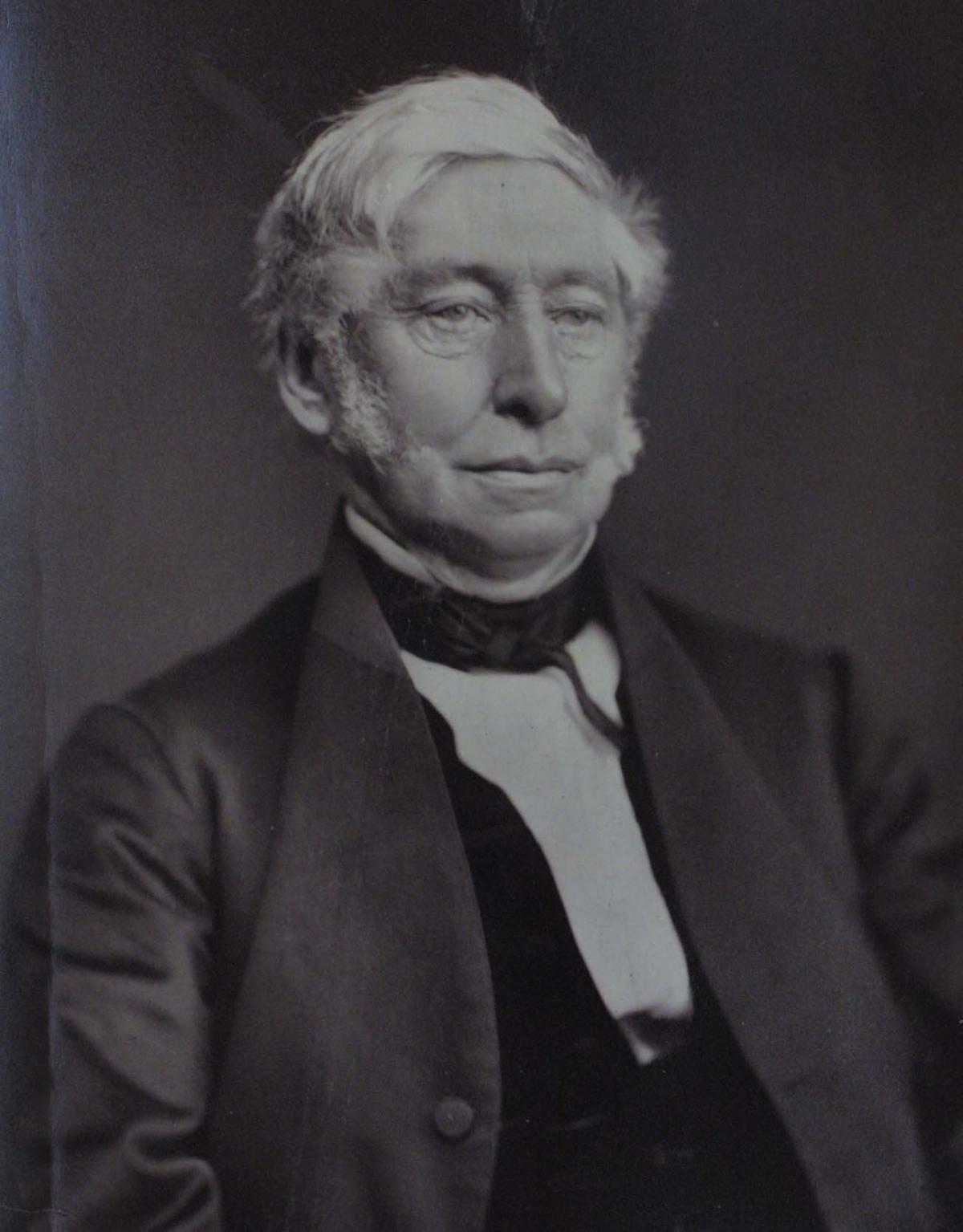

He also sensed that there was an undercurrent of unpopularity about the way this elite governed the town through the Local Board of Health. The “Pease Party” had 13 of the 16 seats on the board, and in the elections, votes were distributed according to the amount of property a person owned, so each Pease was able to vote up to seven times – for himself.

The Peases, in their defence, were presiding over the town at a time of unparalleled prosperity and a great rise in standards. But there was a feeling that they were used their power for their own benefit.

For example, in 1849, the family had formed the Darlington Gas and Water Company to pump unpolluted river water into the town centre from the Tees Cottage Pumping Station. John Pease was the company chairman, Henry Pease was the managing director, Joseph Pease the major shareholder, and the water had “the colour of India Pale Ale and a slight taste of pond”. It was, though, cleaner than the water in the town centre pumps which had been filtered through the graveyards.

