THERE was widespread sorrow and anger in the dales after a penniless man died in prison, soon after being taken there in a seriously ill state for not paying a £2 fine.

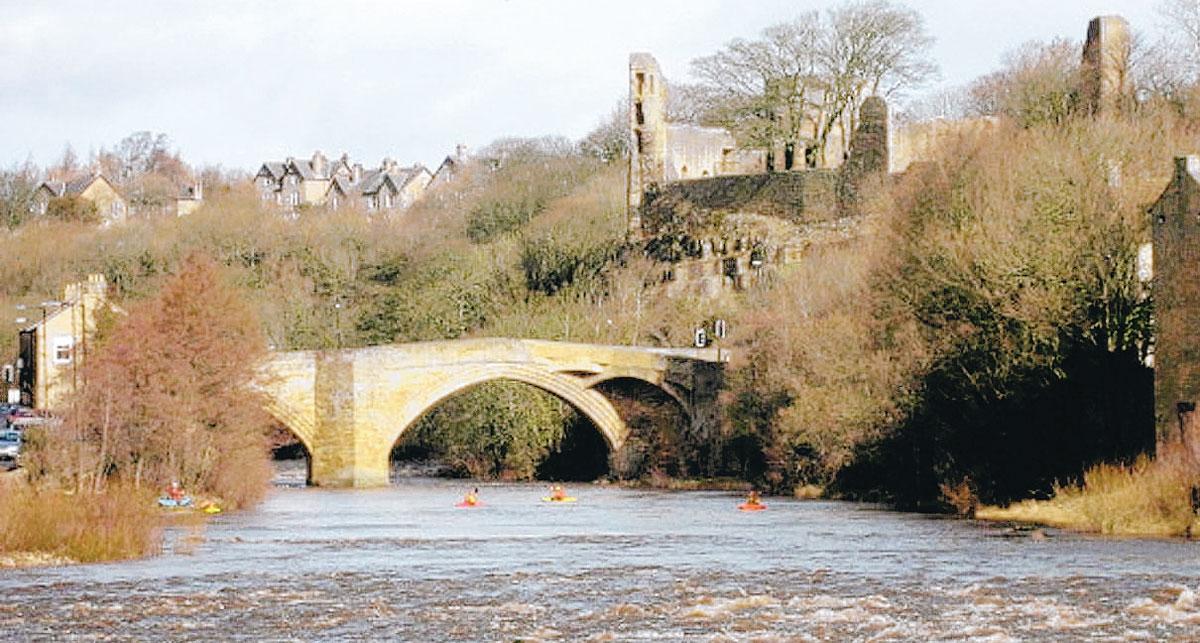

Joseph Head, 33, was charged with possessing a salmon which had been caught in the River Tees near his home in Thorngate, Barnard Castle.

When due in court he was in hospital at the town’s workhouse suffering from consumption, now better known as TB.

His father handed in a sick note to explain his absence. The case was adjourned but when it came up again he was still in hospital. The magistrates imposed a £2 fine in his absence, with a month inside in default.

Next morning, Christmas Day 1885, police took him from the workhouse to Northallerton Prison for not paying, and he died there seven days later on New Year’s Day.

During his final week he was kept in the prison infirmary and was so ill that two other prisoners were detailed to sit watching him through the night. They were alarmed to see him coughing up blood.

An inquest at the nearby Harewood Arms was told he suffered from consumption and death was due to rupture of capillaries of the lungs. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with this evidence.

A big crowd was at Barnard Castle station to see a black coffin containing Joseph’s body arriving on a train. A group of his relatives and friends carried it to the cemetery. A burial service was conducted by Canon Frederick Brown. But many questions were left.

Why did the JPs not check whether Joseph was still in the hospital, which was only a few minutes’ walk away? Why did police remove such an obviously sick man from the hospital? Why was no effort made to raise £2 from his family or friends?

Concern was raised by the board of guardians who oversaw the workhouse.

They asked why the master allowed police to take away an ailing inmate. He replied that he had no power to stop the police doing anything.

