A semi-derelict bank is soon to open as a gallery of mining art as the redevelopment of Bishop Auckland speeds up. Chris Lloyd talks to the collectors whose paintings will soon be hanging on the walls

THE builders have just left the Old Bank Chambers in the centre of Bishop Auckland. They’ve cleaned the stonework, opened up a lost spiral staircase and picked out a few surviving Victorian features in white gloss. Most importantly, they’ve worked on the walls, plastering them, papering them and finally painting them so that, big and blank, they now yearn to have pieces of art hung on them.

The downstairs walls are a nightsky blue that is so deep that as you move into the back rooms of the old bank they become quite claustrophobic, crowding in on you. But upstairs, with the light flooding in through the former boardroom windows, they are bright and airy and the rooms feel wide and open.

The bank is due to reopen at the end of October as a mining art gallery, housing the Gemini collection put together by Dr Bob McManners, a former GP in the town, and Gillian Wales, the former manager of the town hall. Downstairs on the deep nightsky blue walls they are going to hang the underground scenes of men working deep in the dark of the coalface; upstairs they are going to arrange paintings of the men’s life above ground, of their communities, their pubs, their wives, their pigeons and, of course, their gala.

The permanent gallery is going to root the Auckland Castle Trust, which is transforming the town centre with its visions of faith and exhibitions of Spanish religious paintings, firmly in the soil of County Durham, and it is going to right a wrong.

“It was a piece of our heritage that was being ignored,” says Dr McManners. “Everyone celebrates the power of coal in terms of its industrial value but people forget about its cultural power. It dictated everything from the design of the houses, the design of the streets, the design of the communities to the layout of the land, and yet its social significance has not been appreciated. In this area, which was once part of the largest coalfield in the country, there are no monuments or galleries or museums in the county dedicated to mining and only a couple of ornamental pitwheels remain.

“People know what the pits looked like, but these paintings are about coal’s emotive power, about what it felt like to live in the mining communities. You get the passion from the feelings of the artist.”

Both he and Mrs Wales come from mining stock. Gillian grew up in Wingate, listening to the stories of her grandfather, Ralph Lee, who was trapped underground in the 1906 disaster, caused by an explosion of firedamp, in which 26 men were killed.

“My grandfather died of injuries received at the Dean and Chapter in Ferryhill,” says Bob. “He received a serious head injury, went blind and was crossing the road in 1932 to go to a football match when he was knocked down by a car.

“I was brought up in Ferryhill, surrounded by coalmines – that was my world. I’ve always drawn and painted since I was four – my drawings were the pits, although not quite literally.”

Gillian’s interest in mining art was further aroused when she worked as a librarian at Woodhouse Close where she got to know Tom McGuinness, whose work is now at the centre of their collection. “He would come in, a quiet, little chap, and he borrowed a lot of books about art, but one day in 1976, he came in with a poster he wanted me to put up,” she says. “I thought it would be for a jumble sale or something like that but it was for an exhibition he was having in a gallery in London.”

