100 years ago an awesome new fighting machine made its mark as thousands of men died during the horrific Battle of the Somme

“CONSTERNATION spread among the Germans when these sinister, flat-footed monsters advanced, spouting flames from every side and careless alike of rifle and machine gun fire,” said the Northern Despatch newspaper 100 years ago this weekend. “They went right up to and over barbed wire entanglements, crushing everything before them, seeking out hidden machineguns and silencing them.”

This was the start of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, on the Somme, which was the first time “a tank” had been deployed on a First World War battlefield.

And the Durham Light Infantry was in the very thickest of the terrible fighting of this historic battle. In fact last week – September 16, 1916 – was one of the bloodiest days in the regiment’s history. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website, 405 members of the DLI died in that 24-hour period.

Powered by the tank - “an enormous steel monster from which spurted a continuous fire of great violence" – the battle raged for eight days around the French villages of Flers and Courcelette, across what The Northern Echo described as “seven miles of murdered countryside – dismantled woods, dis-housed villages, disembowelled fields”.

By September 22, when the fighting died down a little, 762 Durhams had been killed.

Many of their bodies were never recovered, and so only their names could be remembered on the giant memorial at Thiepval. For instance, of the 28 men from Darlington who died in the battle, 21 of them have no known grave.

Death was indiscriminate. On the database of Darlington men on The Northern Echo’s North-East at War website, Private Arthur Peart is listed beside Lieutenant Ronald Pease. Both died on September 15, but what different lives they had lived up until that day. Pte Peart, 29, was a Co-op grocer and the son of a North Road railwayman who lived in a terraced house in Wales Street; Lt Pease, 19, was the son of the Darlington MP, the Rt Hon Herbert Pike Pease, who had grown up in the mansion of Hummersknott and who had gone to the front straight from Eton.

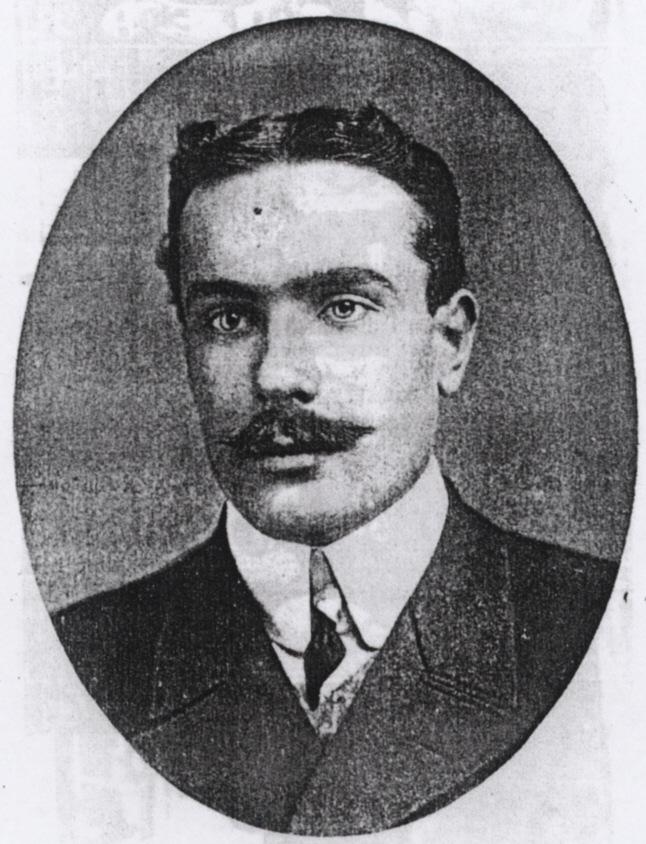

Also killed on September 15 at Flers-Courcelette was Captain Thomas Rowlandson, 36, of Newton Morrell, near Barton. Before the war, he had played in goal for Newcastle and Sunderland, and he had toured the world with Corinthian FC playing the beautiful game in a gentlemanly way. He’d joined the Yorkshire Regiment at Northallerton, and died in the first tank battle leading his men over the top armed, his obituary in The Northern Echo said, only with a walking stick. Extraordinary.

The bombardment ahead of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette had begun on the German lines on September 12, and the battle exploded into life shortly after 9am, when the British soldiers emerged from their trenches and advanced under the shadow of a “creeping barrage” – the heavy guns behind them bombarded the ground in front of them but kept moving forward, allowing them to progress.

But the barrage wasn’t heavy enough and the Germans were well dug in.

Six regiments of the DLI were on the north bank of the Somme. Their task was to advance from Flers towards the village of Gueudecourt, about two miles away, which the Germans had protected with a seemingly impenetrable network of steel-lined trenches – The Northern Echo of 1916 called it the “Wunder Werk”; the soldiers probably knew it as “the Quadrilateral” because of its shape.

