A landmark anthology will define North-East poetry for years to come, says Harry Mead

Where in this abhorrent land of power and pick,

man, muscle, machine, sweat and toil,

could a man find peace and contentment…

What fascination does this stumbling

place still hold for me?

That ‘place’, back in 1974, was Sunderland. But its image of ‘man, muscle, machine, sweat and toil’ – is classic North-East, in its lost industrial past. The poet, Ron Knowles, provided more detail – ‘shuffling trains’ bearing ‘freshly-hewn coal’, while, abutting ‘ragged streets’ had sprung up ‘busy, booming shopping centres…The old, too old. The new, too new.’

Yes indeed. Knowles didn’t answer his own question – a poet’s privilege, perhaps. But, during a year spent as poet in residence at Sunderland’s Austin and Pickersgill shipyard, another North-East poet, Tom Pickard, was struck by the workers’ pride in their skilled and often very physically-demanding work. Asking What Makes a Makem? he concluded: ‘A Makem can / weld himself into/ a steel box/ and seal the lid on/ afterwards.’

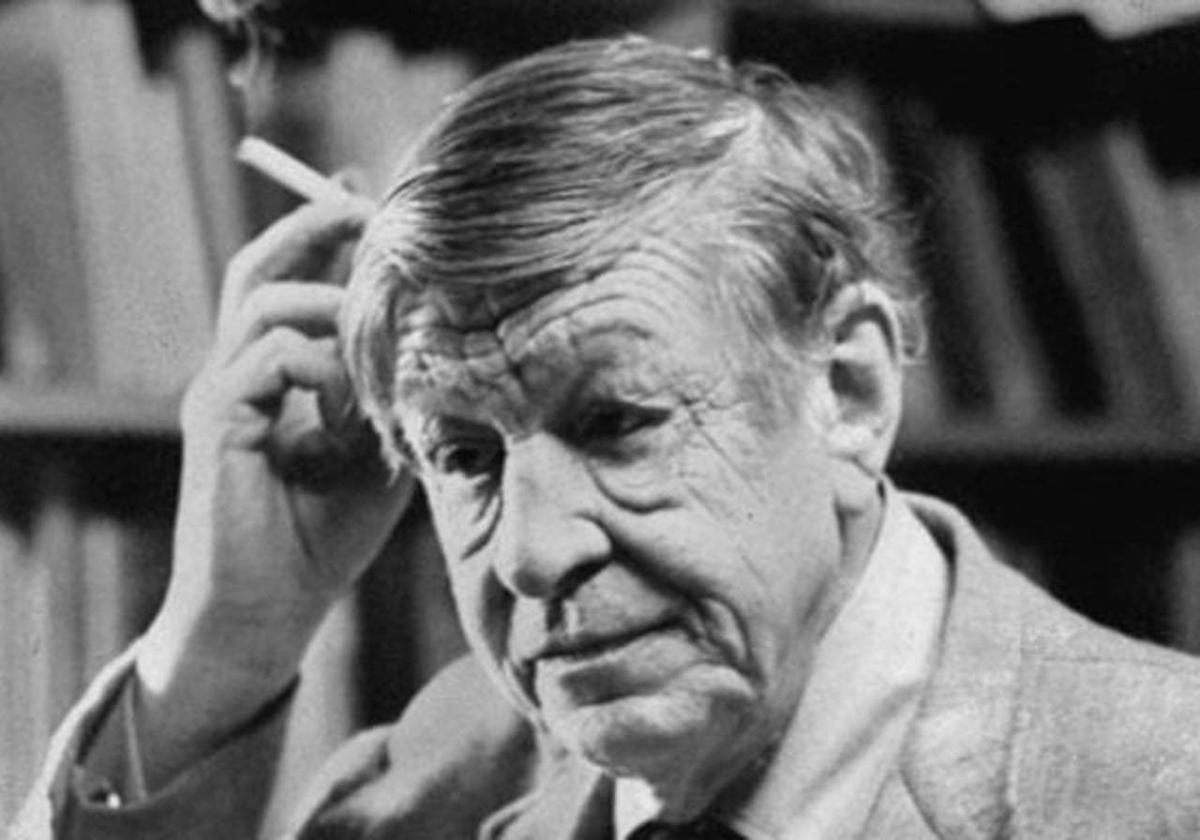

Of course the North-East is more than Wearside and the region’s larger former industrial heartland, chiefly east of the A1. Far out west stand the vast, sweeping hills of the North Pennines. Dubbed England’s last wilderness by some, to York-born WH Auden, one of the two of three leading poets of the last century, the area from Swaledale to Hadrian’s Wall was what he called his ‘great good place.’

