AT five that mournful morning 20 years ago, the radio stirred me from my sleep by playing the National Anthem in my ear. Through a half-opened eye, I could see the sunrise painting the sky a vivid pinky-red.

Diana is dead, said the newsreader, and I bolted wide awake.

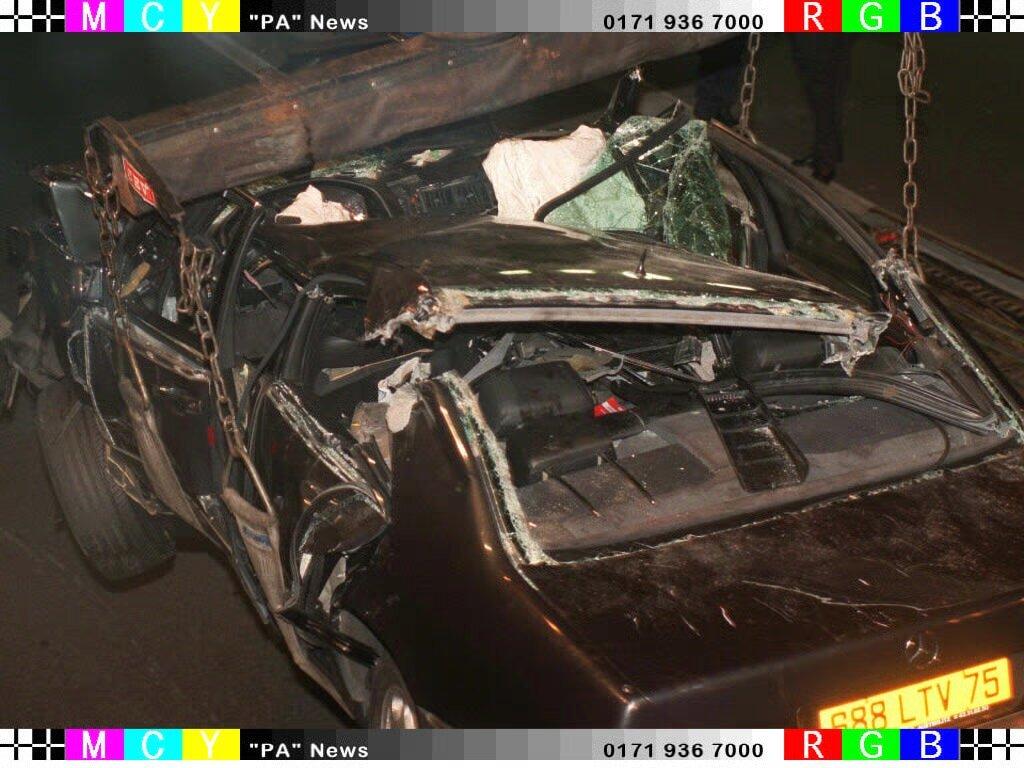

It was sobering, stunning news. Absolutely unbelievable. At 36, Diana was the world’s most famous, most beautiful, most photographed woman. To imagine her in such deathly disarray in the dark of a Parisian road tunnel was too painful, too tragic, to comprehend.

I walked to my local newsagents, in Hurworth Place. The sunrise had quickly gone out, extinguished by sullen grey clouds from which straight stair-rods of rain fell.

That Sunday morning’s fresh newspapers were on display but were already out of date. Such was the press’ fixation – and probably that of their readers – that all prominently featured Diana on her romantic break in Paris with her new lover, Dodi al-Fayed. The sensational tabloids had soaraway exclusives – “Sad Wills wants Di to ditch Dodi”, screamed one – while the serious broadsheets had acres of analysis: “Diana on the couch”, said the Sunday Times. The Mirror offered a 40-page glossy souvenir special entitled “Di and Dodi: A Story of Love.”

But it was, of course, a story that had already reached its unimaginably unhappy ending: their speeding car, driven by a drunk hotel security guard, had crashed at 70mph into the unforgiving concrete of a tunnel pillar.

