BOY soldiers as young as 13 were among dozens of Scottish prisoners dumped in a mass grave in the shadow of Durham Cathedral, experts believe.

Forensic analysis of skeletons uncovered during construction work on a new café, alongside detailed historical analysis of 17th Century documents, points to dysentery as the most likely cause of death.

Weakened by starvation and a forced 100-mile march from the battlefield, then crammed into their overcrowded cathedral prison, disease swept through their ranks and killed more than 1,000 in a month.

The bodies were then unceremoniously dumped at the bottom of Durham Castle’s walled gardens – and experts believe hundreds more are potentially buried beneath the buildings which fringe Palace Green.

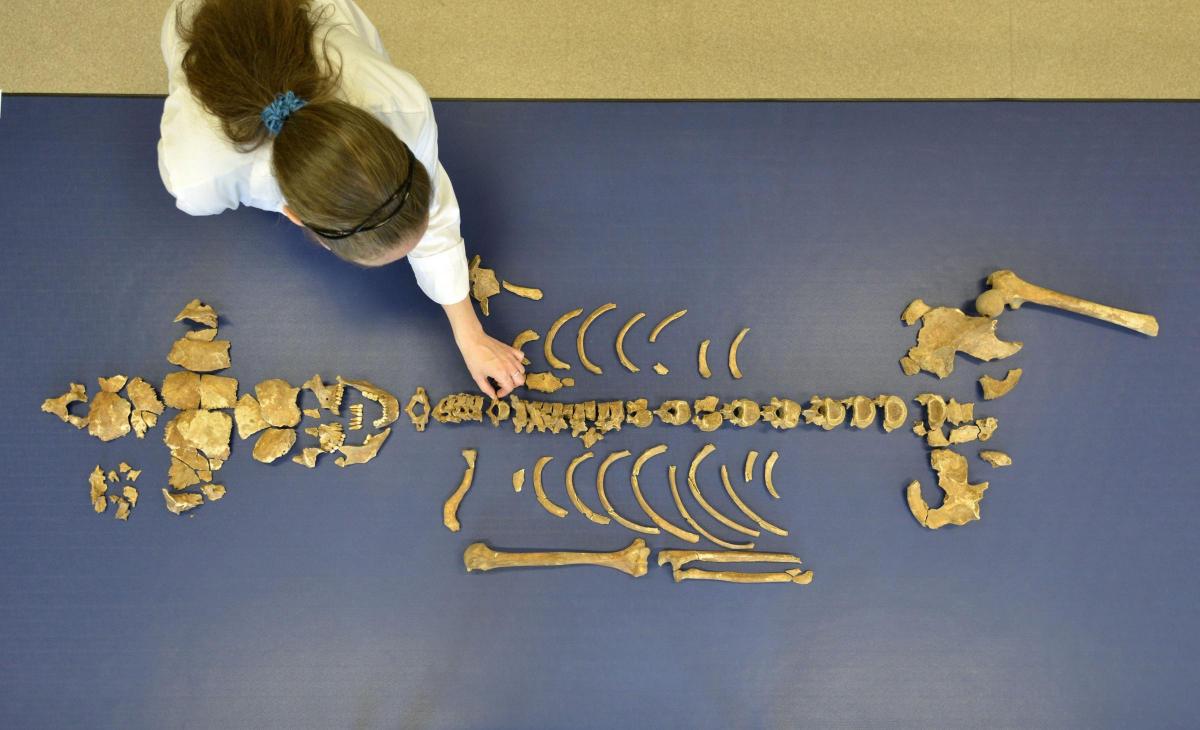

Anwen Caffell, from Durham University’s Department of Archaeology, analysed the skeletons which were found four years ago.

The remains of at least 17 individuals were found in the tangle of bones, although the exact number cannot be calculated, implying the bodies were dumped without ceremony.

She said: “They were in mass graves and were very tightly packed so the bones have become co-mingled and it has been very difficult to come up with a precise number of individuals.

“There does seem to be an element of disorder in the way they have been put in. It does imply a lack of care”.

Analysis shows that, along with a handful of mercenaries from the continent, most of the young soldiers were Scottish and came from poor backgrounds.

Speaking at the unveiling of a memorial plaque installed close to the spot where the bodies were found, Dr Caffell said: “The majority were in their late teens or early 20s, but there were some who were younger, perhaps 13 or 14.

“We don’t know whether the boys were fighting in the army or were some sort of camp followers or had another non-military role.

“There was evidence in the teeth that some of the individuals had suffered from deprivation in childhood.

The team found no evidence that any of the skeletons had met a violent end, but there were tell-tale signs in the bones that many had suffered some sort of infection shortly before they died.

Around 5,000 prisoners captured at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, were marched south to captivity. When they reached Morpeth, the starving Scots broke into a roadside garden to eat cabbages, complete with roots and soil fertilised with human waste.

Thousands died on the roadside and only 3,000 reached Durham in September 1650.

Dr Caffell said: “On the march down to Durham a lot of them fell sick with what was described as The Flux, which is probably dysentery.

“They were suffering from a contagious disease and were crowded, exhausted and underfed, into a small space where it spread”.

Professor Chris Gerrard, project leader, said: “They arrived here starving and ill.

“Both armies had dysentery before the battle. By the time they arrived here they would have gone 12 or 13 days without food”.

The sickest were taken to the castle, the rest into the cathedral, where the flagstones still bear scorch marks from their braziers as they tried to survive the first of two winters in prison, their living quarters at one end of the great church, their makeshift toilet at the other.

Gradually over the months the numbers were whittled down: the sick taken out through the Great Door to the castle to die; the strong sent out to work.

Among the survivors were a group of 150, put on the ship Unity bound for New England, where they worked for seven years before they were finally freed.

Prof Gerrard said: “They were clearly close to each other. You really get the impression that their sense of Scottish identity really bound them together throughout their lives.

“They all knew each other in Scotland, they fought alongside each other at Dunbar, they walked together in the march to Durham, they stayed together in the cathedral, they got on the Unity together and they stuck together in New England.

“They really were a band of brothers”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel