ANCIENT records for a village graveyard show that a surprising number of people from other places were laid to rest there.

The first burial in the grounds of St Mary’s Parish Church, in Cockfield, was registered in 1578. Most of those interred in the following centuries were from that village or Woodland, which had a close link.

But there were also regular burials of folk from Ramshaw, Evenwood, Wham, Butterknowle, Toft Hill, Staindrop, Shotton, Hindon, Langleydale, Hamsterley, Wackerfield, St Helen Auckland, Gainford, Morley, Heighington and other places which are hard to make out in the registers. There was no explanation for such a wide spread of addresses of the deceased.

An exception was made for George Chisman, who died in 1874. His entry shows he lived in Ovington but died in Cockfield. This could be the explanation for others, and some could have a family connection with the village. There is unlikely to be any other graveyard in the dales with occupants coming from such a variety of places.

The registers give occasional brief descriptions of those buried, such as: February 16, 1615, Robert Dixon, parson of Cockfield; January 20, 1639, Will Robsonne, scoolemaster; August 11, 1687, Elizabeth Sedgewick, parson; May 2, 1690, Tobias Sedgewick, minister of this place; January 3, 1711, Frances Coalmen, clerk to ye parish; November 1, 1768, James Ridley, a pauper sustain’d by ye township; March 24, 1773, Isabella Allison, poor woman concubine to GM; May 12, 1797, Joseph, son of Hannah Watson, a love begot child.

There are a number of entries for men and women described as poor travellers or children of poor travellers.

Many others were simply said to be poor.

The original ledgers dating from 1578 to 1799 were all difficult to read as pages were frail, handwriting was often unclear and spelling was sometimes chaotic. But all the details can be read easily now, as they were painstakingly studied and typed out by Kim Wasey and Terry Lockhart in 2000.

It was a mammoth task involving no fewer than 1,468 deaths. Their work was edited by the Reverend Ian Gomersall, vicar at the time.

Kim Wasey did further good work in making an index of more than 550 burials between 1800 and 1840.

It is much easier now than in the past for families to search for items about their ancestors.

The saddest feature of the documents is the high number of infant deaths, with so many children dying under the age of one, and a lot of others not getting past school age. At the other end of the scale, John Smurthwaite was 104 when he died on December 23, 1805, and Mary Allison, of Mount Slowly, was 100 when she passed away on October 30, 1822. There were a sprinkling of others who got near the century mark and a fair number reached their 80s. But generally people had shorter lives than they do now.

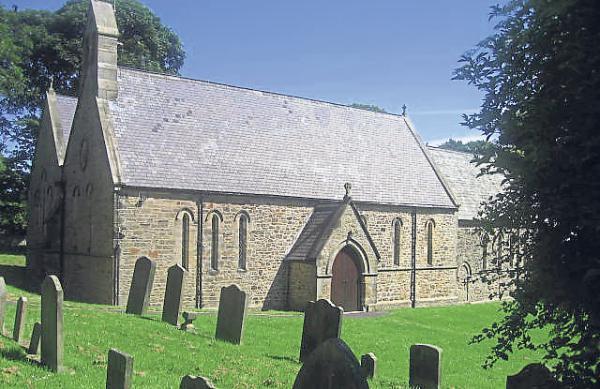

John Hallimond kindly loaned us his copies of the documents. The church dates from the early 13th Century, but was restored in 1868.

MANY dale farming families had sons killed in the First World War, but Joseph and Mary Jane Jemmeson suffered more grief than anyone else in the agricultural community. Three of their four sons died after going off from their farm in Langleydale to fight for king and country.

Wilfred Ernest, known as Fred, a 19-year-old private in the Yorkshire Regiment. was killed in action near St Quentin, in Northern France, in March 1918. His name is honoured on a large memorial at Poziers.

Then Thomas, who was 30 and a private in the 2nd Battalion DLI, was struck down at Etretat that October. He had a leg amputated as doctors tried to save his life, but he died in an American military hospital and was buried in France.

After the Armistice in November, it seemed George Edwin, who was 19 and a second lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, would survive the hostilities. He was mentioned in despatches for courage, but then died when a light aircraft in which he was an observer crashed while attempting to land in May 1919. The pilot was also killed. It happened at Chechin Island, in Russia, where fighting continued after peace was declared elsewhere. He was described as an outstanding young officer and a favourite in his unit.

King George V and Queen Mary sent a message of condolence from Buckingham Palace to Mr and Mrs Jemmeson, who by that time were living in Baliol Street, Barnard Castle.

Their other son who served in the war lived into his 80s. John Pringle, who researched all the names on Barnard Castle war memorial, provided details of the tragic brothers.

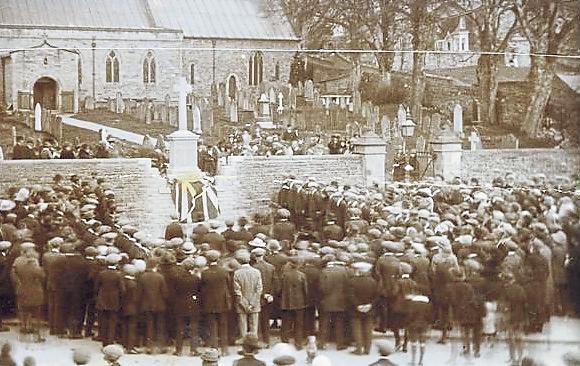

LAST week’s item here about Stanhope war memorial mentioned that the unveiling ceremony in 1922 was attended by a large crowd.

This is confirmed by a fine photograph of the ceremony loaned by David Heatherington, of the Weardale Museum. It shows the main dignitaries and clergymen who took part, as well as the families of the 33 local men who gave their lives in the First World War.

Those named on the memorial are J.W. Allison, T. Atkinson, O.

Bainbridge, W.H. Bainbridge, J.

Barkess, J.H. Boyd, J.F. Bright, H.

Coulthard, H. Denham, W. Denham, H. Dennison, A. Emerson, C.J.W.

Forster, G.E.Gibbon, H. Golightly, G.T.Hayton, T.W.Hind, J.Jackson, J.T.Monkhouse, J. Pattinson, A.

Raine, J.G. Raine, R.R. Ripley, J.W.

Rutherford, A.W. Stockdale, A.W.

Tweddle, J.Vickers, H. Wallace, J.T.

Walton, J.R. Ward, M. Ward, I.N.

Wearmouth and A.D.Woodhall.

IT was common to see tramps wandering all over Weardale, Teesdale and other rural areas over a century ago. But there were fewer of them around on Sundays.

Those gentlemen of the road were not good for the image of any area, especially if there were too many of them at one time. Some were dirty and untidy, and they could be a nuisance if they called at houses, or stopped people in the street, asking for food or money.

So, in the 1880s, when they checked in for a bed in workhouses on Fridays or Saturdays, efforts were made to keep them there on Sundays.

Officials explained at Barnard Castle workhouse that the aim was to keep vagrants off the streets and highways on Sundays. After all, residents going to church or having a peaceful walk on their day off did not want to be faced with grubby old strangers.

The official reason was that, after being allowed in for a free bed and meal, the tramps had to carry out some work before leaving. There was no system for giving them work at weekends, so they had to stay and do their task on a Monday.

Some protested that if they stayed on a Friday night they could do any necessary work on Saturday and then be allowed to leave, but in many cases that was not accepted.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here