ONE afternoon in the middle of August, 1940, five sections of 607 (County of Durham) Squadron were scrambled in their Hawker Hurricanes from their home base at RAF Usworth, a few miles east of Sunderland.

Their orders were to intercept two formations of between 40 to 60 Heinkel and Dornier bombers which were approaching the Northumberland coast at 12,000ft. It would be an encounter of enormous importance in the early days of the Battle of Britain.

AT ten o’clock on the morning of Thursday, August 15, 1940, 141 German aircraft had taken off from their bases in Norway to launch a raid against the North-East.

Newcastle, Sunderland and Middlesbrough were their principal targets, along with RAF airfields at Dishforth and Usworth.

This was the first occasion on which 607 had been scrambled since it had returned in May 1940 from France, where for six months it had flown ageing Gloster Gladiator biplanes to give aerial support to the ill-fated British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

The French expedition led, of course, to the BEF’s evacuation from Dunkirk, but it turned the men of 607 into battle- hardener fliers and they put the experience to good use in the battle over the North- East skies that August afternoon.

It was a brief battle, 607 landing back at Usworth 30 minutes after taking off. They suffered no losses, but they shot down eight enemy aircraft and badly damaged six others. Altogether on that day, the Luftwaffe lost 75 aircraft and afterwards called it Black Thursday.

It had been prevented from inflicting the damage it had hoped on its targets, but, as Echo Memories told a fortnight ago, it still caused great misery. Its bombs killed 32 people were and injured 105.

Yet the fierce defence put up by 607 and the other Northern squadrons meant the Luftwaffe never again sent such numbers against the North- East.

The squadron had not started life as a fighter unit, nor was it the first squadron to be based at RAF Usworth, an airfield which started life during the First World War.

In October 1916, it was known as Flight Station Hylton or West Town Moor, with part of 36 Squadron based there.

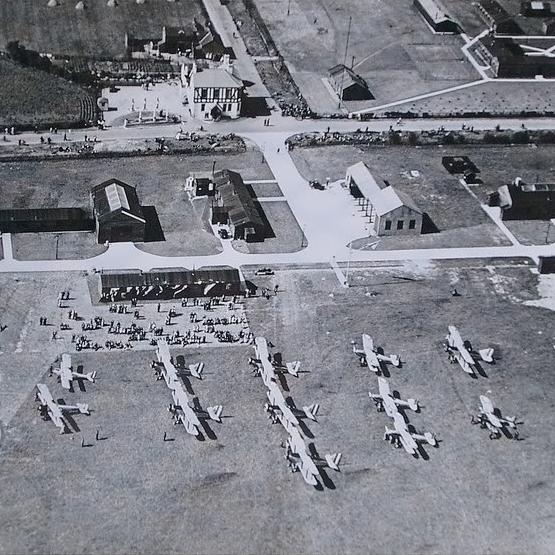

When the war ended in 1918, the land reverted to its original use until, some 12 years later, a new airfield was built on the site to accommodate a new Royal Auxiliary Air Force unit, 607 (County of Durham) Squadron.

Formed on March 17, 1930, as a light bomber unit, the Westland Wapiti biplanes 607 was told to expect did not ultimately arrive until December 1932.

Four years later, 607 was issued with Hawker Demons and re-designated as a fighter squadron in September 1937.

Its Gloster Gladiators were delivered in December 1938, but it was not until September 1939 that work began on the creation of two concrete runways and concrete bays for 34 fighter aircraft.

Also created at that time, but the work not finished until March 1940, were new buildings and anti-aircraft guns.

There was no rest for the County of Durham squadron after its heroics of August 15.

On September 8, it was moved to RAF Tangmere, in West Sussex, swapping with 43 Squadron ,which came north to Usworth to recuperate having borne the brunt of the Battle of Britain.

Now 607 was in the firing line, and at 5pm on Monday, September 9, more than 300 German bombers with their usual fighter escort crossed England’s South Coast and made for the Thames Estuary.

Their target was again London.

The RAF controllers, however, were ahead of the game and had already scrambled 24 squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes from Kenley and Biggin Hill to patrol over south London, from Hornchurch to guard northern Kent and from Northolt as cover over Folkestone.

607 (County of Durham) Squadron was deployed over the area of Surrey sky between Guildford and Biggin Hill.

With Squadron Leader JA Vick at its head, 607 met a group of the German intruders over Mayfield, in Kent, attacking the 60 or more bombers before their fighter escort could fly into a position to defend them.

As the 12 Hurricanes engaged the enemy, between 40 and 50 Messerschmitt 109s joined the fight. 607 brought down one Dornier bomber, but lost Pilot Officers SB Parnell and JD Lenahan, both shot down over Cranbrook, while J Landsell, RA Spyer and PA Burnell- Phillips were wounded. Pilot Officer G J Drake, a South African, was posted as missing and later found to have been shot down and killed over Mayfield.

