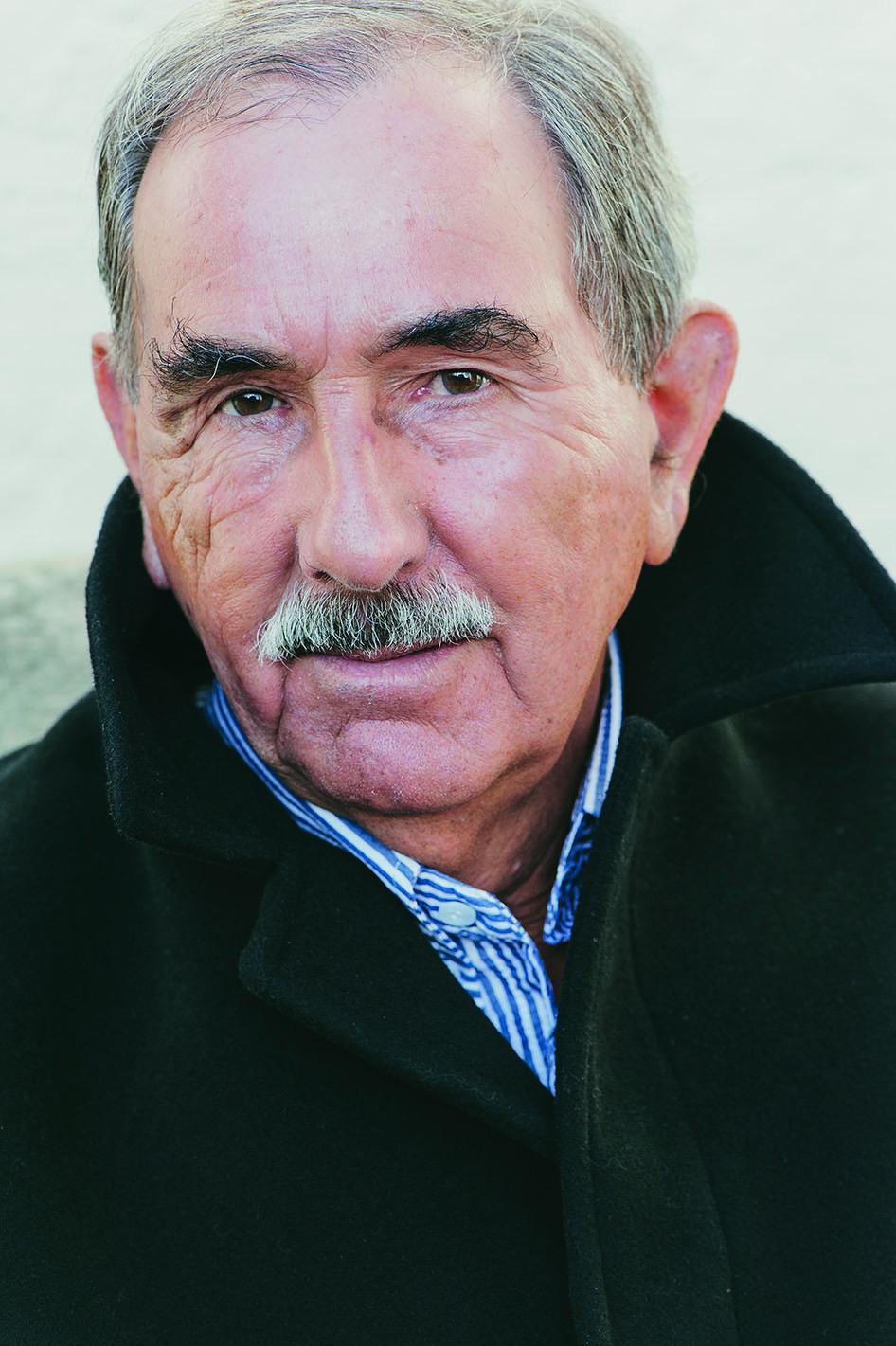

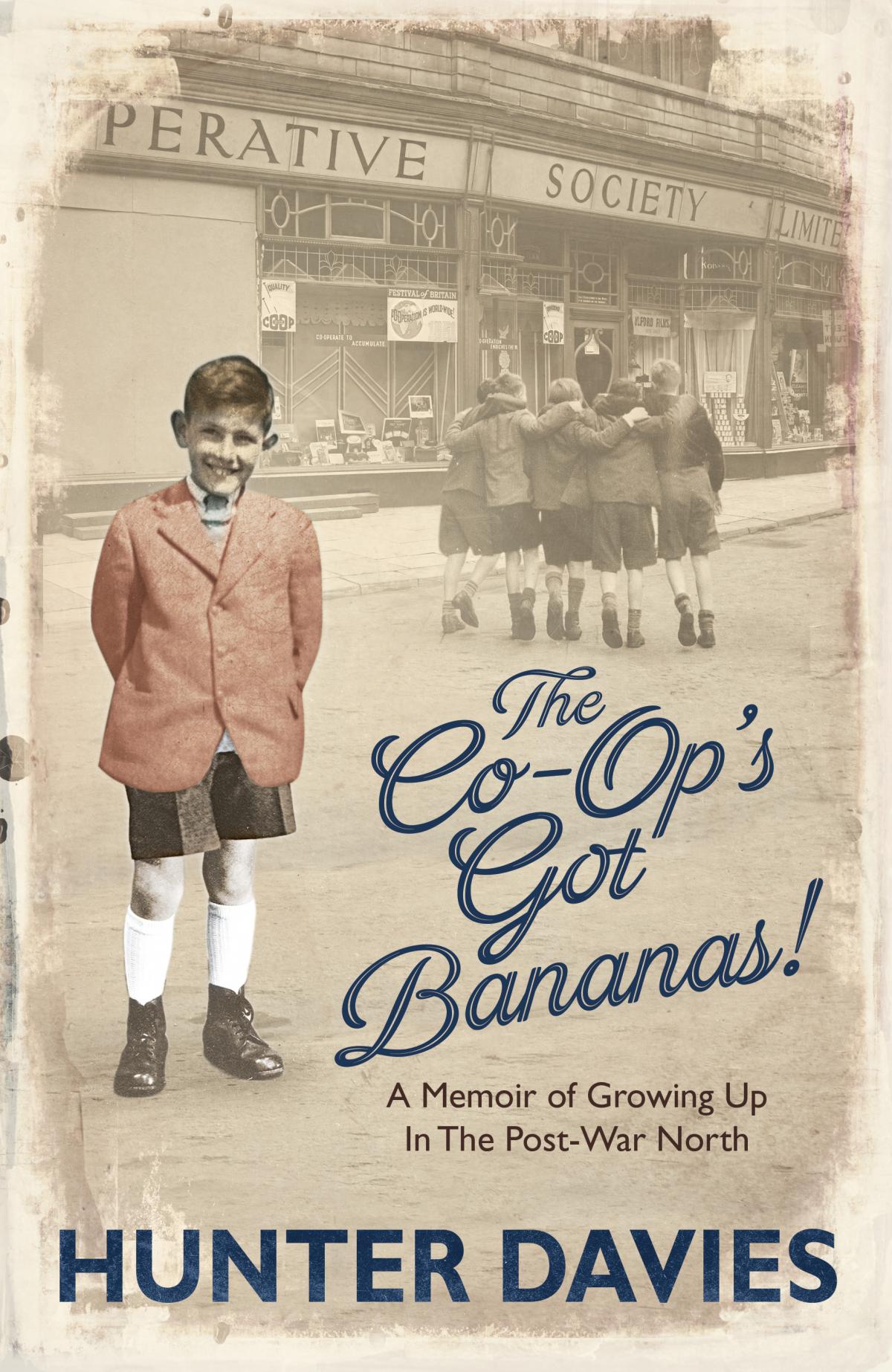

Harry Mead, and Mrs M, are entranced by an account of growing up in post-war Britain, with its rationing and rules, but also its freedoms, by noted columnist Hunter Davies

Who better than a contemporary to judge a portrait of growing up in a recent period of British history? So I handed this book – The Co-op’s Got Bananas by Hunter Davies – to my wife.

From various writings by the author, a noted columnist with publications ranging from The Sunday Times to Cumbria Life, she already knew that she and Hunter shared the same age. The book quickly revealed that their birthdays, in 1936, were just three weeks apart. It even turned out that in early childhood, Hunter aged four, my wife five, both moved with their families to Carlisle – Hunter from Johnstone, near Glasgow, my wife from York.