In 1854, the Board of Health, chaired by Joseph and including John and Henry, agreed to buy the water company for £54,000 – twice what they had invested in it just five years earlier.

The Peases’ critics accused them of “unbridled profiteering”, and the Northern Daily Express said with incredulity: “The gentlemen who were acting for the ratepayers were precisely the same gentlemen who were bargaining for themselves.”

There was also a feeling that the Quakers were using their power to impose their puritanical values on the people. For example, they opposed theatres on moral and religious grounds, and so the Board of Health tried to prevent theatres from opening.

The Durham Chronicle said of Darlington on October 5, 1866: “The place is ruled with an iron hand by those who, on the hustings, spout and harangue Liberal principles to the multitude while at home they exercise a despotic sway by means of money, against which it is impossible to struggle.”

Because of this growing groundswell, the Peases granted a referendum in March 1866 on whether the Board of Health should be replaced by a more democratic council – it was rather like David Cameron’s granting of the Brexit referendum, in the misguided belief that he could control the result and the issue would go away.

In Darlington, the result was:

Yes: 562

No: 472

Abstentions: 388

Unreturned: 174

This enabled Joseph Pease to say that “a majority of the inhabitants have not expressed their opinion in favour of a Charter” and so he believed the issue had gone away.

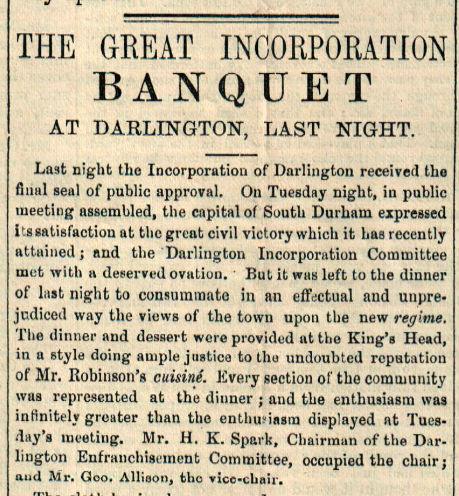

This was Henry King Spark’s moment. He seized control of the charter campaign, financing and chairing a committee that appealed directly to the Government and using the D&S to whip up a fury. The Government sent an inspector, Captain John Donnelly, to hold an inquiry in the Central Hall on March 25, 1867.

Mr Spark’s argument was that Darlington was no longer just a Durham backwater but a thriving, growing centre of trade that deserved its greater local control of its affairs like all the new industrial towns and cities were getting. The Peases could not disagree – after all, their power was based on the town’s increasing prosperity.

So disgruntled, they withdrew their opposition on the opening day of the inquiry, and Darlington’s name went forward to become a “municipal corporation”. The Queen granted Royal Assent to the new charter 150 years ago this week with the first elections to be held on December 3, 1867.