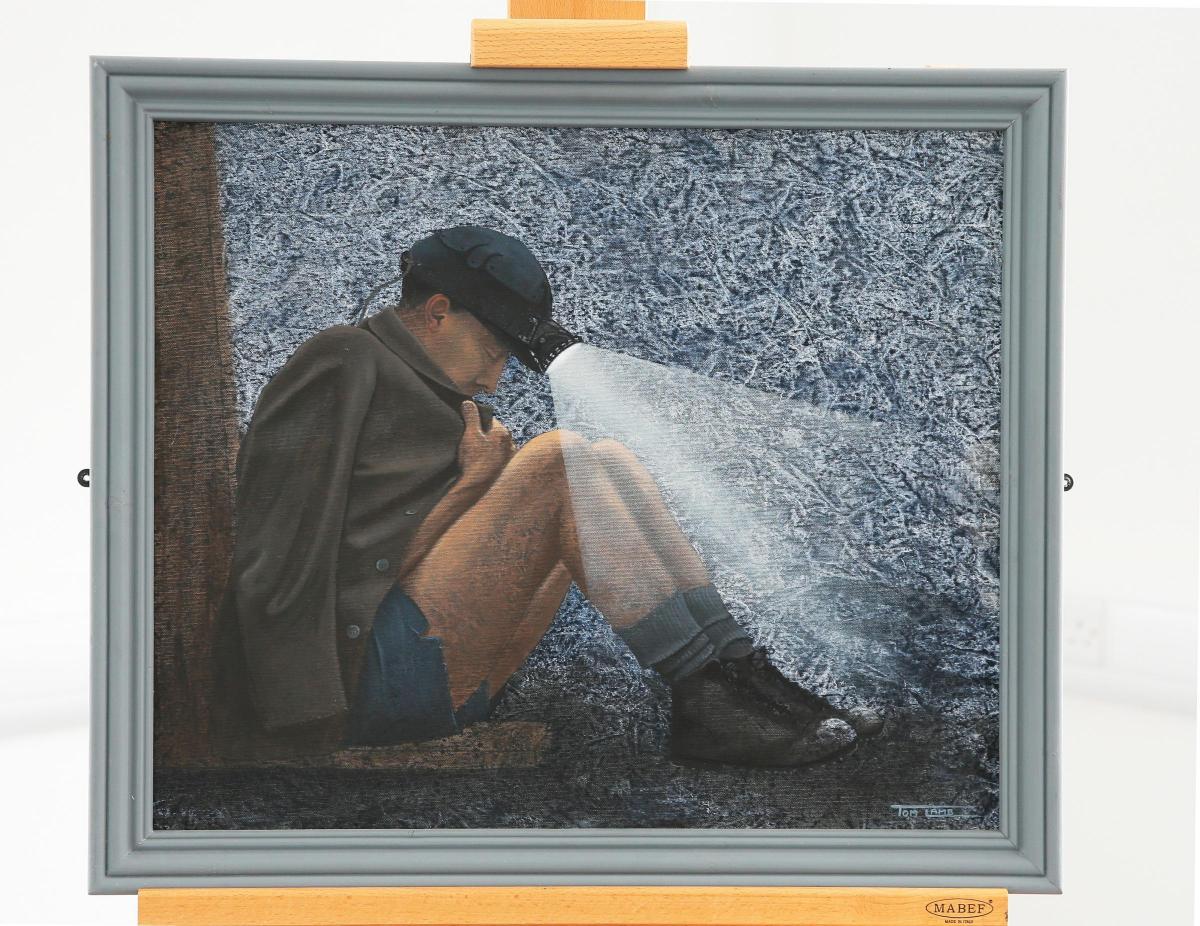

In the early 1990s, when Bishop Auckland Town Hall was restored, it hosted a major exhibition of McGuinness’ work. He’d been born in Witton Park in the year of the Great Strike, 1926, and his underground scenes are dark and gritty and claustrophobic, and you can feel his despair in them as the life of his industry – and so of his communities – was sucked out from the 1960s onwards. Bob and Gillian began researching his life, but realised they were only scratching the surface.

“We became aware how much mining art there was out there, not just Norman Cornish who was well known,” says Bob. “No one had researched it – so we did.”

Cornish, from Spennymoor, is the best known of Durham’s pitmen painters, although he came to specialise in life above ground, in the shapes of their communities dominated by chapel and pithead, in the smells wafting from their chip vans, in the way they lent bow-legged against a pub bar. “No one paints beer in a glass quite like Norman,” says Bob, and a large unseen Cornish, found rolled up in his house after he’d died in 2014, is going to be the star of the show on one of the big boardroom walls.

