Teesside's most famous sporting son fought against the odds to compete in the Olympic Games but, in the end, his career was a casualty of war.

Chris Lloyd tells the second part of the story of the Tees Valley's greatest Olympian, Jack Hatfield, who also set records in the Big Swim.

IN 1912, Jack Hatfield won three Olympic medals. In 1913, he won the English Championship. In 1914, war broke out, and the Olympian found himself in the trenches of the Somme, wading through mud rather than swimming through water.

The Middlesbrough Olympian joined the Royal Artillery and served as a saddler – possibly because, as the proprietor of a sports shop, he had experience with leather goods. He and his brothers-inarms were, his son Jack Jr says, “like dogs, living in slime”.

But at least he survived. His elder brother, Tom, was killed on the Somme in 1916.

The privations of the front were not good preparations for resuming a world class swimming career in peacetime.

“In 1919, he camped out at Ormesby and every night, after a day’s working in the shop, he went training in the Cleveland Hills,” says Jack Jr, who lives in a retirement home in Middleton St George.

The shop had opened in 1912 – it celebrates its 100th anniversary in August – and one of its early successful lines was the daring cotton costume, without arms and legs, to which Jack attributed his Olympic success.

But full-time shopkeeping was also not a good preparation for a world class swimming career.

In the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, Jack fell short. In the heats of the 400m and 1,500m he came third, swimming more than a minute slower than he had eight years earlier, and he failed to qualify for even the semi-finals.

Over the next few years, he continued to work hard, and he continued to win English championships. He was selected for the 1924 Olympics in Paris – and did really well.

He reached the final of the 1,500m, swimming 30 seconds faster than he had in 1912.

Yet times had moved on: he finished fourth in the final, seven seconds outside the bronze position.

He reached the final of the 400m too, but The Northern Echo was not hopeful. “Hatfield,”

it said, “though not so good as he once was, swam exceedingly well in the semifinal, and as the fastest loser, qualified for the final. He will not win, but he may be in excellent form and run very near to the great Australian and American cracks.”

It was right. He came fifth – nearly 30 seconds behind the legendary American “crack”, Johnny Weissmuller who set an Olympic record.

In 1928, Jack, now 35, was selected for his fourth Olympics, this time in Amsterdam.

He came second in his 400m heat, but rather than pursue a solo medal, he opted to play in a water polo match.

The Echo reported: “Hatfield did not take part in the semi-final... He was a member of the British team which was beaten by France by seven goals to one, Britain’s only goal coming from the Middlesbrough man.”

That was the end of a remarkable Olympic career that spanned 16 years, but Jack had one last major tournament in him: the 1930 inaugural Empire Games in Canada.

“He didn’t get placed in any of his events,” says his son, “but he carried the flag for the English team and that was his swansong.”

Jack, though, was still big box office. Thousands watched him train on Teesside and, in the days when amateur sportsmen were great celebrities, he was the swimmer that organisers wanted at their galas across the country.

He became the English Five Mile Champion in a race held in the River Thames. It was such an amazing endurance event that Teesside organised its own version and called it The Northern Echo Big Swim.

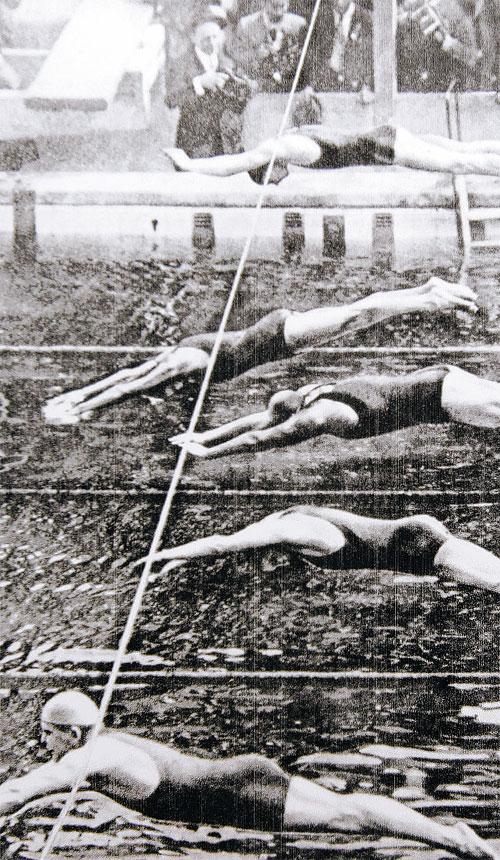

Competitors dived from a barge beside the Victoria Bridge at Stockton and splashed five miles and 387 yards to the Transporter Bridge at Middlesbrough.

The inaugural Big Swim was on July 7, 1930. It was controversial because detractors thought there would be deaths through exhaustion.

Perhaps it was that fatal fascination that drew the crowd: the Echo guesstimated that 50,000 crammed the riverbanks to see the 16 hardy souls swim past.

“On the wharves all the way to the Transporter Bridge were black masses of people,”

reported the paper. “High upon furnace tops they could be seen taking a breather to see the swim go by. Cranemen leaned out of their cabins to wave on the competitors, and from the various craft lying at anchor came much delighted applause.”

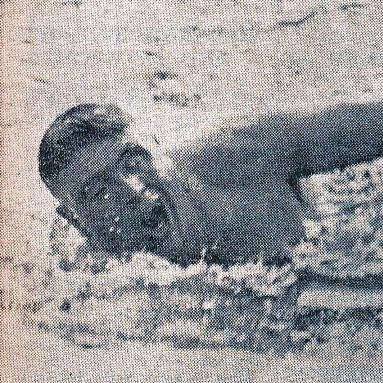

Of course, no one died. And, of course, Jack Hatfield won.

He finished in one hour and 24 minutes and 57 seconds – five minutes, and quarter of a mile, ahead of his nearest rival, E Johnson of Stockton.

“‘Is that Hatfield?’ asked one grimy ironworker who had left his furnace to look after itself for a moment or two. ‘Yes’ went back the reply.

‘Good old Jack,’ returned the sporting shout.” Or so the Echo reported.

Jack won the Big Swim again in 1931, missed 1932 and 1933, but showed up in 1934 and, of course, won.

“He had a busy day at his sports outfitting shop almost to the time of the swim,” said the Echo. “He rushed away to Stockton, did the course, and was back again in his store lending a hand within a very short time.”

Among the tens of thousands of spectators that year was Jack’s new wife and his new son, who was named after him. “My mother always told me that she put me in a baby carriage and took me to Newport Bridge so I could watch him swim underneath,”

says Jack Jr.

The 1934 Tees Big Swim was one of 41-year-old Jack Sr’s last major trophies. He devoted more time to his iconic shop, which is now one of the Boro’s longest trading businesses, and from 1952, he was a director of Middlesbrough Football Club.

He died in 1965. An obituary described him as “possibly the most popular man on Teesside”. He was quite probably the Tees Valley’s greatest sporting son: as well as the three Olympic medals and the four Olympic Games, he won 42 English championships, set four world records and three English records, was the centre forward of England’s water polo team for 12 years and was installed in the Swimming Hall of Fame in Fort Lauderdale in 1984.

All that, yet the First World War robbed him of his finest years.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here