The authorities decided no one was to blame.

It was pointed out that Joseph’s condition did not seem as serious it proved to be. He claimed he knew nothing about the second court hearing but had no money to pay the fine and did not protest about being taken to jail. It was a hard winter with many men out of work. Some tried to snaffle fish or rabbits to feed their families but police and gamekeepers were often in hiding to try to catch them.

AFTER a recent piece about Jack Blenkinsop’s 40 years as a postman, a reminder came about John Walker, who delivered the mail for 43 years. He lived in Eggleston and did the round there from 1893, taking over from his father, who served for 25 years.

John had a horse and trap to do the widespread route at first. But in the severe winter of 1895-6 the snow was so deep that the trap could not be used. He had to saddle the horse, which was 16 hands high, and ride it to every house and farm on the round, often going over walls and gates.

He did not see the ground for three months that winter, in which thousands of grouse and partridges were frozen to death. One Christmas, he had a small package to deliver to a woman who lived three miles from the post office. When he reached her home he realised the package was missing, so he went back to the office looking for it.

THe then turned and headed back again – and came upon the vicar, who had found the missing item in snow on his doorstep. The relieved postie carried on to deliver it, and the woman who received it was just as relieved. It contained her false teeth, which had been away for repairs.

“I wouldn’t have been able to eat my Christmas dinner without them,” she told him.

He served in the Royal Engineers in the First World War as a smith, fitting shoes on some of the many horses used in battle. His postal experience stood him in good stead, as he often had to travel between units on horseback.

He saw battle action at Ypres, Verdun and Haynes Park and was in hospital for 62 days through illness.

After the war he returned to his wife, Mary, daughter of the landlord of the Three Tuns Inn, and their daughters, Doris and Margaret. He soon resumed his Eggleston round but eventually switched to a bicycle and then a van. He also served as a parish councillor. He was awarded the Imperial Service Medal when he retired in 1939 and received gifts from grateful residents.

HERE would be an outcry today if an employer asked young women applying for jobs if they were courting – and then rejected those who answered yes.

But this happened in the dales in the past when young nurses were interviewed for posts in workhouses.

Qualified nurses were needed because there was often illness among the inmates, especially children and elderly people. But those who came from other areas had a habit of staying for a few months rather than years, because they had left boyfriends behind and went back to marry them.

It happened repeatedly in Barnard Castle and was reported at an area meeting of guardians in Crook in 1939. It meant spending a lot of money on advertisements every time a new nurse was needed, and the cost had become excessive. The area officer, M.J. O’Sullivan, suggested that in future when young nurses from other districts applied for jobs they should be asked right away: “Are you courting?”

If they said they were, they should not be appointed, because before long they would probably want to go back and get married. But if they were not courting they might meet a young man in this area then get married and settle here. The guardians agreed it was a good idea and said the question should be asked when nurses were required in future.

Some applicants must have been bemused when they realised the matter of whether or not they had a boyfriend was more important than their results in nursing exams.

HENRY NELSON wandered all over the dales for much of his life, doing odd jobs here and there to earn a few shillings and often sleeping rough.

Many folk knew him by sight but didn’t know his name because he was always referred to as Baccy Harry. Tobacco was his main pleasure.

He was never happy unless he had some to chew or smoke.

If he only had a copper or two he would spend it on baccy rather than food. If any kind person wanted to give him a small gift to help him on his way they knew what he would like most of all.

He was born in Barningham in 1843 and lived there with his mother when not tramping round Teesdale and Weardale as well as venturing as far as Ripon at times. He kept meandering after his mother died when he was in his 50s. But he returned regularly to the Barningham area, where several people gave him occasional jobs which earned him small sums. It was on one of those visits that he died at the age of 69 in 1912.

He called on John Atkinson, of Wilson House, where he was given some gentle tasks to do, and where Mrs Atkinson could always be relied on to give him some food. He worked for a few days before his body was found in a field.

It was a peaceful end in a convenient place. He was buried in Barningham churchyard after a service attended by about 30 people, who had memories to share about the strange life of Baccy Harry.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here