AN explosion of extraordinary force tore through the narrow, dark, dusty channels deep in the bowels of County Durham 120 years ago. Everything in its path was destroyed.

“Huge balks of timber were splintered to matchwood, coal trucks were smashed to atoms and even the couplings snapped, while great falls of roof were apparent,” said The Northern Echo’s reporter who peered down the shaft of Brancepeth Colliery, near the pit village of Willington.

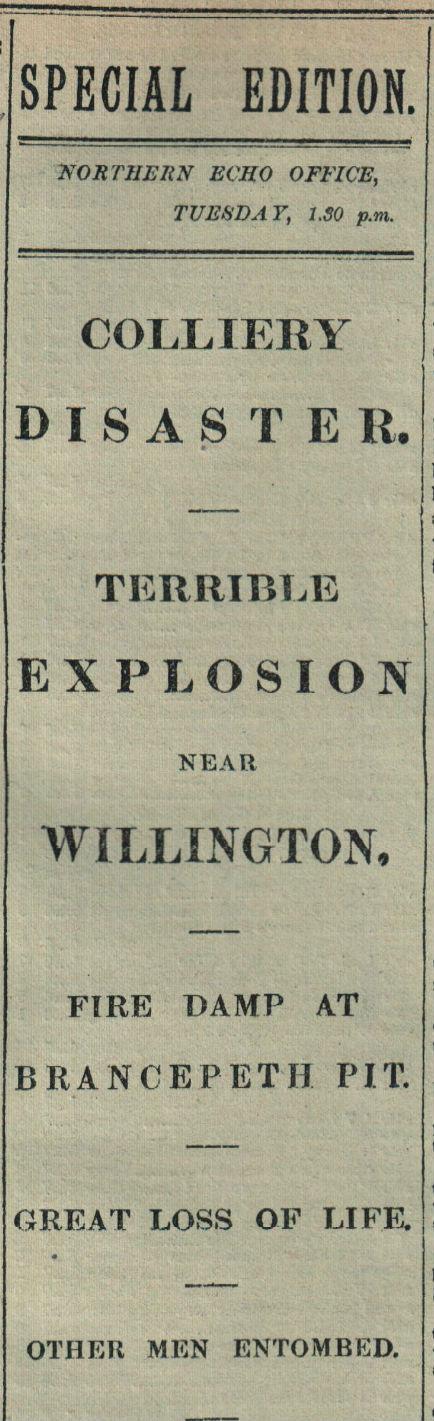

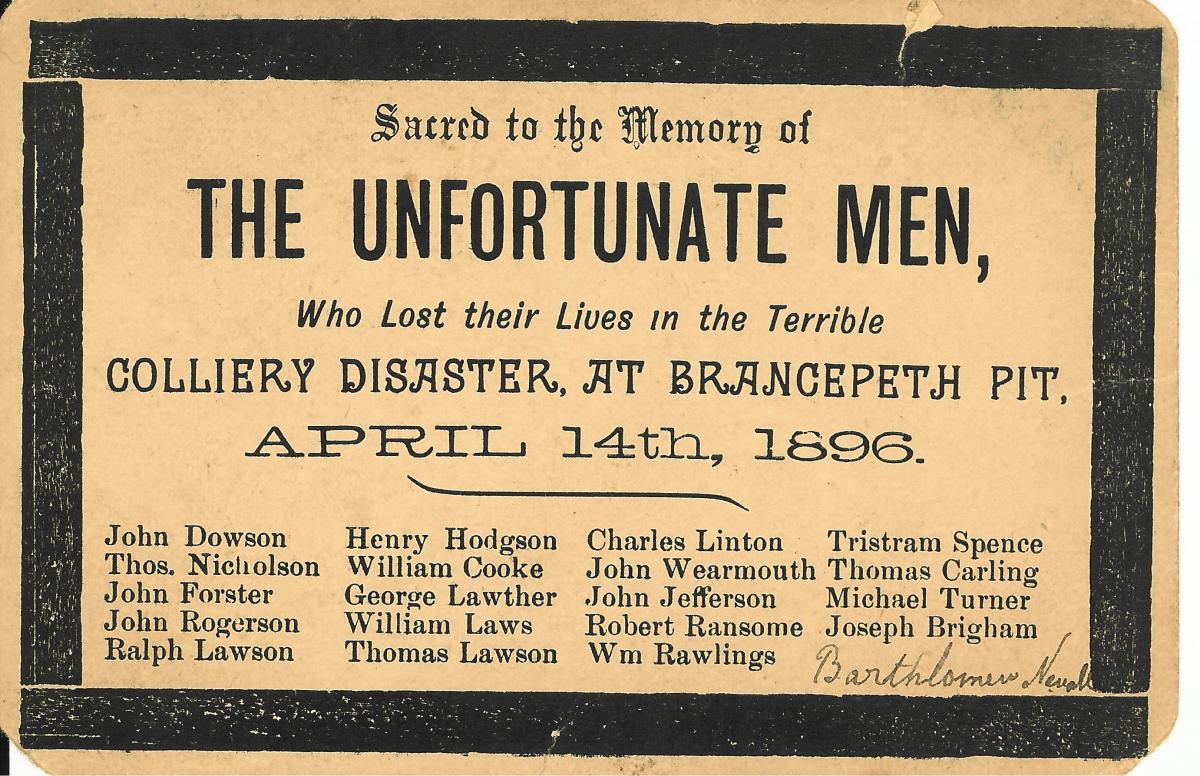

Against such forces, the human body stood no chance. Twenty men and boys were killed in the explosion on Monday, April 13, 1896.

One, who bore the brunt of the blast, was literally blown to bits; a couple more were scorched skinless by the fireball, and several others were crushed almost formless by the rockfalls. The rest were poisoned by the carbon monoxide, the “afterdamp”, which silently spread in the wake of the explosion. They were found “stark and rigid in the gloomy galleries of death”, physically untouched – a couple had handkerchiefs still stuffed in their mouths in a forlorn attempt to keep the gas out; one still had his bait spread out on his knee.

All 20 were remembered on a marble plaque paid for by the Brancepeth Colliery Literary Society and unveiled the following year by the colliery owner, Joseph Straker. For a couple of decades the memorial was in the colliery offices but from 1928, it took pride of place in the newly opened Miners Welfare Hall.

However, the hall has been boarded up and derelict for at least ten years – even the wildly bumpy BMX track which covers the perfectly flat lawns where the miners once played bowls is overgrown by weeds. Last month, though, the plaque was rescued after protracted discussions from the dereliction and it has now safely arrived in Beamish museum, where it will be installed in the band hall (the unveiling is pencilled in for April 1 next year).

