This Saturday, the 120th anniversary of a pit disaster which cost the lives of ten men will be remembered – as will the miraculous story of how one man survived

THERE was no hope. From the word go, the 11 men who had been trapped in East Hetton Colliery when water had rushed in like an immense tidal wave from an old working, filling the colliery completely, were doomed.

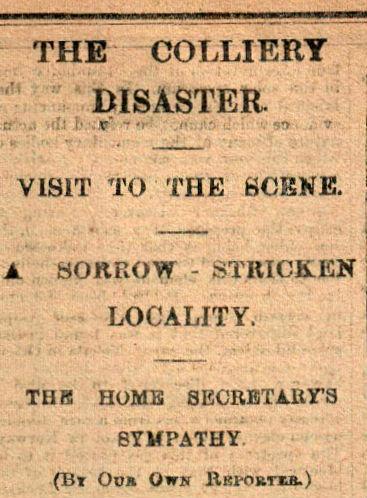

When the Echo’s reporter arrived at the scene of the latest coalfield catastrophe 120 years ago, he was struck by how quiet and calm it was. There were none, he wrote, “of those pitiful and heartrending sights which are usually witnessed on and around the pitstead after a catastrophe” because “the fate of the men is so undoubted that there is none of the anxious waiting at the pitmouth for news”.

The whole community, with its intimate knowledge of mining, knew the 11 men had drowned. In a stonefall, there was a hope against hope that a loved one had got lucky and was alive but trapped; in an inundation, there was no way out.

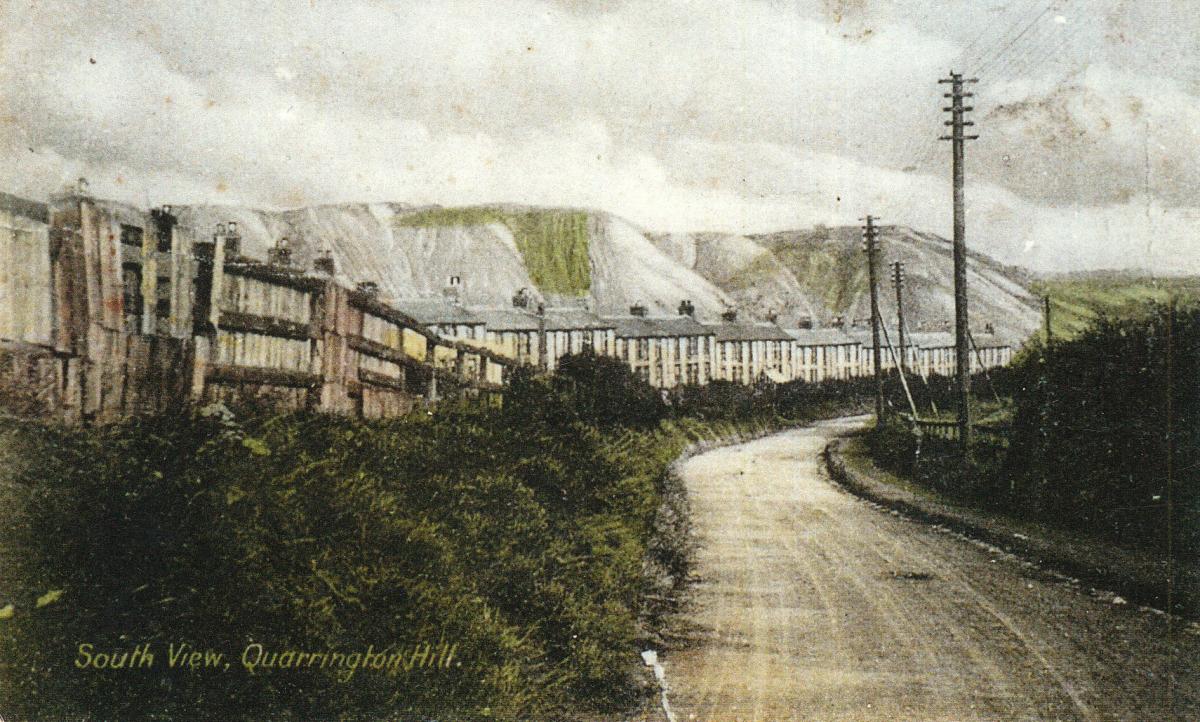

Victims of the East Hetton disaster of May 6, 1897

- John Garside, 53, of South View, Quarrington Hill

- Anthony Gibbon, 41, of Thornley

- William Hall, 50, of Kelloe

- Thomas Hutchinson, 49, of South View, Quarrington Hill

- James Oliver, 42, of West Cornforth

- Edward Pearson, 50, of Thornley

- John Raine, 63, of Kelloe

- Matthew Robinson, 27, of Thornley

- Thomas Roney, 58, of Ludworth

- Edward Smith, 26, of Thornley

So the 11 widows of East Hetton had been informed, the coffins were being made, and the insurance had already paid out.