But even there it was chiefly the industrial past that gripped Auden’s imagination. His 1924 poem Rookhope opens: ‘The men are dead that used to walk these dales;/ The mines they worked in once are long forsaken.’ A few years later he captured the remoteness: ‘This land, cut off, will not communicate…/ Beams from your car may cross a bedroom wall, / They wake no sleeper…’

Long before Auden, a more humble poet, Teesdale’s Richard Watson, was more intimately acquainted with much of the same ground. His poem My Journey to Work records his seven mile trek from Holwick to a lead mine at Little Eggleshope: ‘The rugged up-hill walk and sun’s hot rays/ Cause the warm sweat to trickle down the face, / Yet pushing on, the path an ascent still, / Till on the top of bleak Hardberry Hill, / Where sitting down, my wearied limbs to ease, / I, looking back survey the Vale of Tees…”

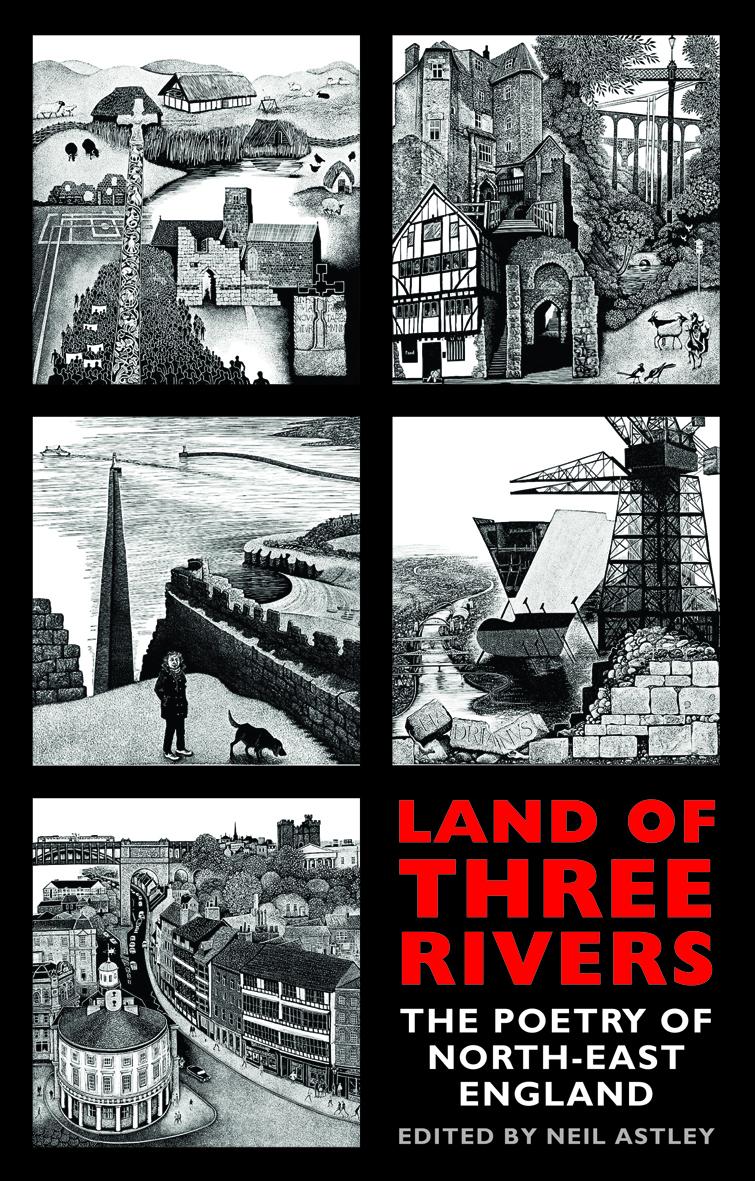

All these poems, and many, many more distinguish an outstanding anthology*, the central wonder of which is that nothing like it has appeared before. But it arrives as a tour de force, for which the word ‘landmark’ might well have been coined. Containing 517 poems in all, it begins with the general and proceeds through 16 geographical sections, each worth identifying here to reveal the anthology’s scope: Hadrian’s Wall; Jarrow; the Borders; North to South Northumberland; North Tyne, Redesdale and Coquetdale; Tynedale, South Tyne and North Pennines; Newcastle (the largest section, 56 poems); Gateshead; North Tyneside; South Shields; Wearside; Durham City; Co. Durham; Teesdale; Middlesbrough; Cleveland.