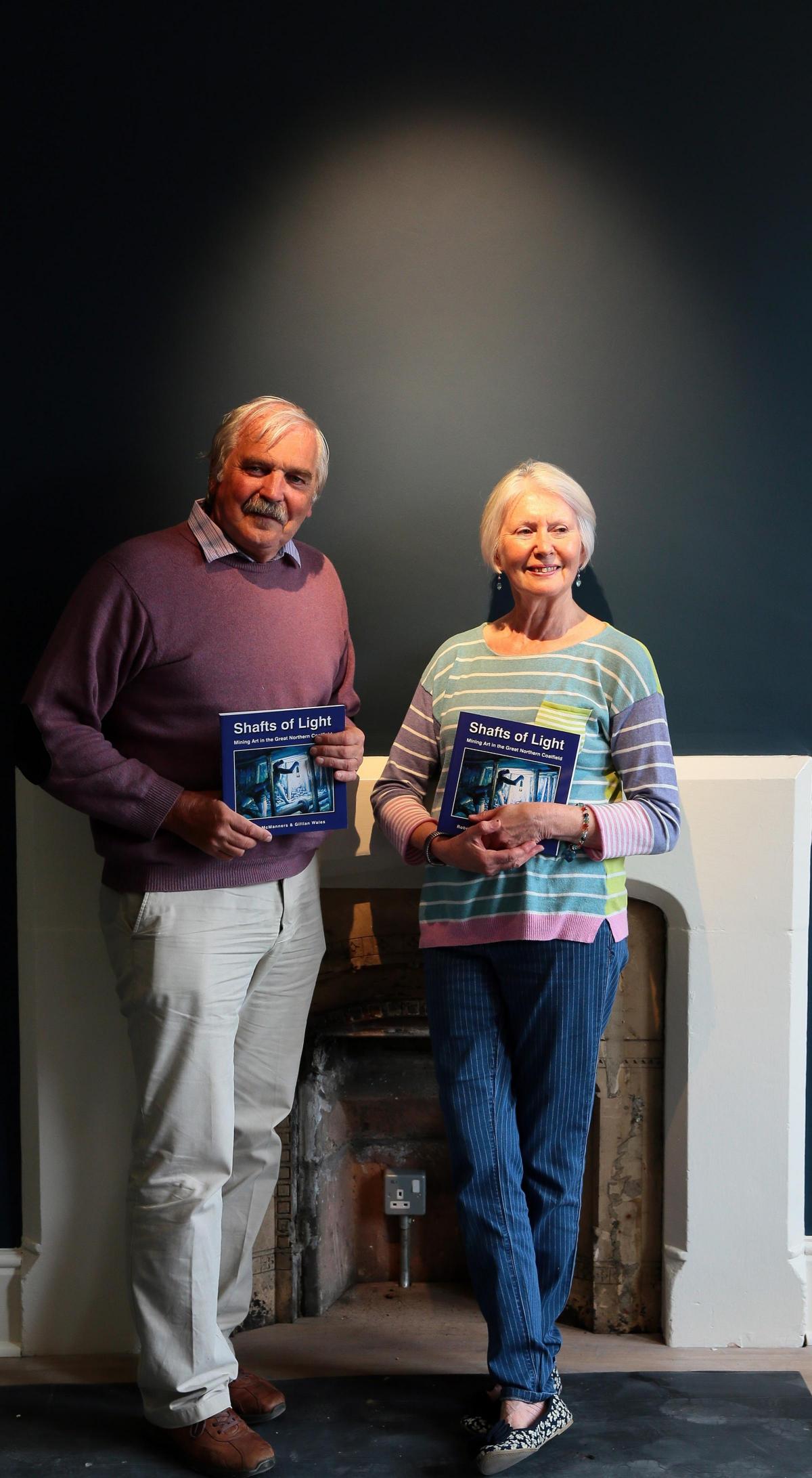

From their research into mining art came a book, Shafts of Light, and from the proceeds of the book came the collection.

“The first painting we bought was Tom McGuinness’ Durham Big Meeting at an auction in Newcastle in 1997,” says Bob. “It was huge, 7ft by 5ft. We got there just in time, I stuck our bat up with the number on it and got it, but we didn’t realise that we had to take the picture there and then.

“We’d gone up to Newcastle in my Austin Metro, so it must be the largest picture ever transported in such a small car, and Gillian had to lie on the backseat holding it. As we were going down the motorway, we thought we needed to celebrate and as the painting shows the County Hotel in Durham, we called in there. The concierge opened my door to let me out and said “is there anything else, sir”, and I said “yes, the lady in the back”, and these legs came out as she limbo’d from underneath the painting.”

Through purchases and gifts, the collection has grown so that now it contains 423 works by 42 artists – not all of them male. In retirement, and reaching a stage in life where one begins to ponder such things, they had been seeking a long-term home for the works. Now they are donating them to a trust which in turn is part of the Jonathan Ruffer-led Auckland Castle Trust, and in return the paintings will permanently be on display in the Market Place.

“It is bitter sweet as we’re giving our collection up, but it’s the achievement of an ambition we have had for 25 years and it is wonderful that it’s here in Bishop Auckland where we both live,” says Gillian.

The Old Bank has room for 80 or 90 exhibits, and there will be a temporary gallery to take in pictures from elsewhere to ensure a continuously fresh feel.

“We want the whole thing to be celebratory,” says Bob, who does most of the talking for the duo, although Gillian usually ends the sentences. “There’s an assumption that because these guys worked with their hands, they didn’t feel with their souls or appreciate the finer things in life. They were probably only formally educated to 11, or 14 after the First World War, so they only had a very shallow education. But they had every range of talent, ability, ambition and frustration. What they lacked was the opportunity and guidance and when it came, they blossomed.

“So this isn’t miners as victims.”

And Gillian completes the thought: “This is miners as heroes.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here