People scurrying with their dogs through the rain spoke of how they were shocked and stunned by the utterly unexpected news, but one man in Darlington shot me an accusatory glance and, as if he had trodden in something unpleasant, said: “It’s one of them.” The paparazzi pursuing Diana for another photo for the papers were part of the cause of the fatal high speed chase.

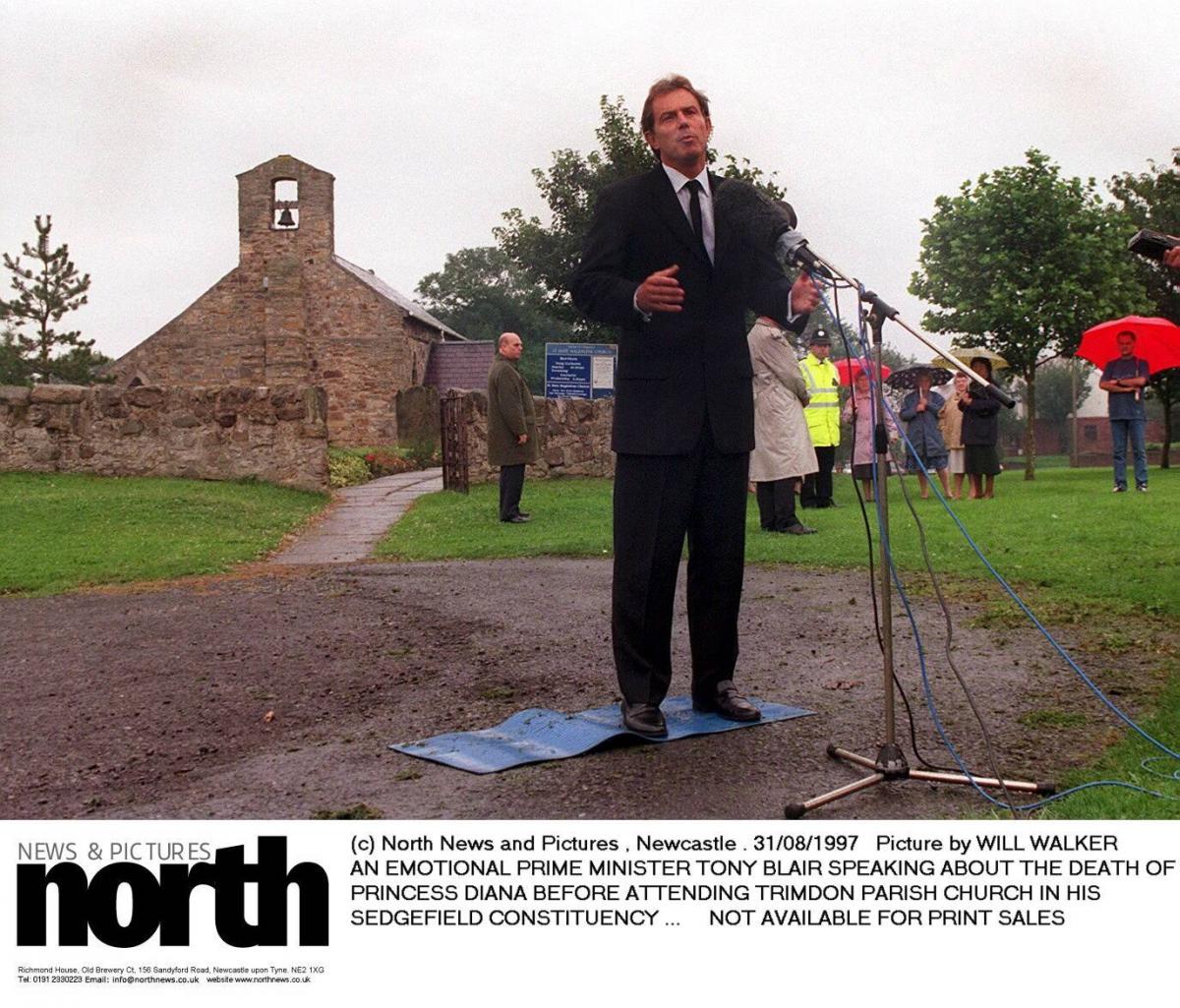

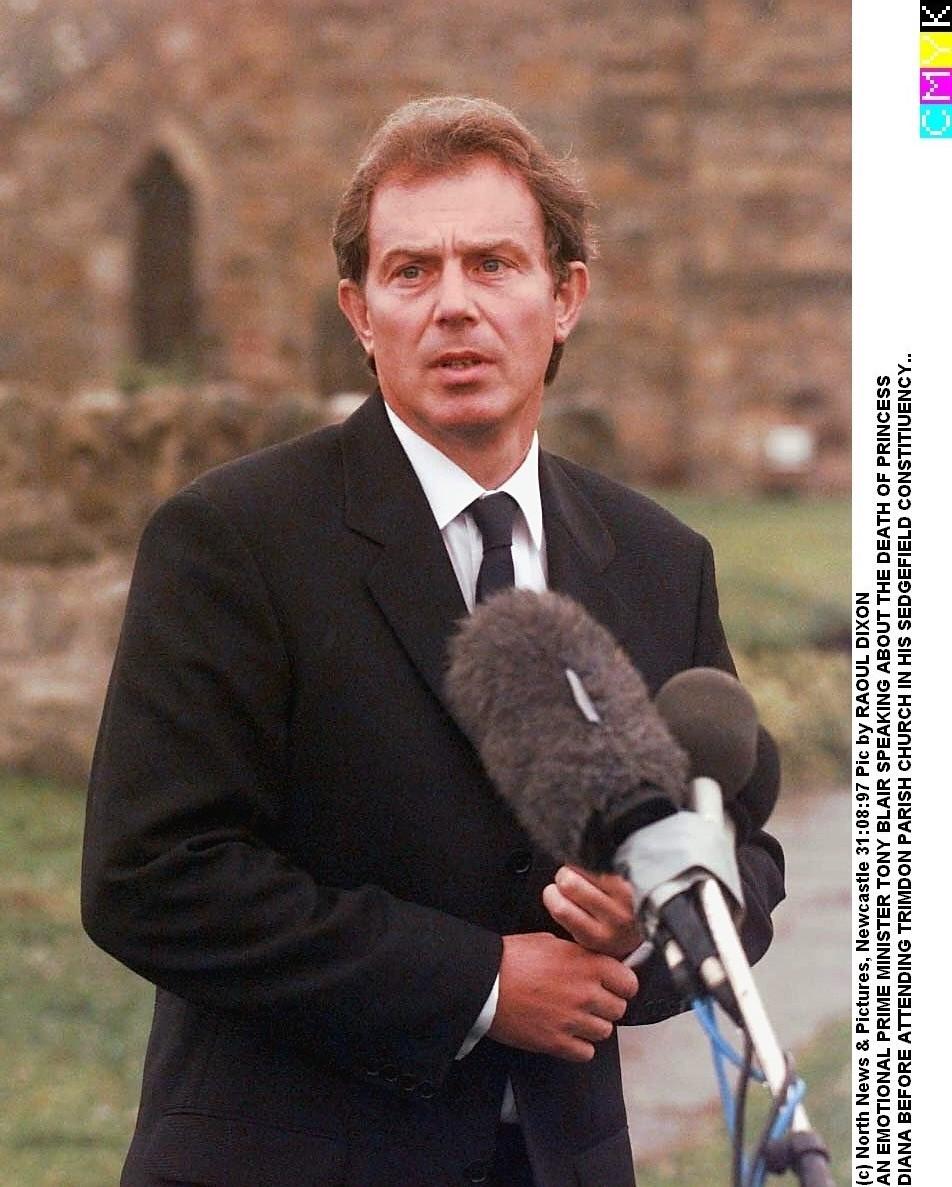

At 10am, I was on the green outside St Mary Magdalene Church in Trimdon Village, waiting for Prime Minister Tony Blair to attend the morning service where he was due to read the lesson – and make a statement.