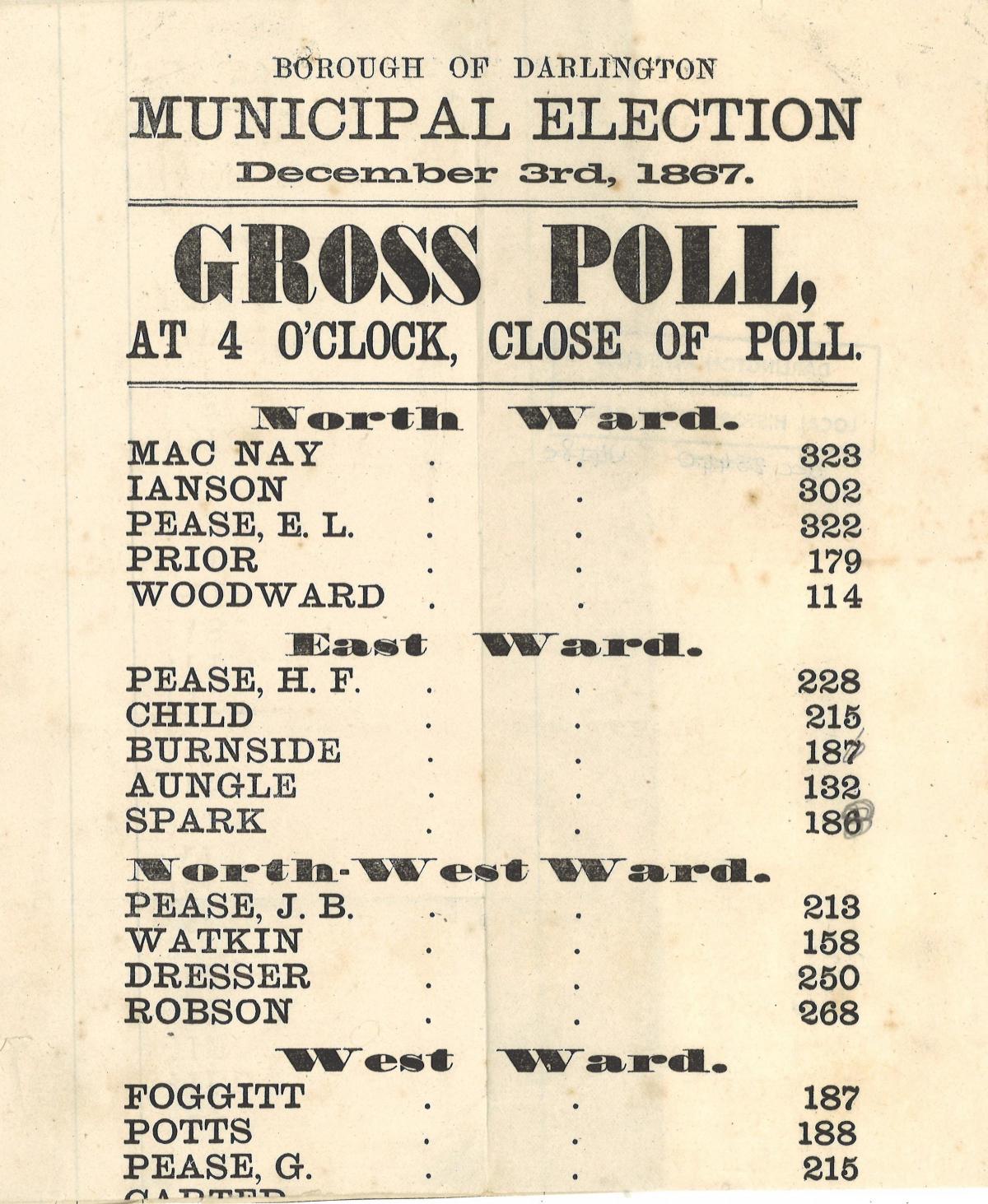

The charter divided the town into six wards which each returned three councillors. Mr Spark chose to stand in the working class East Ward, which pitched him against Henry Fell Pease, the son of Henry Pease.

“Here the admitted champions of the two principles at stake between the Corporation party and the Anti-Corporation party, were set against one another: Mr Spark representing freedom of election and self-government; Mr Fell Pease representing all the weight and influence of parties and persons, and all the narrowness and exclusiveness of self-contained and self-elected government,” said the Mercury.

Trumplike, Mr Spark called for the defeat of the “self-elected body or clique” of the Peases, accused his opponents of illegal tactics – Mr Fell Pease used “forcible, personal pressure” on voters – and announced that he wanted to become the town’s first first citizen using his modest slogan.

The election was very close. Not for Mr Fell Pease – he romped it, topping the poll with 228 votes. Mr Spark trailed in third with 188, elected to the council by just two votes.

But, according to Mr Spark’s newspapers, it was an enormous triumph and a grand endorsement of all he stood for. Thousands of ecstatic people followed him home: “Down from Bank Top, through the town, up Bondgate to Greenbank, the enthusiastic mass surged and sallied, shaking the clear winter air with their untiring cheers,” said the Mercury.

But the real result was that the first truly democratic Darlington Borough Council was made up of 18 men, 15 of whom were members of the Pease Party, including five who had the Pease surname. The swamp had not been drained at all.

The first council meeting was held on December 12, 1867, and one of its first duties was to elect the first mayor.

There were only two nominations: Joseph Pease and Mr Spark.

It wasn’t even a contest. Joseph Pease was unwell and not present, but still he won hands down.

In fact, he was so unwell, that he turned down the prestigious post and the council instead asked his younger brother, Henry, of Pierremont, who became Darlington’s first mayor.

Mr Spark didn’t even get a look in. Not a sniff.

The D&S railed furiously against the stitch-up. “What faith can Darlington have in rulers like these?” it screeched. “How can it trust its interest in the hands of men who have betrayed them?

“We believe that Darlington will answer these questions, sooner or later, in a tone that shall resound through the chamber of the town council.”

All Mr Spark’s Trumplike revolution had done was replace one Pease-dominated body with another Pease-dominated body which was headed by a Pease, but as the D&S editorial suggests, he was already planning an even more audacious bid to make Darlo great again: his eye was set on becoming the town’s first MP.

We’ll complete this story next week. To commemorate the 150th anniversary of Darlington council, Chris Lloyd is giving a free illustrated talk at 11am on Saturday, September 23 in Central Hall as part of the town’s Festival of Ingenuity. The talk is at the moment called “King Henry the Ninth and the Spark of Ingenuity”.

Henry King Spark was also vice-president of the Barnard Castle Mechanics Institute. Shortly before he died in 1899, he presented a large portrait of himself to the Institute which was hung in the Institute building – presumably Witham Hall. Does anyone know what became of that portrait?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here