Brancepeth Colliery was sunk in 1840, and grew into one of the biggest in the county, employing more than 2,000 men for most of the 20th Century. When it closed in 1967, the Echo reckoned that just ten years earlier it had been at the centre of a combine of interconnected collieries which together employed 16,650 men.

When the disaster took place in 1896, there were more than 1,500 men working in its three pits. The explosion occurred at 10pm in the Brockwell seam of Pit A about three miles from the shaft bottom. Fortunately, at that time of night, there were only a few score men down below, doing maintenance and preparatory work; if it had occurred between the hours of 4am and 4pm, there would have been 300 or more potential victims down there.

Within hours, brave rescue teams were pouring down the stricken shaft trying to reach their entombed colleagues. “Stalwart, self-possessed miners, carrying their lamps and in willing groups, took turns of riding down the shaft, their singular costume conveying a touching picture of the Durham miners’ devotion to duty in the hour of dire danger,” said the Echo.

Several of the would-be rescuers were themselves overcome by afterdamp and had to be carried out unconscious.

Among the teams was the Mid Durham MP, John Wilson, a pitman turned parliamentarian. He ventured deeper than most until his way was blocked by a rockfall which had killed two miners. “One of them was wedged under the fall but I had to feel whether it was a man or not,” he told the Echo as he emerged from the pithead. “I found a man’s leg and then we observed that the body was wedged in among the stone. His mate was over on the other side of the fall. The blood was oozing out of his eyes and mouth and his short was torn and his skin burned.”

It was a day of huge drama, as the inconsolable womenfolk, shrieking loudly, gathered at the pithead hoping against hope that their man had somehow escaped. Crowds started arriving by the thousand by train – “Willington presented the appearance usual to a gala or flower show day” – to witness the drama. The railway rushed in an extra ticket inspector; the police sent in reinforcements from Durham and Bishop Auckland to control the rubber-neckers who, the Echo said, behaved respectfully.