In fact, 48 hours of the disaster, the Echo was appealing for the estranged wife of William Hall, described as “one of the drowned”, to come forward. Mr and Mrs Hall had lived apart for five years, Mrs Hall keeping the kids in the Crook district while Mr Hall, 50, had moved to east Durham. But, promised the Echo, “a considerable sum of money will be due to the family under the rules governing the Miners’ Permanent Relief Fund”.

The Echo concluded its report: “A pitiful circumstance is the fact that the wife of one of the drowned men, the deputy Wilson, was confined immediately after the news of the disaster became known.”

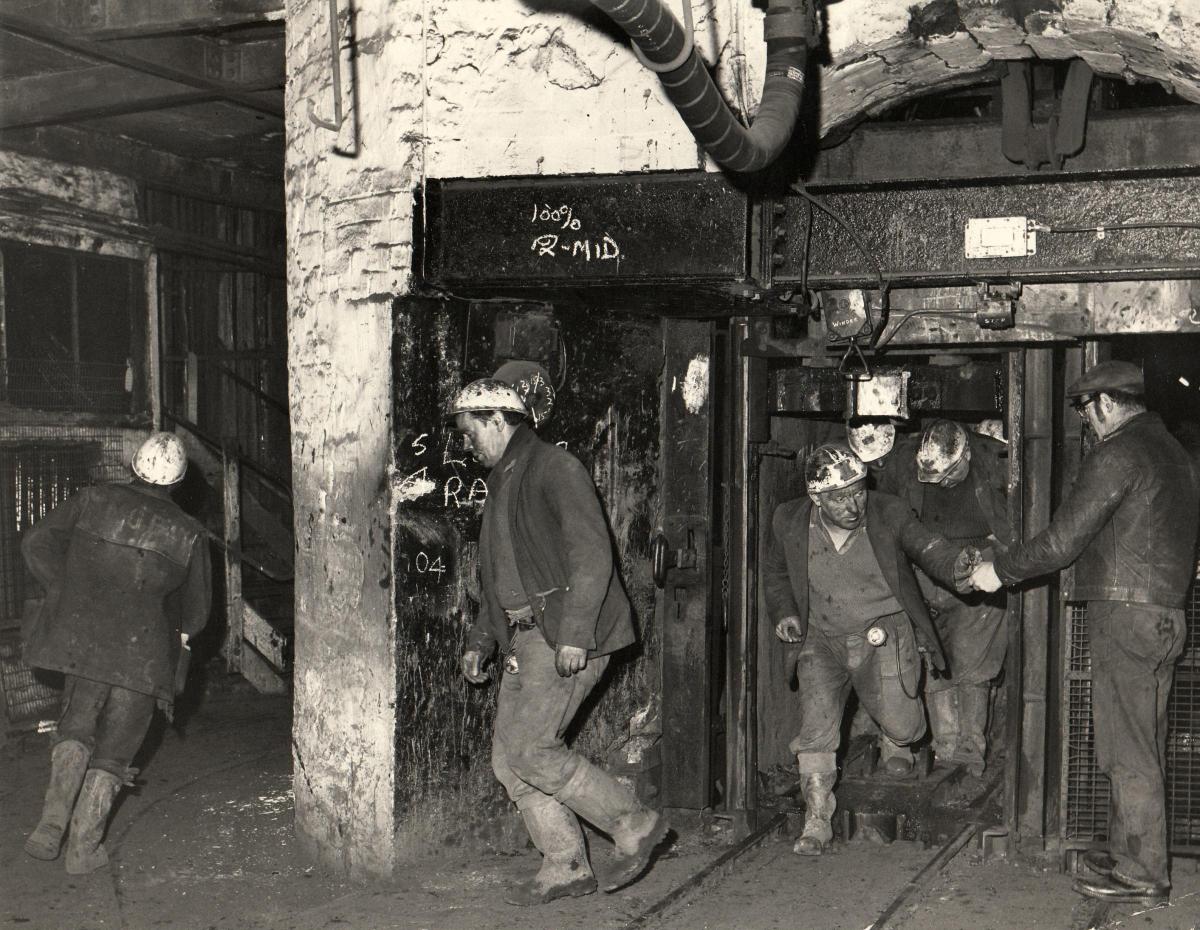

East Hetton Colliery was near Quarrington Hill and Kelloe, on high ground to the east of Durham City. The inundation occurred at 3.30am on May 6, 1897, when only 13 men were “in-bye”, or “in the workings”. They were the wastemen, tidying up between shifts – this was a huge colliery, employing nearly 1,500 men and boys, so it was a fluke that there weren’t hundreds down below to be swept away.