A sombre knot of women, openly crying in the downpour, had gathered along with the pariahs of the world’s press. They set up their microphones and trampled the wedding confetti from the day before into the mud.

Mr Blair arrived at 10.30am, shielded from the rain by an umbrella held by his agent, John Burton. Mr Blair, 43, had been elected three months earlier after nearly 20 years of stuffy Conservative rule. Unblemished, fresh-faced and popular, he promised to lead the country into a new, modern dawn.

Diana was doing the same to the royal family. Bright and youthful, and even more popular, she offered to lead the old fuddy-duddies behind the throne in a new, modern direction.

There was an air of patriotic optimism about the nation. New Labour, New Britain, new monarchy and a new breed of celebs had come together to form “Cool Britannia” – we’d won the 1997 Eurovision Song Contest and one of the Spice Girls burst out of an extremely tight Union flag minidress.

All that colourful hope seemed to drain in the Trimdon rain as Mr Blair, in a black suit with a black tie, approached the microphones. Behind his holiday tan, he was clearly ashen-faced.

“Tony was genuinely shellshocked, terribly upset,” remembers Mr Burton. “He’d had lunch with Diana and her boys at Chequers only a few weeks earlier, and he and Alistair (Campbell, his press spokesman), were really taken by her.”

Mr Blair had been awoken at 2am by a policeman standing at the foot of his bed in Myrobella – his constituency home in Trimdon Colliery. From the shadows, the policeman told of the crash and the fears for Diana. At 4am, the Prime Minister learned that there was no hope.

“I sat in my study in Trimdon as the dawn light streamed through the windows, and thought about how she would have liked me to talk about her,” he recalled in his book, A Journey.

He took a phone call from the Queen, who he described as “philosophical, anxious for the boys, professional and practical”, scribbled some thoughts on the back of an envelope, and then was driven, with his family, to the church.

“It was odd, standing there in this little village in County Durham on the grass in front of an ancient small church, speaking words that I knew would be carried around the country and the world,” he wrote.

It was only 200 words, and there was an awkward moment as he started when his Adam’s apple rose uncontrollably and he had to swallow hard. Eloquently fighting back tears, and leaving long, emotional pauses between clauses, he came to an end with a line so famous that there is now a plaque on the green marking the spot where he delivered it: “She was the people's princess and that's how she will stay, how she will remain in our hearts and in our memories for ever.”

Then, there was a long, desolate linger for the camera before he turned for the shelter of Mr Burton’s umbrella and they disappeared into the church.

In his 2010 book, Mr Blair wrote: “The phrase ‘people’s princess’ now seems like something from another age. And corny. And over the top. And all the rest of it. But at the time it felt natural and I thought, particularly, that she would have approved. It was how she saw herself, and it was how she should be remembered.”

Whether Mr Blair was speaking naturally or as an actor, it was a bravura performance. In those two soundbitten minutes, he captured and articulated the mood of much of the nation: a mood of shock, of concern for her sons, of acknowledgement of her flaws, of the depth of her humanity and of her emotional connection with the people.

The old Queen was silent and locked up in her ancient towers. It was as if the new Prime Minister was giving the country permission to grieve in a different, modern way.

In the hours and days that followed, a kind of mass hysteria took hold. To some, all the hugging and weeping was alien; to others, there was such a need to openly express feelings that they flooded town centre monuments with seas of cellophane-wrapped flowers. All had handwritten messages dedicated to Diana – Darlington’s Market Cross, for example, was overwhelmed with floral tributes.

As I drove back to Darlington that Sunday lunchtime exactly 20 years ago, the day darkened prematurely and erupted into torrents of rain that roared in rivers down the A67 while thunder rolled with a frightening sorrow overhead. The feelings of the nation broke, too, as people mourned both the death of Diana and the loss of the hope and humanity that she offered.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here