The first bodies came up at 5.30pm on Tuesday, April 14 – “voiceless corpses in pit flannels”, said the Echo, sparing few details. Their arrival was greeted by the sound of hammering and sawing coming from the colliery joiner’s shop as the carpenters created the coffins.

Among the first up was that of Joseph Foster – “minus head, arms and legs” – who had borne the brunt of the blast.

“Only a nameless and indescribable wreck of poor Foster could be descried from the outline of the canvas in which his remains were wrapped,” said the Echo. “His remains were enough to leave a ghastly memory on all permitted to see them.”

He was only been identified because he had been wearing a new, homemade, white shirt for the first time that shift – a piece of it was removed, washed and compared to the offcuts still in his house.

The inquests into how the men died began on Wednesday, April 15 – before the last of the bodies had been recovered.

“The first body inspected by the jury was that of Thomas Moses Nicholson, which was lying at the home of his parents in Catherine Street,” said the Echo’s reporter. “It was lying in the front room – an exceptionally clean, tidy and well furnished apartment – and was in a polished pitch pine coffin underneath the window.

“Up to the neck, and covering the chin and mouth, the remains were swathed in spotless white cotton, with a small bow of black ribbon fixed at the throat.

“The face, of course, was exposed to view, and though cleared of the grime of the pit, showed over nearly the whole surface the effects of the explosion. With the exception of a small portion of the cheeks and forehead, the skin had peeled off with the heat of the flame, and presented the appearance of raw flesh.”

Nicholson, 20, had been studying firedamp in a bid to further his career in the colliery when he was killed. His wife gave birth to their first son on Saturday, April 18.

The reporter continued: “Leaving the Nicholsons’ abode, the jury made their way to the precincts of the pit where, just as they arrived, a piteous scene was witnessed. Ralph Lawson’s remains had just been identified by his widow, who was just leaving in terrible distress, her grief being quite uncontrollable.”

Lawson, 60, was a respected deputy who left a grown-up family. He was on the brink of early retirement due to his declining health.

Every one of the 20 victims had a little back story.

Michael Turner, 50, left a widow “with but one arm”, said the Echo, and ten children and another on the way. Charles Lintern, 34, had become a father for the sixth time the day before the explosion. George Lawther (who was also known as Rutherford) left a widow and five children.

Thomas Lawson, 65, was killed. His daughter was married to the son of William Cook, 52, who was the one the MP had found crushed by the rockfall, and his son was married to the daughter of William Rawlings, 50, who was found dead with a handkerchief in his mouth – Rawlings’ son, Joseph, had been killed by a stonefall in the pit 15 months earlier.

Tristram Spence’s father, Wilson, had also been killed in a stonefall down Brancepeth four years earlier, and his grandfather and uncle had died in the 1880 Seaham pit disaster. Tristram, 31, had been so taken by his father’s funeral that he had asked that, should he ever suffer the same fate, the Willington brass band should also play at his funeral. And so it did.

And the mother of the youngest victim, Thomas Carling, just 14, had asked him not to go to work that fateful shift as his intended brother-in-law was seriously unwell. The brother-in-law died the night of the explosion and so the two were buried in the same grave.

The first funerals were held on Thursday, April 16. “The corteges, each headed by a hearse and several conveyances, extended over half a mile, and almost every house showed drawn blinds,” said the Echo. “Over a thousand persons walked behind the hearses.”

And so the living quickly had to come to terms with their loss – the parents with the loss of their sons, the widows with the loss of their breadwinners, the children and even the unborn babies with the loss of their fathers.

That is why the memorial plaque was so important to Willington and why it is so good that it has been rescued from the derelict welfare to go on permanent display at Beamish.

AN inquiry into the disaster concluded a month later that someone – probably the extremely experienced mastershifter, John Rogerson, 66 – had fired a shot of gunpowder. It could have been deliberate to bring down some stone, although a powder canister was found near the seat of the explosion which could have been fired accidentally.

The inquiry concluded that the shot had ignited the coal dust in the atmosphere which caused the explosion which, it said, “culminated in the deaths of 20 men and boys accidentally”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here