The casualty rate for these men was terrible – Landsell was killed eight days later, Spyer in March 1941 and Burnell- Phillips in an accident, also in 1941.

After a busy month at Tangmere, 607 was posted north to RAF Turnhouse, in Scotland.

After a brief stay at Usworth as 1940 gave way to 1941, 607 returned to Scotland and in March 1942, it began making its way to India, a journey which took two months.

For nearly three years, receiving its first Spitfires there in September 1943, it saw service at numerous airfields in Bengal and Manipur, until it was despatched to Burma in April 1945.

On July 31, 1945, having served with distinction throughout the war, 607 Squadron, like so many others, was disbanded but re-formed at RAF Ouston in May 1946 when the Royal Auxiliary Air Force was brought back into being.

Its final years were spent at Ouston, Thornaby, Linton- on-Ouse, Acklington and, finally, Ouston again where it was disbanded in March 1957.

During its last years, 607 was equipped with the powerful Spitfire Mark XXII and flew into the jet age with the De Havilland Vampire.

On May 22, 1960, on the occasion of the presentation and laying up of 607 (County of Durham) Squadron’s standard in Durham Cathedral, a Mark I Hawker Hurricane, flown by 607 Squadron while serving in France in 1940 and during the Battle of Britain at Tangmere, was proudly displayed on Palace Green.

The day workers’ ship came in

PERHAPS the unluckiest German pilot was the one who had Haverton Hill in his sights at 9.15pm on Wednesday, September 18, 1940, writes Chris Lloyd.

Spread out beneath him was the Furness shipyard, with eight ships on the berths in various stages of construction.

“Some were nearly completed and some just had the keel with a few ribs,” remembers Bill Burnett, who was an 18-year-old apprentice shipwright at the time.

“I’d joined the shipyard when I was 14 and when the war started I tried to join the Navy twice, but I was sent back because I was in an essential occupation,” says Bill, who now lives in Billingham, near Stockton.

On the night of September 18, the yard was fully occupied building cargo ships and oil tankers for the war effort.

They must have looked like sitting ducks laid out beneath the bomber.

“He dropped a stick of four or five bombs across the yard,” says Bill. “He landed two on the railway lines in between the ships, and one on the pre-fabrication shed. As they landed so close, they lifted at least one ship out of the water and dropped it back down again, so it had to be resighted to make sure it was straight.

“There were some shrapnel marks on it, but that was it.

“The German bomber must have been the most unlucky of the war. He missed every ship.”

One bomb overshot the yard and demolished the Glass family home. “They had to be dug out,” says Bill, “because they were sheltering under the stairs.”

The Northern Echo of the following day 70 years ago said only of the incident: “A German plane which flew over a North-East town last evening was caught in the beams of searchlights and attacked by anti-aircraft fire. A short while afterwards, another raider was met by gunfire.

Soon afterwards, five bombs were heard.”

But other snippets from the paper build up a picture of life in wartime.

One report began: “With fixed bayonets, British troops ran through the main street of a North-East coastal town yesterday. They turned off to comb byways while Bren Gun carriers roared on their tractors towards the sea. Shoppers ran for cover and civilians peered from doorways as the crash of rifle fire was heard.”

The headline gave the game away: “Ready for invasion: realistic rehearsals.”

The story expressed the mood of the North-East, where reports of the indiscriminate nature of the Germans’ bombing of London were fuelling flames of public outrage.

“It is an undoubted fact that everywhere in Northern Command there’s a new deep and bitter feeling against the enemy as a result of what’s happening nightly in and around the Metropolis,”

said the Echo.

It was reported that Middlesbrough Council had provided air raid shelter provision for 115,424 people, mostly in Anderson shelters in back gardens and lanes. When private shelters were counted, every one of the town’s 140,000 people could find a place of safety.

In Hartlepool, there was debate about whether all the town’s youngsters should be evacuated. Only the coastal strip was designated an evacuation zone, with 174 youngsters registered, so inland parents were sending children away at their own expense.

The paper reported that, because of the number of nighttime air raids, the start of the schoolday was to be put back to 10am so pupils could catch up on their kip.

And then there were the Spitfire Funds. Darlington’s had grown by another £100 following an ARP sale of work at Claremont in Trinity Road, and Hartlepool’s Hurricane Fund had reached £300.

Bishop Auckland was launching its Spitfire Fund with Lord Barnard as president and Sybil Lady Eden president of the women’s committee. The opening donation was £240 – does anyone know if it reached its £5,000 target?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here