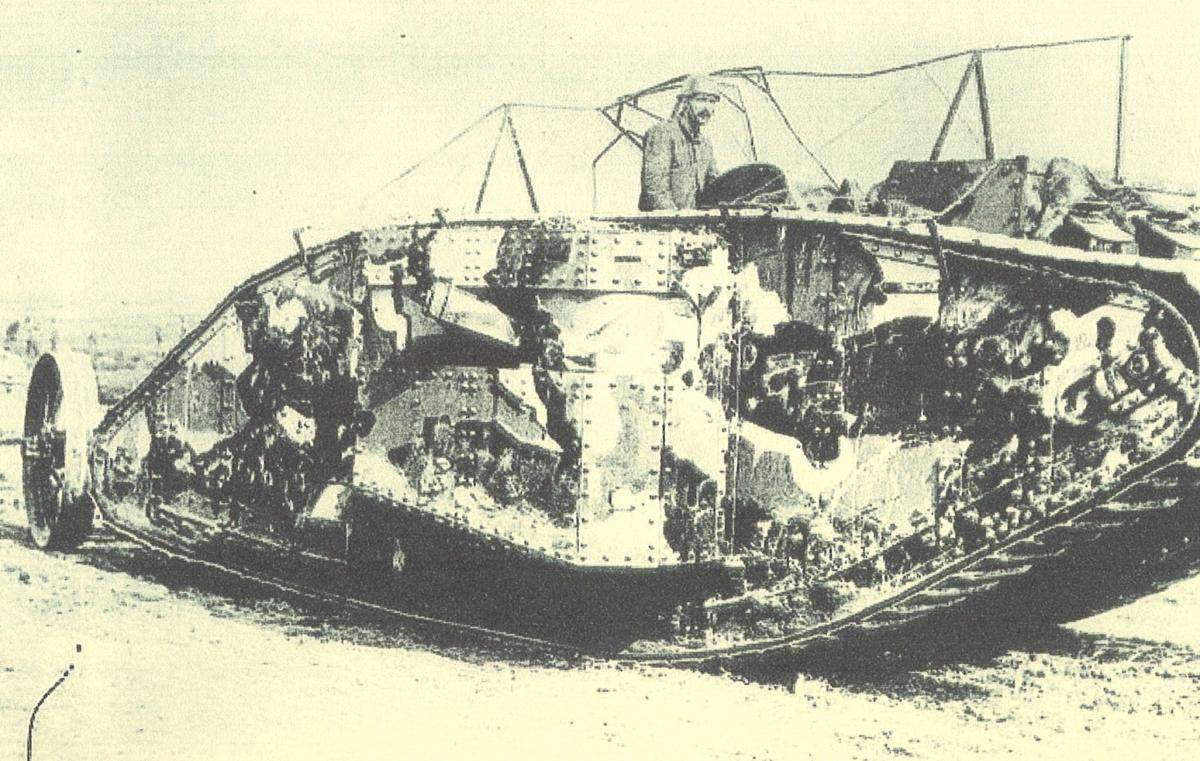

They were to be supported by “the tanks”. No one knew what to call them in September 1916. “New type of armoured car employed”, was The Northern Echo’s headline, and it also referred to them as “mobile turrets”.

“They looked like blind creatures emerging from the primeval slime,” said the paper’s special correspondent, who obviously knew his Lewis Carroll. “To watch one crawling around a battered wood in the half light was to think of ‘the Jabberwock with eyes of flame’.”

The British had 49 tanks, which were championed by Winston Churchill. But in those early days, they were desperately unreliable. On September 15, only 15 made it to the battlefield, where seven failed to start.

Those that did get going certainly had an impact on the enemy. Machine gun fire, which could scythe down a whole battalion of humans, just bounced off the reinforced sides of the tank with a puff of blue smoke – the Echo’s colourful correspondent said the vehicle shook “off from its pachyderm the petty insults of the German bombers”.

But there weren’t enough tanks to go round. Most soldiers had to face the enemy with rifles, or just walking sticks, if they were really unlucky.

The 10th and the 15th battalions of the DLI were cruelly treated, each losing about 400 men on September 16. By dusk, the 15th were back where they had started, and the 10th were lost – Sergeant J Donnelly was sent to check which regiment was on their flank, but when he shouted: “Are you the Somersets?”, he was shot in the arm by a German.

The regimental diary says: “Success was beyond the power of the very best troops.”

The 14th arrived that evening in the darkness, and found their trenches full of dead and wounded soldiers from the Norfolk and Suffolk regiments. They cleared them out and spent September 17 (a quiet day, as the DLI only suffered 53 fatalities) repairing their trenches ready for the next push which was due at dawn on September 18.

But at midnight, the Germans sent over a surprise heavy bombardment, as if they were planning to counter-attack. The 14th dropped their shovels and picked up their guns, but the counter-attack never came.

At 5.50am on September 19, in the pouring rain, the 14th belatedly launched their own attack, by which time they had already lost 24 men – one of whom was Private Fred Vitty, from Fir Tree, near Bishop Auckland (see separate article).

And so it was all along the muddy kilometres between Flers and Courcelette. The British advancing painfully slowly and sporadically, occasionally supported by "the tanks" and sometimes undone by their own side. For instance, on September 19, the 13th DLI captured 130 yards of trench near Flers and erected a barricade to keep the Germans out. But then, by mistake, British artillery bombarded the Durhams’ barricade for four hours, preventing them from pushing home their advantage.

In the official histories, the Battle of Flers-Courcelette grinds to a halt on September 22, with the surviving British soldiers so tired that they fell asleep in the mud where they stood. In reality, localised fighting could flare up at any moment for days afterwards.

At dawn on September 26, the 350 survivors of the 15th and 20th battalions of the DLI got their hands on a tank, fired it up and sent it spurting bullets towards the fortified Quadrilateral trenches. Supported by a low-flying aeroplane, the Durhams over-ran at the Quadrilateral at about 9am and captured 400 Germans frightened by the sight of the sinister, flat-footed monster.

The Durhams kept on going into Gueudecourt, making good progress until the tank ran out of petrol.

So the British did achieve some of their objectives at Flers-Courcelette and they did gain ground. But even with all their spurting tanks and all of their spilled blood, they did not win a decisive victory.

Indeed, all they had done was run up against another series of enemy strongholds which would have to be taken in another battle on another day with another heavy loss of life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here