Amazingly, both soon moved again - my wife back over the Pennines, to Middlesbrough, Hunter to Dumfries. There the direct comparison ends. My wife remaining on Teesside while Hunter returned to Carlisle, with which, coupled with the wider Cumbria, especially the Lake District, he has enduring links. But their social backgrounds, with Hunter’s father a clerk in the RAF and my wife’s a commercial traveller for Rowntrees, were perhaps not dissimilar.

So what did Mrs M. make of Hunter’s recollections? Soon deeply absorbed in the book, she broke off to pronounce: “This is incredibly like how I grew up.”

A detail to make the point: my wife has often told of how, one day at junior school, she was sent, unaccompanied, to a bank, to deliver the takings from a pupils’ savings scheme. Here’s Hunter: “Some lucky child in some schools was given the job each Friday of taking all the shillings to the post office… I am amazed they never got mugged, or ran off with all the money, or lost it. Oh, we were so trusting then.”

Just two years younger than Hunter, to the very day, maybe I can add a validating word to Hunter’s picture? He recalls he was forbidden “to ride my bike on a Sunday or play football.” Well, one Sunday my scuffed shoes revealed to my parents that I had been playing football – which earned me a strong ticking off.

The dreary Sunday was very much a feature of those times. But Hunter correctly identifies a brighter aspect. “We who were there also remember the freedom, playing out all day long, going in the woods, building dams and dens, being allowed outside for hours with no-one bothering us, or wondering where we were.” And all streets were play streets - “no cars, of course, to interfere, or distract, or run us down.”