Phew! Somehow, the region’s prime obsession, football, seems to have escaped close poetic attention throughout. But Newcastle ale is present, championed poetically as far back as the 1760s. And, in our time, Tony Harrison, an interloper from Leeds, weds a nod to the local brew to a sly dig at the Geordies’ devotion to the Magpies: ‘The Brown Ale drinkers watch me as I write’. But they don’t know the two hopes he has just expressed - ‘jobs for all of you – / next year your tattooed team gets relegated.’

In other poetic hands the Angel turns up too. Is there ambiguity in the lines by Jen Campbell: ‘She is rusted like the ridges along the tops of tin cans…/ Her arms reach out to touch the sky. I think she does not touch it’? No such doubt clouds Andy Croft’s celebration of the Great North Run: ‘Where old Misrule rides round on Shank’s mare, / The world’s turned upside down for just one day/ And every tortoise gets to beat the hare; / A race with 40,000 losers/ Where every loser knows themselves a hero, / The biggest heroes are the wheelchair users…’

With informative notes on poets and poems, this anthology will define North-East poetry for years to come. So it’s a great disappointment that the Cleveland section, with just five poems, is so pitifully sparse. Good enough to hold a place in the Oxford Book of English Verse, the Lyke Wake Dirge is absent. Indeed, the entire, rich field of Cleveland dialect verse, practised by poets like the late Bill Cowley, founder of the Lyke Wake Walk, is ignored - or perhaps undiscovered.

A related regret is that since the collection kicks off, historically, with the song of Caedmon, the Whitby Abbey cowman regarded as the first English poet, there’s nothing by Whitby’s Tom Stamp, a delightful poet who died in 1991. Tom’s Whitby in Winter (final words ‘And everywhere is the sound of the sea’) is a particular gem, and many readers might have found Tom’s tribute to Caedmon, in whose name he and his wife Cordelia founded and ran a micro publishing company, hit the spot more effectively than the anthology’s imported choice, by a Cumbrian poet.

But modern song lyrics, by the likes of Sting and Alan (Fog on the Tyne) Hull enjoy a place alongside old favourites such as Bobby Shafto and, of course, The Blaydon Races. Before his untimely death last June, Vin Garbutt, Teesside’s legendary folk-song singer and writer, was looking forward to singing his John North, the anthology’s opening ‘poem’, at the book’s recent launch.

An 18th century poem, The Collier’s Wedding, brings bawdy humour to the anthology, and there’s plenty that’s more subtle. Robyn Bolam, once of the North-East, now in Hampshire, draws it from even the industrial decline which – make of it what you will – is the anthology’s dominant theme: ‘When the shipyards closed, cranes were last to go -/ sold to India along with the dry dock. / I wondered how they dealt with the shock of heat.’

*Land of Three Rivers: The Poetry of North-East England edited by Neil Astley (Bloodaxe £14.99)

From ‘Between Stations’

These lines link the closure of Redcar steelworks with a crushing defeat of Yorkshiremen by William the Conqueror at Teesmouth in 1069.

This was all marshland once; hidden slag heaps

lie under grass-covered bumps lining the sides

of trickling inlets of the Tees with its metal cranes…

and now no entreaty too could save the Salamander

in the lone blast furnace: the fiery heart – the last survivor

of the hundreds that lined the river banks an age ago,

making this the land of dragons with satsuma skies

welcoming the Welshmen who came to Eston mines,

recent death by neglect the final chapter of the onslaught

begun back then by the blunt-headed warrior king

they cared to name our next Prince of Wales after.

Andy Willoughby.

From ‘Forgotten of the Foot’

The title refers to an Old Testament phrase - They are forgotten of the foot that passeth by - inscribed on the Miners’ Memorial in Durham Cathedral.

No more, no more. They’ve swept up the workings

As if they were never meant to be part of memory.

A once way of being. A dead place. Hard livings

That won’t return, grim tales forgot as soon as told,

Steaming from the roofs in smoke from a lost century –

A veil of breath in which to survive the cold.

Anne Stevenson.

From ‘Darlington Fifty Years Ago’

I stood on Bank Top when meadows were green

Where little but Cuthbert’s tall spire was seen…

'Twas here in days past, when through its lone vale

The Passenger Coach ran on the first Rail,

A model for those in each country and clime

To traverse with speed through the boundaries of time.

John Horsley, 1889 485

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here