The Echo said: “Deplorable as it is, it is fortunate the accident did not occur sooner or later, a body of night shift stonemen leaving the seam at 1am, while the fore shift heavers were due down at four o’clock.”

The accident occurred when the old workings of Cassop colliery were “holed” into. Cassop had been flooded many years before and abandoned, and, in those days before Global Positioning Satellites, everyone thought it was some considerable distance from where the East Hetton lads were working.

But their positioning was all wrong. In fact, an enormous lagoon was directly above their heads, resting on the stone they were hollowing out.

To reach the coalface, the wastemen had walked 1,600 yards from the shaft bottom roads that were downhill all the way. Therefore, they were at the lowest point of the pit, and so when millions of gallons of water came crashing down on them, there was no hope.

Two men who had been furthest from the face, John Foster and John Stanton, had managed to escape. “With that determination which makes life sweet, they struggled on to the engine plane where they got hold of the tail rope,” said the Echo. Pulling on the rope, “although many times overhead in water, they managed to reach the shaft thoroughly exhausted and severely cut and bruised by coming into contact with iron rollers, floating timbers etc”.

One of them reported standing on the body of one of his less fortunate comrades as the great tide roared through the underground tunnels.

Once Foster and Stanton had been hauled out, the resident manager, Benjamin Chipchase, descended in the cage to survey the watery scene, “but it was at once apparent that nothing whatever could be done to save the lives of the 11 imprisoned men”.

Powerful pumps were brought in from across the coalfield to empty the pit, and the old Cassop shaft was hurriedly capped off because water was pouring in through it – even the old enginehouse was tossed down the shaft with 200 loads of clay tipped on top of it to keep the water out.

Gradually over the next few days, as Mr Chipchase watched, the water level in East Hetton dropped, but even though he and his rescue party waded waist deep into the darkness, they found no signs of life and no sights of the bodies.

But miraculously, four days after the initial inundation, when walking into the black water, Mr Chipchase found John Wilson alive on a high ledge.

“The rescued man, who was deputy-overman, was imprisoned in the mine without food or light for exactly a hundred hours, and when he was discovered, those who saw him regarded him with great surprise,” said the Echo.

He was, after all, supposed to be dead. The terrible news that the 30-year-old had was doomed had caused his pregnant wife to go into early labour and, said the Echo, “so confidently was it believed he had perished that his insurance money was paid over to his wife”.

Somehow, he survived.

“He was terribly exhausted, but he was able to tell his rescuer that when caught by the inrush of water, he attempted to make his way out by floating on props and pieces of old timber,” said the Echo. “He had no idea of time. In fact, when brought out, he did not know the day of the week, and thought he had only been underground one day, instead of four. He says that he never felt hungry, and that his mind was solely intent on trying to escape.

“His first words on coming to the surface were “it’s grand to see a sight of the bonny blue sky again”.”

Then he fell into a deep sleep.

Hope stirred in the stricken community – if John Wilson could survive the tsunami, perhaps the other men could, too.

But the hope was cruel. Six days after the inundation, nine of the ten lost men were discovered, their bodies unidentifiable because they’d been so disfigured by being churned around in the rushing water and because they had become swollen from lying in it for so long.

“The majority of the bodies were recognised by their watches, boots and clothing,” said the Echo. This identification allowed them to be returned to their former homes prior to their funerals.

Expressions of sympathy came from far and wide.

The Dean of Durham, Dr George Kitchin, sent a cheque for £2 2s and a letter to the local MP saying: “I am very sorry for the mishap at East Hetton. If a little help is allowable, I should greatly like to show that sympathy indeed to the widows and bairns. I should like to enclose a trifle with this, if you will be so kind as to transfer it to those who want it most.”

Nine funerals were held on May 14, 1897, in churches and cemeteries in the various villages around the colliery and then, a couple of days later, the tenth body was recovered. It was of wasteman James Oliver, 42, of West Cornforth.

Indeed, by the time of his funeral, John Wilson had recovered sufficiently to attend.

The Times reported: “He was buried in the coffin which had been made for Wilson, so that Wilson had the unique experience of following his own coffin to the grave.”

In fact, after three weeks off work, Mr Wilson was once more well enough to return to the coalface. He is said to have continued at the pit until he retired, and it is believed he died 35 years after the disaster which he had had no right to survive.

ON Saturday May 6, 2017, and so the 120th anniversary of the disaster – a memorial service will be held at 10.30am at St Helen’s Church, Kelloe. Banners from the Durham Miners’ Association lodges which lost men – Quarrington Hill, Kelloe, Thornley and West Cornforth – will be present along with those from the neighbouring lodges of Trimdon Grange, Bowburn and Wheatley Hill. Everyone is welcome to attend.

With thanks to Clive Lawson, George Tunstall, Keith Pounder and Bobby Robson for their help with this article

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here