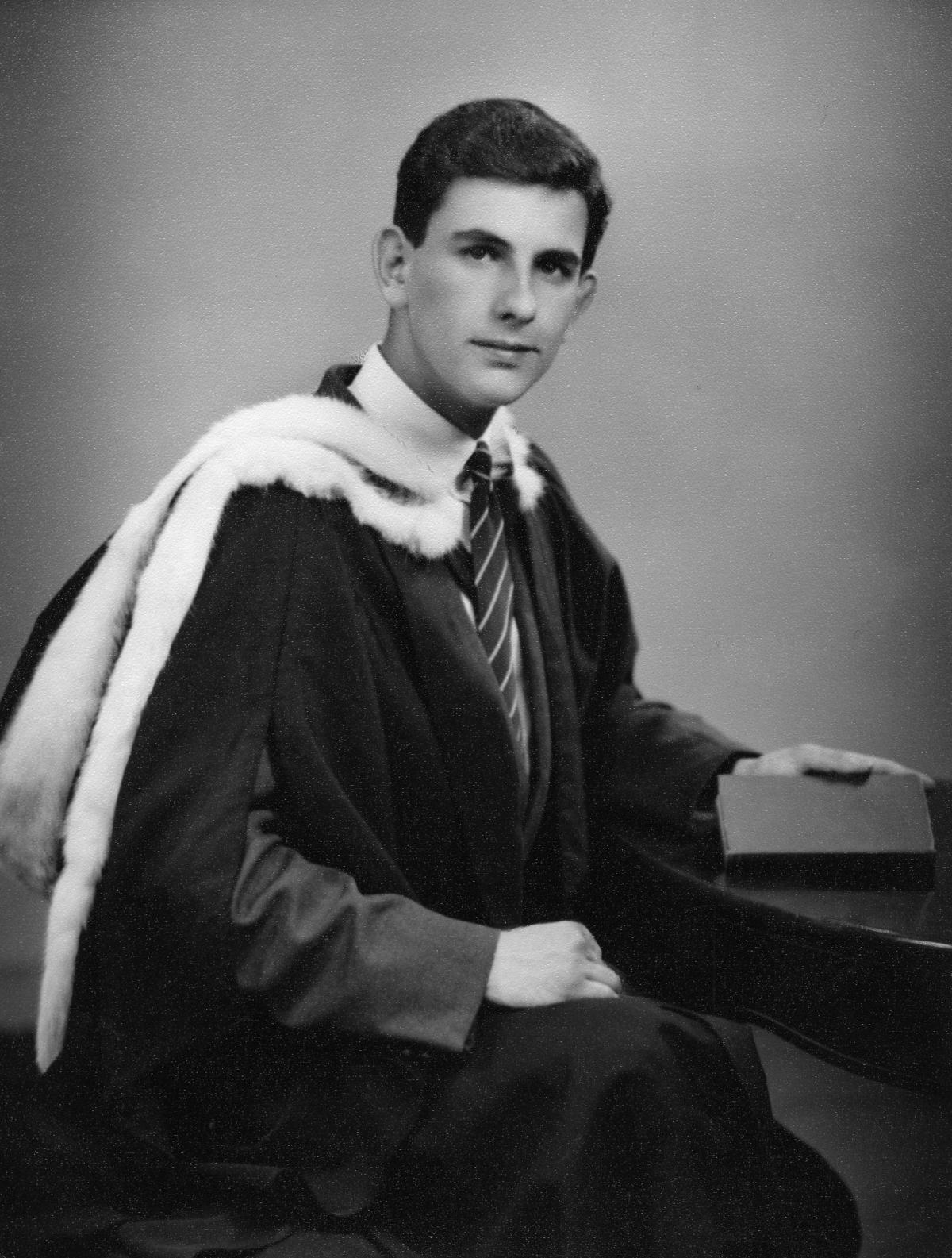

Failing the 11-plus, which he condemns roundly, Hunter later won a grammar school place and graduated from Durham University, where, for the first time, he “felt on equal terms.” Besides his journalism he has become a prolific author, with acclaimed biographies of The Beatles and legendary fell-walker Alfred Wainwright among his credits.

Though not taking readers that far, he describes his university years and his early career in journalism, centred on Manchester, then the ‘Fleet St of the North’. Notable names that figure include Harry Evans, the illustrious former editor of this newspaper. Hunter writes that the future Sir Harold, then assistant editor of the Manchester Evening News, failed to secure the economic correspondent’s post with the BBC. His move to The Northern Echo “seemed a bit of comedown, going back to the provinces, compared with the media heights of Manchester”.

Oh dear! But let’s not bridle. The best of Hunter’s book deals with his boyhood and adolescence. Yes, there are girls – and gropings for that matter. “Who would have imagined”, muses Hunter, “that teenagers today would be sending photos of their genitals to each other?… How sheltered we were. But do we want it back? Or do we envy the fun and freedom of today? Discuss.”

We meet Hunter’s future wife, Margaret Forster, destined to be a successful novelist. She died shortly before publication of this book, which adds poignancy to Hunter’s dedication to her - “the best thing that ever happened to me.” The “awful, divisive” 11-plus aside, other subjects earn serious comment: Unmarried mothers, for example. Comparing the “money, housing and support” they now receive with the shame and disgrace they faced former days, when their newborn children were often taken from them, he declares: “I happen to think this is an advance.”

Hunter’s first trip abroad, to France in 1952, causes him to reflect that much of the novelty of foreign travel has vanished. “You have to go much further in the world to feel truly abroad these days. Or stay in London. That is probably today the most exotic city in the world.”

Only rarely do Hunter’s recollections let him down. ITMA was “probably the most popular wartime programme”. No probably about it, Hunter. People lined the streets and wept at the funeral of Tommy Handley, the comedy programme’s star. Wilfred Pickles, affable host of the radio quiz Have A Go, “had a strong Lancashire accent”. Yorkshire, Hunter, Yorkshire. But what would a Scottish-born Cumbrian know about that?

So what of the book’s titular bananas? Hunter was playing football in Dumfries when, as he recalls, “I heard a cry go up from the other side of the park: ‘THE CO-OP’S GOT BANANAS!’... We all stopped playing, listening carefully, checking to make sure we had heard the words correctly, then we took up the same refrain: ‘THE CO-OP’S GOT BANANAS!’ We rushed out of the park, down the hill, and were joined by gangs of other kids till we were a large crowd, all chanting ‘The Co-op’s Got Bananas.’ ”

For Hunter this seismic event “signalled the end of the war”. Many might agree. I remember staring at my first banana as though it were a wonder of the world. I’ve never really liked bananas, and Hunter admits he preferred the taste of the mashed parsnips his mother had served up as a wartime substitute. But whether you were there or not, you are unlikely to find a more entertaining yet accurate account of growing up in post war Britain than in this richly-enjoyable memoir.

The Co-op’s Got Bananas by Hunter Davies (Simon & Schuster, £16.99)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here